The Jewish Community of Leer

Leer

A town in the district of Leer in Lower Saxony, Germany.

First Jewish presence: 1611; peak Jewish population: 306 in 1885; Jewish population in 1933: unknown

In 1925, 289 Jews lived in Leer, making the community the third-largest in East Friesland. Leer was home to a Jewish cemetery by the middle of the 17th century. The last burial conducted there before the Shoah took place on June 11, 1939. A Jewish school was established on Kirchstrasse at some point between 1840 and 1850; later, during the first decade of the 20th century, the community opened a new school—the building housed an apartment for a teacher—on Deichstrasse (present-day 14 Ubbo-Emmius-Strasse). The synagogue on Heisfelder Strasse was inaugurated in 1885.

On Pogrom Night (Nov. 9, 1938), SA men set the synagogue on fire. Jews from Leer and the surrounding areas were assembled at the fairgrounds; the women and children were later released, but the men were sent (via Oldenburg) to Sachsenhausen, where they were interned until the end of December 1938 (possibly January 1939). In late January 1940, local Jews were ordered to leave East Friesland by April 1, 1940. By then, Jewish properties had been confiscated, and Jews had been forcibly moved into the ghetto located at the corner of Groninger and Kampstrasse. The Jewish school was closed on February 23, 1940, and the ghetto was liquidated on October 23, 1941. In March 1943, the municipality bought the Jewish cemetery, after which, in May of that same year, Dutch slave laborers were forced to remove the gravestones from the oldest section of the Jewish cemetery. Approximately 20 to 30 Leer Jews survived the war. Miriam Hermann, one of the survivors, was deported to Theresienstadt Nazi concentration camp on February 10, 1945. Almost 90% of the community perished in the Shoah. After the war, a stone tablet bearing the ten commandments— it had once stood above the synagogue door—was found in a neighboring vegetable garden; in 1984, the tablet was transferred to the Ichud-Shviat-Tzion synagogue on Ben Yehuda Street in Tel Aviv. During the years 1946 to 1985, six Jews were buried in the oldest part of the Jewish cemetery, which was returned to the Jewish community in 1953. Memorial plaques were unveiled at the former synagogue site (on September 12, 1961) and at the cemetery.

------------------------------------------------------

This entry was originally published on Beit Ashkenaz - Destroyed German Synagogues and Communities website and contributed to the Database of the Museum of the Jewish People courtesy of Beit Ashkenaz.

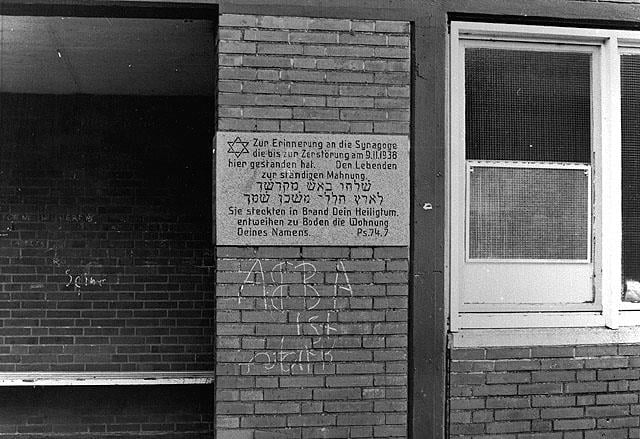

Memorial plaque for the synagogue destroyed during Kristallnacht in Leer, Germany, 1980's

(Photos)in Leer, a small town near Emden, Germany, 1980s

The synagogue was destroyed on Kristallnacht

(November 9-10, 1938). The plaque was installed

on the new building built on the site of the old synagogue

(The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot,

courtesy of Yehiel Hirschberg, Israel)

Three buildings which served as the Jewish Ghetto, Leer, Germany, c1980

(Photos)in th esmall town of Leer, Germany, September c1980

It is where the Jews of Leer were held at the beginning of World War II

(The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot,

courtesy of Yehiel Hirshberg, Israel)

The synagogue in Leer near Emden, Germany, 1920's

(Photos)on the Dutch border, Germany, 1920's

The synagogue was destroyed on Kristallnacht

(November 9-10, 1938)

(The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot,

courtesy of Yehiel Hirschberg, Israel)

Theresienstadt - Terezin

(Place)The fortress of Terezin (in German Theresienstadt) in north-west Czechoslovakia was founded during the reign of Kaiser Joseph II and named after his mother, Maria-Theresa. In 1941, the Nazis decided to concentrate in Terezin most of the Jews of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, including the elderly, prominent personalities and those with special privileges, and gradually to transport them from there to the death camps. They transformed the town into a ghetto, and between November 24, 1941 and April 20, 1945 some 140,000 Jews were brought there. In September 1942, the ghetto population reached a peak of 53,000. Of the Jews who passed through the ghetto, approximately 33,000 died there, while 80,000 were transported from there to the extermination camps. In the fall of 1944 only 11,000 Jews were left alive in Terezin.

