קהילת יהודי ברית המועצות

1920 | מעצר באישון ליל

ביום רביעי, 14 ביולי 1927, נעצרה מכונית לפני בניין מס' 22 ברחוב מאחוויה בלנינגרד. מהמכונית יצאו שני גברתנים במעילי פרווה כבדים ובמגפי עור. השניים, סוכני המשטרה החשאית הסובייטית ג.פ.או, טיפסו בצעדים מהירים לאחת הקומות הגבוהות בבניין. פקודת המעצר שאחזו בידיהם חתמה תקופה ארוכה של תצפיות יומיומיות על אדם שהיה חשוד בפעילות אנטי-קומוניסטית. שמו היה רבי יוסף יצחק שניאורסון, ראש חסידות חב"ד העולמית.

הרב אמנם הצליח, לאחר תלאות ותפניות מסעירות, לחמוק מהמעצר ולהימלט מברית-המועצות, אולם סיפורו מגלם בצורה מזוקקת את המאבק על הזהות היהודית בברית-המועצות שבה שלטה ביד רמה המפלגה הקומוניסטית.

שבע שנים קודם לכן – בשנת 1920, שלוש שנים לאחר המהפכה הבולשביקית ("מהפכת אוקטובר") – נקבעו גבולותיה של רוסיה הסובייטית. המוני היהודים בתחום שליטתה של אמא רוסיה, כ-2.5 מיליון במספר, חשו רגשות מעורבים. מחד גיסא, רבים ממנהיגי המהפכה הבולשביקית היו יהודים (ובכללם ליאון טרוצקי, ממארגני הצבא האדום), האנטישמיות הרשמית בוטלה ויהודים הורשו להתגורר בכל רחבי ברית-המועצות. מאידך גיסא, השלטון החדש קבע כי כל מי שמשתתף בפעילות דתית או לאומית הוא "אויב הפרולטריון". כך הוצאו אל מחוץ לחוק תנועת הבונד והתנועה הציונית, הדיבור בעברית נאסר ובתי-הכנסת פונו והפכו למרכזי תרבות בשירות התעמולה הסובייטית.

ארגון יבסקציה, המחלקה היהודית של המפלגה הסובייטית, שרוב חבריו היו יהודים ופעילים נאמנים במפלגה הקומוניסטית, נועד למעשה כדי לדכא את הלאומיות היהודית ברוסיה. הארגון הוציא לאור עיתון, "דער עמעס" ("האמת"), שהציג תעמולה סובייטית ביידיש – השפה היחידה שהשלטון הקומוניסטי הכיר בה כשפה לאומית-יהודית. חברי המערכת לא בחלו באמצעים כדי להשיג את מבוקשם: מחיקת הזהות היהודית והשתלבות של העם היהודי בפרולטריון הבינלאומי.

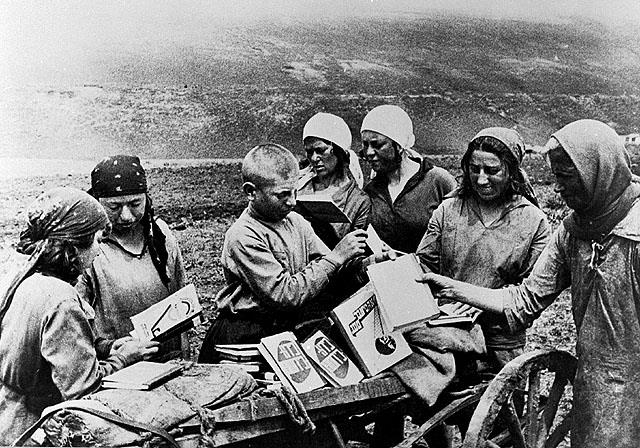

1926 | בני ההרים

הם דיברו בניב יהודי פרסי ובו מלים עבריות וארמיות, הקפידו על המסורת היהודית ועל הטקסים הדתיים ושימרו את מנהג הכנסת האורחים המפורסם שלהם על-פי כל כללי הטקס העתיקים. יהודי ההרים, הלוא הם בני יהדות בוכרה, גיאורגיה, קזחסטן ועוד, שכינו את עצמם "ג'והור" (יהודים), חיו בארצות הקווקז מאות שנים והיו חלק בלתי נפרד מיהדות ברית-המועצות שאחרי המהפכה.

יש שגרסו כי יהודי ההרים הם צאצאיו של שבט יהודה שגלו לבבל בשנת 586 לפנה"ס. אחרים טענו כי הם צאצאי עשרת השבטים שגלו מהארץ כ-140 שנה קודם לכן. כך או כך, ולמרות תקופות ארוכות שבהן חיו בניתוק מהקהילות היהודיות בעולם, הקפידו יהודי ההרים על חופה וקידושין, שחיטה כשרה, ברית מילה, חגים ומועדים.

הציונות במובנה המשיחי היתה מושרשת במורשתם מאז ומעולם, ובמרוצת הדורות עלו רבים מהם לירושלים, מי ברגל ומי ברכב, ואף נטמנו בהר הזיתים. הם תרמו ממון לישיבות בארץ הקודש, ושליחים מארץ-ישראל התקבלו בבתיהם בחמימות רבה.

בתחילה הסתייגו רבים מבני ההרים מן הציונות המודרנית, בעיקר בשל אופיה החילוני, אך עם השנים אימצו את ערכי הציונות בדרכם. הם שלחו נציגים לקונגרסים הציוניים, אספו כספים למטרות ציוניות, והעובדה שעסקו בעיקר בחקלאות עוררה את התפעלותו של בנימין זאב הרצל, שאמר עליהם כי "הם יהיו חלוצי עבודת האדמה בארץ-ישראל". בשנת 1926 הקימו עולים מבני העדה את היישוב כפר-ברוך ליד נהלל, וכעבור 50 שנה הצטרפו רבים מהנותרים בברית-המועצות לעלייה הגדולה של שנות ה-70.