Most of the inmates of Terezin were assimilated Jews, many of them artists, writers and scholars, who helped to organize intensive cultural activities: orchestras, an opera group, theater, light entertainment and cabaret. The Germans had established the ghetto with the aim of misleading world public opinion regarding the extermination of European Jewry, by presenting Terezin as a model Jewish settlement.

Emden

(Place)Emden

A city in Lower Saxony, Germany.

Emden is a seaport, and located on the Ems River.

HISTORY

Legend has it that Jews arrived in Emden during antiquity, both as exiles after the destruction of the First Temple, and as slaves accompanying the Roman legions after the destruction of the Second Temple. The first historical reference to Jews in Emden dates from the second half of the 16th century; David b. Shlomoh Gans mentions the Jews of Emden in his book Tzemach David.

In 1590 the non-Jewish citizens of Emden complained to the emperor’s local representative that the Jews were permitted to follow their religious precepts openly and were exempt from wearing the Jewish badge.

Marranos from Portugal passed through Emden on their way to Amsterdam; a few settled in Emden and returned to practicing Judaism. Moses Uri HaLevy (1594-1620), a rabbi in Emden, ultimately left to settle in Amsterdam along with the Spanish-Portuguese Marranos, where he served as the first chakham of the Portuguese community. Emden’s city council distinguished between the local Jews and the Portuguese, encouraging the latter to settle in the city, while attempting to expel the former. Their attempts, however, were unsuccessful, after the intervention of the duke in their favor. The judicial rights of the Portuguese Jews were defined in a grant of privilege issued by the city council in 1649,

and renewed in 1703.

In 1744, when Emden was annexed to Prussia, the Jews came under Prussian law. After this point, the Jews of Emden would go through cycles of gaining and losing rights. In 1762 anti-Jewish riots broke out in Emden. Then, in 1808, during the rule of Louis Bonaparte, the Jews in Emden were granted equal civil rights. However, these rights were abolished under Hanoverian rule in 1815, and the Jews of Emden were not emancipated until 1842.

A new synagogue was built in 1836; it was later expanded in 1910 to include a mikvah (ritual bath) and additional seating. A Jewish school was established in 1845, and a Talmud Torah was founded in 1896.

Noted rabbis of Emden included Jacob Emden (1728-1733), and Samson Raphael Hirsch (1841-1847).

In 1808 there were 500 Jews living in Emden. The community numbered 900 in 1905, and 1,000 in 1930.

THE HOLOCAUST

Many of Emden’s Jews left after the Nazi rise to power. In 1933 the community numbered 581, which decreased to 298 in 1939.

The synagogue was burned down during the Kristallnacht pogrom (November 9-10. 1938).

During World War II (1939-1945) most of the Jews remaining in Emden were deported. 110 Jews were deported from Emden to Lodz.

POSTWAR

There were six Jews living in Emden in 1967.

Papenburg an der Ems

(Place)Papenburg an der Ems

A city in the district of Emsland in Lower Saxony, Germany, situated at the river Ems.

First Jewish presence: 1771; peak Jewish population: 127 in 1890; Jewish population in 1933: 71

In 1863, after the synagogue in nearby Aschendorf ceased to function, the Jews of Papenburg an der Ems petitioned for their own synagogue. On May 12, 1887, one was inaugurated at 51 Hauptkanal; behind the new house of worship, in an older building, the community built a school and an apartment for a teacher. Papenburg’s mikveh, which was located in the Hes family home at 42 Hauptkanal, was renovated in 1921. We also know that the provincial rabbinate was in nearby Emden, and that from 1805 until 1937, burials were conducted in a cemetery two kilometers north of Aschendorf. In 1922, when only nine children attended the Jewish school, the authorities in Osnabrueck closed it down; the school was not reopened until 1937. On Pogrom Night (Nov. 9, 1938), SA men set the synagogue and school building on fire. Jewish-owned property was vandalized and looted, and the Hes family’s home and business were set on fire. Jewish men were arrested and sent, via Osnabrueck, to the Oranienburg concentration camp. On December 5, 1941, most of the remaining Jews (five families) were deported to Riga. The last were taken to Theresienstadt Nazi concentration camp on January 29, 1942. Alice Hes and the Polak sisters returned to Papenburg after the Shoah. Twenty-two of the 71 Jews who lived in Papenburg in 1933 perished in the Shoah. According to Yad Vashem, the death toll for Papenburg was approximately 60.

--------------------------------------------

This entry was originally published on Beit Ashkenaz - Destroyed German Synagogues and Communities website and contributed to the Database of the Museum of the Jewish People courtesy of Beit Ashkenaz.

Oldenburg

(Place)Oldenburg

A city in the state of Lower Saxony, Germany

The Jewish community of Oldenburg is heavily Russian, owing to the immigration that took place after the fall of the Soviet Union. Community institutions include a synagogue, and the Leo Trepp Beit Midrash (study house), which houses a Sunday school for Jewish students.

In spite of vandalism, both during the Kristallnacht pogrom and after World War II, many of the tombstones in Oldenburg’s Jewish cemetery have remained standing. The last burial that took place in the cemetery occurred in the year 2000, after which another cemetery was opened in the Bummerstede district, approximately 3 miles (5.5km) from the city center.

In 2013 there were 315 Jews living in Oldenburg, about the same number as were living in the city before World War II.

History

Jews were living in Oldenburg by the early 14th century and existed nearly continuously since then. In 1334 the municipal council decided to cease issuing letters of protection (Schutzbriefe) to Jews; nonetheless, Jews continued to live in Oldenburg under the protection of the Duke. Though the Duke of Oldenburg protected them, he also limited their economic activities to moneylending only.

During the period of the Black Plague (1348), the community ceased to exist, but was apparently restored after a short time.

Between 1667 and 1773 Oldenburg was ruled by Denmark. During this period the nobility enjoyed the services of Sephardi court Jews and financiers from Hamburg, including Jacob Mussaphia and his sons. The Goldschmidt family sold and traded meat in Oldenburg.

In 1807 there were 27 Jews living in Oldenburg (0.6% of the total population). It was during the 19th century that the Jews of Oldenburg, along with those across Europe, were emancipated and granted civil and legal rights. As a result, Jews saw their economic opportunities expand. The Jews of Oldenburg began working in textiles, as pharmacists, and in manufacturing, among other professions.

In 1827 the Jews were required to be called German names and to speak German.

In 1829 Rabbi Nathan Marcus Adler was appointed as the first local Chief Rabbi (Landrabbiner) of Oldenburg. He was succeeded by Bernhard Wechsler (d. 1874), who oversaw the consecration of a new synagogue in Oldenburg in 1835.

A number of Jews from Oldenburg and the surrounding area were killed in action during World War I (1914-1918). The local synagogue erected plaques to commemorate the fallen. A number of organizations were also established to aid members of the Jewish community in the wake of the war, including a Jewish welfare organization, and a Gemilut Chassadim organization. Other organizations that served Oldenburg’s population during the interwar period were the Israelite Women’s Association, and a branch of the Maccabi Youth sports club.

The Jews of the duchy numbered 1,359 in 1900; by 1925 their number had declined to 1,015 (of whom 250 lived in Oldenburg itself). Other communities existed in the towns of Delmenhorst, Jever, Varel, Vechta and Wildeshausen and in the region of Birkenfeld, Bosen, Hoppstaedten, Oberstein, Idar and Soetern.

The Holocaust

When the Nazis took power in 1933 there were 279 Jews living in Oldenberg. In the wake of the Nazi rise to power, many Jews in Oldenburg – and, indeed, throughout Germany – began emigrating.

On Kristallnacht, November 9-10, 1938, the synagogue was destroyed, along with the last two Jewish stores that had remained open. Most of the community's men, including the Landrabbiner Leo Trepp, were sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp for a few weeks. By 1939 there were only 96 Jews remaining in Oldenburg.

Postwar

Approximately 20 survivors returned to Oldenburg after the war and reestablished a Jewish community. A small prayer room was opened in 1948. Although the synagogue had been burned down during Kristallnacht, in 1949 and 1950 those responsible for the arson were tried and given prison sentences. However, the community declined, due mainly to emigration; by the end of the 1960's there were only four Jews living in Oldenburg, and the community itself was dissolved at the end of January 1971.

The Jewish community was revived, however, after the collapse of the USSR and the immigration of Jews from the Soviet Union to Germany. A new synagogue was opened in 1995, in a building that once housed a Baptist chapel. Rabbi Bea Wyler served as the community's rabbi during the late 1990's, the first female rabbi to serve a German congregation.

Aurich

(Place)Aurich

A town near the river Ems in the district of East Frisia, Lower Saxony, Germany.

Jews from Italy first settled in Aurich apparently around 1378 following an invitation from the ruler of the region. This community came to an end in the 15th century. In 1592 two Jews were permitted to perform as musicians in the villages around Aurich. A new community was formed by 1647 when the court Jew Samson Kalman ben Abraham settled there. He was the court Jew of the Earl of east Frisia. Aurich was the seat of the "Landparnass" and "Landrabbiner" of east Friesland from 1686 until 1813, when they were transferred to Emden.

A cemetery was opened in Aurich in 1764; the synagogue was consecrated in 1811. Under Dutch rule (1807-1815) the Jews enjoyed the civil rights which they had lost in 1744 under Prussian rule.

By 1744 ten families had settled in Aurich. Their number increased steadily and by the time Napoleon granted full political and civil rights to the Jews of east Frisia (1808), Aurich had 16 Jewish families, who in total numbered 180 inhabitants. Their number increased to 600 by the end of the 19th century, about 8% of the total population. Due to the move out of the rural settlements caused by the industrialization, the number of Jewish inhabitants of Aurich decreased at the beginning of the 20th century.

Most of the Jews of Aurich traded in cattle, farm products and textiles. Others were butchers. They had considerable influence on the economic life of the town, for example no market day was held on the Sabbath. In 1933, the year of the Nazis' rise to power in Germany, the Jewish community of Aurich numbered 400 persons.

The Holocaust Period

Numerous Jews from Aurich were able to emigrate during the first years of the Nazi regime. After the invasion of the Netherlands by Nazi Germany, the remaining Jews of east Frisia were deported in 1940, among them were 140 Jews from Aurich. The Jewish community ceased to exist.