1928 | עונת הציד האנטישמית

בשנות ה-20 של המאה ה-20 הנהיג ולדימיר איליץ' לנין, מנהיג רוסיה הסובייטית דאז, את "המדיניות הכלכלית החדשה" (NEP), שהתירה יזמות חופשית באופן חלקי. היהודים, שעיסוקם המרכזי היה מסחר זעיר-בורגני, נהנו בתחילה ממדיניות זו, אך המסים הגבוהים שגבה המשטר רוששו אותם ורבים מהם נאלצו לסגור את עסקיהם לטובת חקלאות ועבודה במינהל הציבורי.

במהלך השנים הללו הקימו יהודי ברית-המועצות רשת של בתי-ספר ביידיש, שבשיאה למדו בה 160 אלף תלמידים (כשליש מכלל התלמידים היהודים בברית-המועצות). עוד נוסדו תיאטראות שהציגו מחזות של מנדלי מוכר ספרים וי"ל פרץ, וכן "פקולטות לתרבות יהודית פרולטרית" באוניברסיטאות מינסק וקייב, שם לימדו יהדות בנוסח סטלין, כלומר, "לאומית בצורתה וסוציאליסטית בתוכנה".

בשנת 1928 הוצאה לפועל תוכנית החומש הכלכלית של סטלין, וברית-המועצות עוצבה סופית כדיקטטורה קומוניסטית. בתי-הספר היהודיים נסגרו, מעמד הסוחרים היהודים חוסל וספרות היידיש הלכה וגוועה (מבין 124 סופרים יהודים שהשתתפו בכנס הספרות הסובייטי שהתקיים ב-1934, רק 24 כתבו ביידיש). הפתרון הסובייטי ל"בעיה היהודית" היה הקמת "מחוז יהודי אוטונומי" באזור בירוביג'אן, אבל הניסיון לא צלח. לאזור היגרו רק 20 אלף יהודים, ו-11 אלף מהם עזבו בתוך זמן לא רב.

בשנת 1930 פתח המשטר בחיסול שיטתי של מוסדות יהודיים שהוא עצמו הקים. בשנים 1937–1938, בתקופת "הטיהורים הגדולים" של סטלין, נאסרו, הוגלו או הוצאו להורג אלפי יהודים. "עונת הציד האנטישמית", כפי שהיא מכונה במחקר, הסתיימה רק בשנת 1953, עם מותו של הרודן.

התפלגות המקצועות היהודיים בברית-המועצות, 1926

עיסוק %

פקידים 40.6

פועלים 30.6

בעלי מלאכה מאוגדים 16.1

בעלי מלאכה עצמאיים 4.0

איכרים בקולחוז 5.8

אחרים 2.9

1941 | שואת הכדורים

באוגוסט 1939 נחתם בין ברית-המועצות לגרמניה הנאצית הסכם ריבנטוב-מולוטוב. במסגרת ההסכם סיפחה ברית-המועצות את הארצות הבלטיות – ליטא, לטביה ואסטוניה – מחוזות בסרביה וברומניה, וכן חלקים מפולין. בעקבות זאת הצטרפו למניין יהודי ברית-המועצות יותר מ-2 מיליון נפש.

וכך, ב-22 ביוני 1941, ערב פלישת הגרמנים לברית-המועצות (מבצע ברברוסה), חיו בה כ-5 מיליון יהודים. הגרמנים, שהשמדת היהודים היתה מבחינתם אחד מיעדי המלחמה, הקצו למטרה זו את פלוגות ה"איינזצגרופן" הרצחניות. בניגוד למכונת הרצח השיטתית שהופעלה במחנות ההשמדה, פלוגות אלו נקטו אמצעים "רגילים": הן פשוט רצחו ביריות את רוב יהודי הארצות הבלטיות, בלארוס ואוקראינה. מיד לאחר כיבוש כפר, עיר או עיירה, נהגו הגרמנים למנות יודנראט (מוסד שהיה ממונה על תיווך בין השלטון הנאצי ליהודים המקומיים), וכל יהודי המקום נצטוו להירשם במשרדיו. כעבור כמה ימים קיבלו היהודים הוראה להתכנס בנקודה מסוימת, שם נאמר להם כי הם נוסעים לפלשתינה. עד מהרה התברר להם כי הדרך לפלשתינה עוברת בבורות הירי של באבי-יאר ופונאר. שיטה אחרת היתה הקמת גטאות שתושביהם הועסקו בעבודות כפייה ונרצחו לאחר כמה שבועות או חודשים, גם הם בבורות הירי.

כ-1.5 מיליון איש נרצחו בשואת יהודי ברית-המועצות, שכונתה גם "שואת הכדורים". ניצלו אלה אשר פונו בידי השלטונות או התגוררו באזורים שהגרמנים לא הגיעו אליהם.

יש לציין כי במהלך המלחמה מאות אלפי יהודים התגייסו לשורות הצבא האדום, וכ-161 אלף מהם אף זכו באותות הצטיינות

1953 | משפט הרופאים

בכ"ט בנובמבר 1947 הצביע האו"ם בעד הקמת מדינה יהודית. להצבעה קדמו נאומים חוצבי להבות שנשאו נציגי אומות העולם. אחד מהם, נציג רוסיה הסובייטית, אנדריי גרומיקו, דיבר בפרץ של רגשה על זכותו של העם היהודי המעונה והנרדף לקרן זווית משלו בארץ אבותיו, ארץ ישראל.

ואולם, רק תמימים התייחסו ברצינות לאהבת היהודים שהפגין הנציג הסובייטי. הקול היה אמנם קולו של גרומיקו, אבל הידיים שהניעו את הבובה היו ידיו של "שמש העמים", המנהיג יוסף סטלין.

במהלך מלחמת העולם השנייה ביקש השלטון הסובייטי להטמיע את היהודים במנגנון הקומוניסטי וגילה אפס סובלנות כלפי כל ביטוי של דתיות או של לאומיות יהודית. לאחר הקמתה של מדינת ישראל, מדיניות זו הוחרפה עד כדי כך שהשנים 1948–1953 מכונות במחקר ההיסטורי "התקופה השחורה של היהדות הסובייטית".

בינואר 1948 נרצח בתאונת דרכים מבוימת הבמאי והפעיל החברתי היהודי שלמה מיכואלס, בהוראתו הסודית של סטלין. לאחר ארבע שנים, באוגוסט 1952, הוצאו להורג 13 חברי הוועד האנטי-פשיסטי היהודי. ב-1953 התחוללה "עלילת הרופאים", שבמסגרתה הואשמה קבוצת רופאים יהודים מהקרמלין בניסיון להרעיל את מנהיגי המפלגה והצבא; בשנת 1953 מת סטלין, וכחודש לאחר מותו התברר כי ההאשמה שהופנתה כלפי הרופאים היתה מופרכת. היה זה רק פרט אחד בשורה של גילויים על מעשיו הנוראים של המנהיג, ונאומו המפורסם של מחליפו חרושצ'וב על אודות הפשעים שביצע "מורו ורבו" בישר על הקלה מסוימת גם ביחס ליהודים. אחד מביטוייה של ההקלה הזו היה האישור שקיבל בית-הכנסת הגדול במוסקבה להוציא לאור סידור תפילות ולפתוח ישיבה קטנה. הדבר היה בשנת 1957, ובית-הכנסת הפך למוקד לאומי ליהודים דתיים וחילונים כאחד.

1970 | "החתונה" של אסירי ציון

נצחונה של ישראל על צבאות ערב במלחמת ששת הימים ב-1967 עורר את תחושת הגאווה הלאומית של יהודי ברית-המועצות. "האזרחים הסובייטים בני הלאום היהודי", כתב הסופר היהודי אלי ויזל, "הפכו מיהודי דממה ליהודי תקווה".

ואכן, בשנים שלאחר המלחמה החלו קבוצות ציוניות מחתרתיות לפעול במלוא העוז נגד מדיניות הדיכוי הסובייטית, שהגבילה את אישורי העלייה לארץ ישראל. הפעולות היו מגוונות: שיגור אלפי מכתבים אישיים וקבוצתיים לאנשי ציבור משפיעים במערב, הרחבת פעילותה של הסָאמִיזְדָאט (הוצאה לאור מחתרתית שהעתיקה יצירות ספרותיות מערביות ועיתונים אסורים והפיצה אותם בסתר), חוגי בית שבהם נפגשו פעילים ציונים ועוד. הפעילים שנאסרו כונו "אסירי ציון", ומאחר שבחוק הסובייטי לא היה איסור מפורש על פעילות ציונית, הם הואשמו ב"תעמולה אנטי-סובייטית".

ב-15 ביוני 1970 נעצרה קבוצה של פעילים יהודים בשדה התעופה של לנינגרד. חברי הקבוצה נתפסו בעיצומו של מבצע הרפתקני שנשא את שם הקוד "החתונה". מטרת המבצע היתה להשתלט על מטוס נוסעים בלנינגרד, להטיס אותו לשבדיה ומשם לארץ ישראל. מתכנני המבצע נידונו למוות בירייה, אך בעקבות לחץ בינלאומי הומתק עונשם למאסר של 13–15 שנה.

מבצע "חתונה" אמנם נכשל, אבל הקרב על התודעה הבינלאומית עלה בהצלחה. ברית-המועצות נכנעה ללחץ העולמי, ורבים מהפונים קיבלו אשרות עלייה לישראל. לא כולם: אסירת ציון אידה נודל, מסורבת עלייה ידועה, תלתה על מרפסת דירתה את הכרזה "קג"ב – החזר את הוויזה לישראל", וכתוצאה מכך נידונה לארבע שנות גלות בסיביר.

שנה מספר אשרות עלייה לישראל

1970 3,000

1971 12,900

1972 31,900

1980 | קפקא במשרדי האוביר

בראשית שנות ה-1980, בשיאה של המלחמה הקרה ובעיצומה של הפלישה הסובייטית לאפגניסטן, תמה תקופת ה"ריכוך" ביחסים בין מזרח ומערב. כל מי שפנה למשרדי האוביר, שהיו אחראים על הנפקת היתרי יציאה מברית-המועצות, למד על בשרו את משמעותה הקפקאית של הדיקטטורה הביורוקרטית הסובייטית. הפקידים סירבו להעניק היתרי יציאה באמתלות שונות ומשונות, החל ב"פגיעה באינטרסים של המדינה" וכלה בסירוב שרירותי, ללא כל מידע על מועד פקיעתו.

רוב הסירובניקים של שנות ה-1980 המתינו עד תשע שנים להיתר עלייה. העריצות הפקידותית הביאה לשורה של תופעות חברתיות קשות. רבים ממסורבי העלייה מצאו את עצמם חסרי עבודה, סולקו מהאוניברסיטאות ואולצו להתגייס לצבא. משהשתחררו גילו שאינם רשאים לעזוב את ברית-המועצות. הפעם נתלה הסירוב בתירוץ שלפיו התוודעו לסודות צבאיים. רבים מהם חשו מבודדים חברתית; ידידיהם ומכריהם התרחקו מהם מחשש שיאבדו גם הם את מקומות עבודתם. משפחות רבות התפרקו כשאחד מבני הזוג האשים את האחר שנסיונו לעלות לישראל מביא חורבן על הבית. במקרים מעטים אף הלשינו מסורבים לשלטונות על מכריהם בניסיון לזכות בהיתר המיוחל.

במקביל המשיכו לפעול בחשאי סמינרים ביתיים שעסקו בהיסטוריה יהודית, תערוכות של אמנים יהודים הוצגו בסתר, הוקמו ספריות מחתרתיות והוראת השפה העברית הלכה והתפשטה. בתחילת שנות ה-1980 פעלו במוסקבה כ-100 מורים לעברית.

אחד הביטויים המרשימים לפעילות מחתרתית זו היה אירוע שהתקיים בקרחת יער גדולה, כשלושה ק"מ מתחנת אובראז'קי המוסקבאית. שם, הרחק מעיני "האח הגדול", נערכו שיעורים ביהדות ובהיסטוריה יהודית, תחרויות של שירים יהודיים, ציוני חגים יהודיים, משחקים ופיקניקים. שיאו של הנוהג היה במאי 1980, אז הגיעו לאובראז'קי יותר מ-1,000 איש, אולם אז הטיל הקג"ב מצור על המקום ולא איפשר את גישת היהודים אליו.

1989 | קומוניזם רות סוף

במרץ 1987 הפגינו שבעה מסורבי עלייה ליד ארמון סמולני בלנינגרד. להפתעת המפגינים, במקום לספוג מכות והשפלות, הם הוזמנו לדיון במרכז המפלגה. יתר על כן, תצלום של ההפגנה פורסם בעיתון ערב בלנינגרד, דבר שמעולם לא קרה קודם לכן. מה חולל את השינוי ביחסו של המשטר הקומוניסטי ליהודים?

בשנת 1985 עלה לשלטון בברית-המועצות מיכאיל גורבצ'וב והגה את מדיניות הפרסטרויקה ("בנייה מחדש") – רפורמה כלכלית-פוליטית המושתתת על ערכים מערביים ליברליים. השינוי לא היה מיידי. בראשית שלטונו של גורבצ'וב אמנם נמשכו מעצרים של פעילים ציונים, אך כעבור שנתיים החלו רוחות חדשות לנשב גם ברחוב היהודי.

בשנים 1987–1989 שוחררו רוב אסירי ציון ממאסרם, ובשלהי 1989 תמה ההמתנה מורטת העצבים של אחרוני מסורבי העלייה. השלטונות חדלו לרדוף את האולפנים להוראת העברית, בעיר טאלין יצא לאור עיתון יהודי עצמאי ראשון, "שחר", המדינה התירה רישום של קהילות וארגוני תרבות יהודיים, ובדצמבר 1989 התקיימה במוסקבה האסיפה המייסדת של "הוועד" – הארגון הראשי של כל הארגונים והקהילות היהודיות בברית-המועצות.

התפוררות המשטר הקומוניסטי ונפילת ברית-המועצות ב-1991 הובילו לעלייה המונית של עולים לישראל. העולה המיליון הגיע לארץ בשנת 2000 וסימל את סיום שנות "העלייה הגדולה".

רבים מעולי חבר-העמים חוו וחווים עדיין חבלי עלייה קשים, אולם רובם נקלטו בישראל בהצלחה רבה.

רוסיה

(מקום)1772 | היום פולני. מחר רוסי

לרבים נדמה כי ברוסיה חיו יהודים מאז ומעולם, אבל האמת היא שלמעט סוחרים יהודים בודדים שנדדו בין ירידים ברחבי האימפריה עד 1772 לא התגוררו בה יהודים כלל.

הסיבות לכך היו בעיקרן דתיות. בעוד שבחלקי אירופה האחרים ביקשה הכנסייה הקתולית לשמר את הישות היהודית במצב נחות כעדות לניצחון הנצרות על היהדות– הממסד הדתי המרכזי ברוסיה, הלוא הוא הכנסייה הפרבוסלבית, התנגד נחרצות ליישוב יהודים, שנתפסו כאחראים לצליבתו של ישו. עדות לאידאולוגיה זו אפשר למצוא באמרתה הנודעת של הקיסרית יליזבטה פטרובנה: "אין אני רוצה להפיק תועלת משונאיו של ישו".

מצב עניינים זה שרר עד השנים 1772–1795, שבמהלכן סיפחה האימפריה הרוסית חלקים גדולים מפולין בה חיו המוני שלומי בית ישראל. או אז החליטה הצארית יקטרינה השנייה, בעיקר מסיבות כלכליות, לשמר את הזכויות שהיהודים נהנו מהן תחת ממלכת פולין. כך מצאו עצמם מאות אלפי יהודים פולנים חיים תחת ריבונות רוסיה, וזאת בלי שזזו ממקומם אפילו סנטימטר אחד.

יקטרינה הבטיחה "שוויון זכויות לכל הנתינים, ללא הבדל לאום ודת", וליהודים העניקה ב-1785 את "כתב הזכויות לערים", שקבע כי ערי האימפריה ינוהלו על-ידי גופי ממשל אוטונומיים, והיהודים יוכלו ליהנות מהזכות להצביע למוסדות הללו בבחירות ולעבוד בהם. כמו כן נהנו היהודים מסובלנות דתית ומחופש תנועה יחסי בתוך "תחום המושב" – חבל הארץ המערבי של האימפריה הרוסית, שרק בו הותר ליהודים להתגורר.

1797 | גאון, בווילנה כבר היית?

אחד הפרקים המרתקים ביותר בתולדות יהדות רוסיה נוגע לאתוס הלמדנות של יהודי ליטא, וזאת למרות העובדה שרבים מיהודים הליטאים שכונו "ליטבקים" התגוררו בשטחים שנמצאים היום מחוץ לגבולה של ליטא המודרנית.

הכינוי "ליטבקים" התייחס בעיקר לזהות הרוחנית שאפיינה את היהודים הללו, וקידשה למדנות, רציונליות והתנגדות עזה לתנועה החסידית, שהלכה והתפשטה במזרח אירופה באותן שנים.

האתוס של הלמדן, תלמיד הישיבה השקוע יומם וליל בהוויות אביי ורבא ומקדיש את חייו לפלפולי התלמוד, היה מודל לחיקוי והתגלמות כוחו היוצר של המפגש בין אמונה לתבונה. יתרה מכך, תלמיד חכם שנמנה עם הליטבקים הפך לחלק מהאליטה של הקהילה, מעמד שפתח בפניו אפשרויות שידוך עם בנות עשירים ומיוחסים ובכך הבטיח את קיומו החומרי לכל חייו.

האב המייסד של המסורת הליטאית הלמדנית היה הגר"א, רבי אליהו בן-שלמה זלמן מווילנה, הידוע בכינויו הגאון מווילנה (1720–1779).

אף שלא נשא בכל משרה רשמית ונחשף לציבור לעתים נדירות בלבד, נהנה הגר"א מהערצה יוצאת דופן עוד בחייו. סמכותו נבעה בעיקר מכוח אישיותו והישגיו האינטלקטואליים. הגר"א העמיד תלמידים לרוב. המפורסם שבהם היה רב חיים מוולוז'ין, שייסד את ישיבת וולוז'ין הידועה. לימים ילמד בה המשורר הלאומי, חיים נחמן ביאליק.

1801 | אין ייאוש בעולם כלל

מול הדגם האליטיסטי של הלמדן הליטאי הרציונליסט עמד הדגם החסידי העממי, שהתמקד בחיי הרגש ובחוויה הדתית ודיבר אל לבם של יהודים עובדי כפיים וקשי יום.

המאבק בין שני הזרמים, שנודע כפולמוס בין החסידים למתנגדים, היה רצוף חרמות, נידויים והלשנות וידוע סיפורו של מייסד חסידות חב"ד, רבי שלמה זלמן מלאדי, שנאסר בכלא הרוסי בשנת 1801 בעקבות הלשנה של מתנגדים.

באזור "תחום המושב" פעלו כמה שושלות חסידות מפורסמות, ביניהן חסידות צ'רנוביל, חסידות סלונים, חסידות ברסלב, חסידות גור וכמובן חסידות חב"ד. בראש כל חצר חסידית עמד אדמו"ר – אדם אפוף מסתורין ומוקף הילת קדושה. לאדמו"ר יוחסו יכולות מאגיות וערוץ תקשורת ישיר עם ישויות גבוהות. המוני חסידים נהרו אליו בכל עניין – מבעיות פריון ועד מצוקות פרנסה ושידוכים.

לחסידים היו (ויש עדיין) קוד לבוש וסדרים חברתיים ייחודיים. הם נהגו להתאסף ב"שטיבל", ששימש בית-כנסת, בית-מדרש ומקום התכנסות לסעודות בשבתות וחגים. מדי פעם בפעם נהג החסיד לנסוע לחצר האדמו"ר, גם אם שכנה אלפי קילומטרים ממקום מגוריו. שיא הביקור היה סעודת ה"טיש" (שולחן, ביידיש), שנערכה בליל שבת ובמהלכה נהגו החסידים להתקבץ סביב האדמו"ר ולהיסחף לשירה אקסטטית שעוררה אותם להתעלות רוחנית.

על-פי תפיסת החסידות, השמחה היא מקור שורשה של הנשמה. השקפה זו באה לידי ביטוי באמרתו הנודעת של רבי נחמן מברסלב, "אין ייאוש בעולם כלל". עקרונות מרכזיים נוספים בחסידות הם אהבת האחר, ביטול המעמדות והסרת המחיצות. הערכים ההומניים הללו מתגלמים להפליא בתפילה שחיבר האדמו"ר רבי אלימלך מליז'ענסק:

"אדרבה, תן בלבנו שנראה כל אחד מעלות חברינו ולא חסרונם, ושנדבר כל אחד את חברו בדרך הישר והרצוי לפניך, ואל יעלה בלבנו שום שנאה מאחד על חברו חלילה ותחזק אותנו באהבה אליך, כאשר גלוי וידוע לפניך שיהא הכל נחת רוח אליך, אמן כן יהי רצון".

1804 | לתקן את היהודי

שלוש עשרה שנה אחרי שיהודי צרפת זכו לשוויון זכויות, חוקקו ברוסיה "תקנות 1804", שמטרתן המוצהרת הייתה "תיקונם של היהודים" ושילובם במרקם הכלכלי והחברתי של האימפריה הצארית.

כמו במקרים אחרים רבים בהיסטוריה היהודית, העיסוק ב"תיקון מצב היהודים" לווה בהצדקות טהרניות ובהתנשאות דתית שנועדו להכשיר את היחס השלילי כלפיהם. התקנות אמנם שיקפו את הגישה הליברלית של שלטונו המוקדם של הצאר אלכסנדר הראשון והתירו ליהודים ללמוד בכל מוסד רוסי, אולם בד בבד נדרשו היהודים "לטהר את דתם מן הקנאות והדעות הקדומות המזיקות כל-כך לאושרם", וזאת משום ש"תחת שום שלטון [היהודי] לא הגיע להשכלה הראויה, ואף שמר עד עתה על עצלות אסייתית לצד חוסר ניקיון מבחיל". יחד עם זאת נכתב בהמלצות ל"תקנות" כי טבעם של היהודים נובע מאי-ודאות בנוגע לפרנסתם, שבעטיה הם נאלצים "להסכים למלא כל דרישה, אם רק ימצאו בכך טובת הנאה כלשהי לעצמם".

חרף העובדה ש"תקנות 1804" היו נגועות באנטישמיות, בסופו של דבר הן היטיבו עם היהודים: "תחום המושב" הוגדר והורחב ונכללו בו אזורים חדשים, יהודים שבחרו לעסוק בחקלאות זכו לקרקעות ולהטבות מס, ובעלי הון יהודים שהקימו בתי-מלאכה קיבלו הזמנות עבודה מטעם המדינה.

1844 | השטעטל- העיירה היהודית

במשך מאות שנים הייתה השטעטל – העיירה היהודית במזרח אירופה – מעין מיקרוקוסמוס יהודי אוטונומי סגור. היידיש הייתה השפה השלטת, ומוסדות הקהילה – הגמ"ח, ההקדש, בתי-הדין וועד הקהילה – ניהלו את החיים הציבוריים. דמויות כמו הגבאי, השמש, השוחט אכלסו את סמטאותיה לצד שוטה הכפר, העגונה והבטלן של בית-המדרש. הקשר היחיד בין היהודים לתושבי האזור הגויים התנהל בירידים האזוריים ובשוק של יום ראשון, שנערך לרוב בכיכר המרכזית של העיירה.

חדירת ההשכלה והמודרניזם לשטעטל במהלך המאה ה-19 כרסמה במבנה המסורתי של העיירה. צעירים יהודים רבים ניתקו עצמם מן הבית, המשפחה והסביבה המוכרת. כמה מהם, ובכלל זה אברהם מאפו, ש"י אברמוביץ (בעל שם העט "מנדלי מוכר ספרים") ושלום עליכם, היו לימים חלוצי ספרות ההשכלה. בתיאוריהם, שנעו בין נוסטלגיה לסאטירה נוקבת, הם ציירו את העיירה היהודית על טיפוסיה, רחובותיה ומוסדותיה. לעתים הצליפו בעיירה ולעתים צבעו אותה בצבעים רומנטיים ונוסטלגיים.

מבנה העיירה המסורתי הותקף לא רק מבפנים, אלא גם מבחוץ. בשנת 1827 הוציא הצאר ניקולאי הראשון צו שהטיל על כל קהילה יהודית לספק מכסה מסוימת של צעירים בני 12–25 לצבא הרוסי לתקופה של 25 שנה. כשהקהילה לא עמדה במכסה, נשלחו שליחים מטעם הצאר שארבו לילדים וחטפו אותם מבית הוריהם וממקומות לימודיהם. הילדים נשלחו ליישובים מרוחקים, שם נמסרו לחינוך מחדש בבתי איכרים גויים עד שהגיעו לגיל צבא. "גזירת הקנטוניסטים", כפי שכונה הצו של הצאר, פילגה את הקהילה, שנאלצה להכריע שוב ושוב על אילו ילדים ייגזר הגורל המר.

בשנת 1835 קידם שלטון הצאר חוקים שגזרו על היהודים לבוש מיוחד, מנעו מהם להפיץ ספרים "מזיקים" ביידיש ובעברית וחילקו אותם ל"יהודים מועילים" ו-"ליהודים בלתי מועילים". מסמר נוסף בארון הקבורה של העיירה ננעץ בשנת 1844, אז בוטלה "שיטת הקהל", שהייתה מנגנון הניהול העצמי של הקהילה היהודית במשך שנים רבות.

1860 | אודסה- עיר ללא הפסקה

מן המפורסמות היא ששפה מייצרת תודעה ותודעה מייצרת מציאות. דוגמה לכך היא מדיניותו של אלכסנדר השני, שבניגוד לאביו ניקולאי, שבחר להעניש "יהודים רעים", הוא ביקש "לתגמל יהודים טובים".

היהודים הסתערו על הרפורמות של אלכסנדר כמוצאי שלל רב. דמויות כמו א"י רוטשטיין, הקוסם הפיננסי הגדול, משפחת פוליאקוב, שרישתה את אדמות האימפריה במסילות ברזל, והברון יוסף גינצבורג, שייסד רשת בנקים מסועפת בכל רוסיה, הן כמה דוגמאות בולטות ליהודים שניצלו בכישרון רב את מדיניותו הליברלית של אלכסנדר השני.

אווירת הליברליות התפשטה גם לעולם הדפוס כשעיתונים יהודיים צמחו כפטריות אחרי הגשם, וביניהם "המגיד" (1856), "המליץ" (1860) ו"הכרמל" (1860

מאמצע המאה-19 הפכה העיר אודסה, ששכנה על גדות הים השחור, למרכז השכלה וספרות יהודי. בעיר הקוסמופוליטית פעלו סוחרים יוונים לצד מוזגים טורקים ואינטלקטואלים רוסים, אלו התענגו על אווירת החופש והמתירנות של אודסה, עליה נאמר בהלצה כי "הגיהינום בוער מאה פרסאות סביב לה".

השילוב בין חדשנות, בינלאומיות והווי חיים נטול משקעי עבר הפך את העיר לאבן שואבת ליהודים, שזרמו אליה מכל חלקי תחום המושב – אוקראינה, רוסיה הלבנה, ליטא ועוד. כדי לסבר את האוזן: בשנת 1841 חיו באודסה 8,000 יהודים בלבד, אך בשנת 1873 כבר הגיע מספרם לכ-51,837.

בשנות ה-60 של המאה ה-19 התקבצו באודסה משכילים רבים, ביניהם פרץ סמולנסקין, אלכסנדר צדרבוים, ישראל אקסנפלד וי"י לרנר. שנים אחר-כך פעלו בה אישים משפיעים אחרים, וביניהם מנדלי מוכר-ספרים, אחד-העם וחיים נחמן ביאליק. באודסה הם יכלו לקיים אורח חיים פתוח, להחליף דעות באופן חופשי, לעלות לרגל אל חצרו של סופר נערץ ולהתבדר בצוותא בלי לחוש אשמה על שהם מבטלים זמן לימוד תורה.

באותה תקופה החלו יהודים, לרוב עשירים, להתיישב גם מחוץ לתחום המושב – במוסקבה ובסנט-פטרבורג. זאת, נוסף לקהילה יהודית קטנה שחיה במרכז רוסיה, בארצות הקווקז.

1881 | שמן בגלגלי המהפכה

תקוות היהודים להשתלב בחברה הרוסית ולהיות, כמאמר המשורר היהודי הנערץ יהודה לייב גורדון, "אדם בצאתך ויהודי באוהליך", התרסקה על צוק האנטישמיות המודרנית, שהרימה את ראשה המכוער בשנת 1880.

מסנוורים מהרפורמות של הצאר אלכסנדר השני ומההשתלבות המואצת בחיי הכלכלה, התרבות והאקדמיה, התעלמו היהודים מהסיקורים האנטישמיים שהלכו ורווחו בעיתונות ובספרות הרוסיות שתיארו בעקביות את "מזימתם" להשתלט על רוסיה ולנשל את האיכר הפשוט מאדמתו.

הסופר פיודור מיכאלוביץ' רשטניקוב, למשל, תיאר בכתביו כיצד יהודים קונים צעירים וצעירות רוסים ומתעמרים בהם כמו היו עבדים. החרה החזיק אחריו דוסטוייבסקי שביצירת המופת שלו "האחים קראמזוב" מתאר יהודי שצולב ילד בן ארבע אל הקיר ומתענג על גסיסתו. תיאורים אלה ואחרים חלחלו אל המון העם והאיכרים, שחיפשו אשמים בכישלונם להתחרות בשוק החופשי שנוצר לאחר ביטול מוסד הצמיתות בשנת 1861.

פרעות 1881, שכונו "סופות בנגב", הותירו את היהודים מוכי צער ותדהמה. אכזבה רבה נבעה

לנוכח שתיקתה של האינטליגנציה הרוסית, שבמקרה הטוב סכרה את פיה, במקרה הרע עודדה את הפורעים, ובמקרה הציני התייחסה ליהודים כאל "שמן בגלגלי המהפכה", תיאור שהיה נפוץ בקרב מהפכנים סוציאליסטים רוסים. תגובות אלו חידדו אצל היהודים את ההכרה המייאשת בכך שבין אם יצטרפו לכוחות הלאומיים המקומיים, יתבוללו או יאמצו ערכים סוציאליסטים – לעולם ייחשבו לזרים לא-רצויים ויזכו ליחס חשדני ואלים.

1884 | לך לך מארצך וממולדתך

קביעתו של ניטשה כי "התקווה היא הרעה שברעות, משום שהיא מאריכה את קיומו של הסבל" אמנם נושאת מסר פסימי, אך אין מדויקת ממנה לתיאור מצב היהודים במהלך שנות ה-80 של המאה ה-19.

פרעות "סופות בנגב" שפרצו ב-1881 והאקלים האנטישמי שאף התחזק בעקבותיהן עם חקיקת "חוקי מאי" וחוק ה"נומרוס קלאוזוס" (הגבלת מכסת הסטודנטים היהודים באוניברסיטאות) הובילו את היהודים להבנה כי ההמתנה לאמנציפציה (שוויון זכויות) רק תאריך את סבלם.

משנת 1881 ועד פרוץ מלחמת העולם הראשונה ב-1914 עזבו את תחום המושב ברוסיה כשני מיליון יהודים, רובם לאמריקה ומקצתם לארגנטינה, בריטניה, דרום-אפריקה, אוסטרליה וארץ ישראל.

מיתוס אמריקה כ"די גולדענע מדינה" (ארץ הזהב, ביידיש) הילך קסם על המהגרים. המציאות היתה רומנטית קצת פחות. בהגיעם לאמריקה הצטופפו המהגרים בשכונות קטנות וסבלו מעוני ומתנאי תברואה קשים, מציאות שהשתפרה רק כעבור דור אחד או שניים.

בד בבד הובילה האנטישמיות ברוסיה לתחיית הלאומיות היהודית, שבאה לידי ביטוי בייסוד תנועת חיבת-ציון ב-1884 בעיר קטוביץ'. אחד מהאישים שהתוו את הקו האידאולוגי של התנועה היה יהודה לייב פינסקר, מחבר המניפסט "אוטו-אמנסיפציה" (שחרור עצמי).

כדי לתאר את היחסים בין היהודים לחברה הכללית השתמש פינסקר בדימוי "האוהב הדחוי": כמו אוהב שמחזר אחר אהובתו ונדחה שוב ושוב, כך היהודי מנסה ללא הרף לזכות באהבתו של הרוסי, אך ללא הצלחה. הפתרון היחיד, אליבא דפינסקר, היה לייסד מסגרת מדינית לאומית בארץ אבותינו, ארץ ישראל.

במחקר ההיסטורי מקובלת ההנחה כי חיבת-ציון נכשלה כתנועה, אולם הצליחה כרעיון. ואכן, העלייה הראשונה לארץ ישראל, שהתארגנה במסגרת התנועה, הייתה הסנונית שבישרה את בוא העליות הבאות.

1897 | יהודי כל העולם התאחדו

לתאריכים יש לפעמים חיים משלהם. כך למשל בחר שר ההיסטוריה בשנת 1897 כתאריך הרשמי שבו נולדו רשמית שני זרמים יהודיים מקבילים ומשפיעים ביותר בתקופה המודרנית: התנועה הציונית העולמית ותנועת הבונד, הלוא היא מפלגת הפועלים של יהודי רוסיה.

בעוד שהקונגרס הציוני הראשון התכנס באולם הקזינו הנוצץ שבבאזל, הבונד נוסדה, כיאה לתנועת פועלים, בעליית גג בפרבר של העיר וילנה.

מפלגת הבונד ינקה את האידיאולוגיה שלה ממקורות מרקסיסטיים-סוציאליסטיים, וכפועל יוצא מכך סלדה מבורגנות, מדתות וממבנים חברתיים היררכיים. המפלגה קראה לבטל את כל החגים ולהותיר רק את ה-1 במאי, החג שבו, על-פי מנהיגי המפלגה, "ירעדו ויפחדו הבורגנים המרושעים בעלי העיניים הגאוותניות והחמסניות". הבונד התנגדה לציונות וקראה ליהודים לכונן "הסתדרות סוציאל-דמוקרטית של הפרולטריון היהודי, שאינה מוגבלת בפעולתה בשום תחומים אזוריים".

אין להבין מכך כי אנשי הבונד התנכרו לזהותם היהודית. ההפך הוא הנכון: תנועת הבונד חינכה את חבריה לכבוד עצמי, לאי-השלמה עם הפוגרומים ולתגובה אקטיבית על מעשי קיפוח ועוול. צעירי התנועה אף קראו לאחיהם היהודים לקחת את גורלם בידיהם.

באקלים הסוציאליסטי שהלך והתפשט במזרח אירופה בימים ההם זכתה הבונד להצלחה מרובה, אך במבחן ההיסטוריה דווקא התנועה המקבילה, הציונות, היא שטרפה את הקלפים.

1903 | אין עוד מלבדנו

בשנה שבה התפרסמו ברוסיה "הפרוטוקולים של זקני ציון" – אולי המסמך האנטישמי הנפוץ ביותר בעולם עד היום – נשלח בחור צעיר לסקר את הפרעות שפרצו בעיר קישינב, שכונו לימים "פוגרום קישינב". הזוועות שנחשפו לנגד עיניו של האיש, המשורר חיים נחמן ביאליק, התגלגלו בעטו המושחזת לאחד השירים המטלטלים ביותר בשירה העברית, "בעיר ההריגה". שיר זה נחשב לכתב תוכחה חריף נגד החברה היהודית, והוא פצע את נפשם של רבים מן הקוראים. חרפת היהודים, שהסתתרו בחוריהם והתפללו שהרעה לא תבוא אליהם, כשלנגד עיניהם נאנסות ונרצחות אמותיהם, נשותיהם ובנותיהם, נחשפה בשיר במלים ברורות וקשות.

מילותיו של ביאליק חדרו עמוק, ועוררו ברבים מיהודי רוסיה רגשות נקם וצורך עז לעשות מעשה ולא לחכות במחבוא עד לבוא המרצחים. רבים מקרב היהודים הפנימו את ההכרה כי יהודי חייב להגן על עצמו, ולא – אבוד יאבד.

הייתה זו מהפכה הכרתית של ממש. היהודים, שהיו רגילים למעמד של מיעוט הנצרך להגנתו של אחר, נאלצו לגדל אגרופים תודעתיים יש מאין. שיריהם של ביאליק וכתביו של ברדיצ'בסקי אמנם עוררו בהם סערת רגש, אך הרתיעה מאלימות הייתה טבועה בעומק התודעה הקולקטיבית שלהם. רובם נטו אחר הלך הרוח המתון והמאופק של אחד-העם יותר מאשר אחר זה של חיים ברנר הסוער והשש אלי קרב.

ועדיין, היסטוריונים רבים מסמנים את פוגרום קישינב כקו פרשת המים; רגע מכונן שבו התחולל המעבר מהתדר הנפשי של "אין עוד מלבדו" לזה של "אין עוד מלבדנו".

1917 | האינטרנציונל העולמי

עם תום מלחמת העולם הראשונה, שבמהלכה נהרגו רבבות חיילים יהודים על מזבח אימא רוסיה, החל עידן חדש בתולדות ארץ הפטיש והמגל לעתיד לבוא. המונופול על הכוח, שהיה נתון בידי בית רומאנוב האגדי, התגלגל אל העם. השוויון היה לערך עליון, והפועל הפשוט כבר לא היה (כביכול) קורבנו של איש.

ארבע שנים נמשכה מלחמת האזרחים ברוסיה, שגבתה את חייהם של 15 מיליון בני-אדם ובהם כ-100 אלף יהודים אוקראינים שנטבחו על-ידי הכוחות הלבנים האנטישמיים. ואולם, הצלחת המהפכה והפלת השלטון הצארי המדכא שחררו בבת אחת כוחות עצומים בקהילה היהודית הגדולה שברוסיה.

איש לא האמין שהשינוי יהיה מהיר כל-כך, מאחר שרק חמש שנים לפני כן התרחש "משפט בייליס" – עלילת דם מפורסמת במסגרתה האשימו השלטונות יהודי בשם בייליס באפיית מצות מדם של נוצרים, עלילה שהנסיקה את תופעת האנטישמיות לגבהים חדשים.

עיקר השינוי בא לידי ביטוי במישור הלאומי: ברחבי רוסיה התארגנו קהילות יהודיות מייצגות ודמוקרטיות, וניסיונות להקים נציגות יהודית כל-רוסית קרמו עור וגידים. דו"חות הטלגרף הציפו את מערכות העיתונים בדיווחים על הצהרת בלפור, שהבטיחה להעניק בית לאומי לעם היהודי ושהייתה פרי מאמציו של יהודי יליד "תחום המושב", חיים וייצמן. כל אלו הגבירו את ביטחונם של החוגים היהודיים הלאומיים כי שעת ניצחונם קרבה ובאה.

ואולם, בד בבד עם התחזקותה של המהפכה הבולשביקית, הלכו ודעכו המוטיבציות הלאומיות לטובת אלו האוניברסליות. שיכורים מפירות השוויון נהו היהודים אחר מאמרו של הנביא ישעיהו, "כי ביתי בית תפילה ייקרא לכל העמים", וקבעו כי מדובר בשעת רצון משיחית, זמן לפשוט את המחלצות הלאומיות ולהתאחד עם פועלי כל העולם, ללא הבדל דת, גזע, לאום או מין.

קשה להפריז בחותם שהטביעו יהודים על דמותה של רוסיה בימים שאחרי המהפכה, בין אם כראשי השלטון והמפלגה הקומוניסטית, בין אם כהוגים ובין אם כמפקדי צבא. בכל אלה ועוד מילאו היהודים תפקיד ראשון במעלה, בלא כל מידה לחלקם היחסי באוכלוסייה הכללית.

אך האם עת הזמיר אכן הגיעה? יבואו תולדות יהודי ברית-המועצות ויאמרו את דברן.

ליטא

(מקום)גם לפני האיחוד בין ליטא ופולין מצבם של יהודי ליטא, שהתיישבו באזור במחצית הראשונה של המאה ה-14, היה, פחות או יותר, זהה לאחיהם מפולין, ונע כמטוטלת בין קבלת כתבי זכויות מיוחדות מהנסיכים המקומיים ועד גירושים והתפרצויות אנטישמיות מקומיות-

תוצאה של הסתה דתית נוצרית וקנאה לאור הצלחתם הכלכלית (אף-על-פי שרוב היהודים היו עניים וחיו מהיד אל פה). שיתוף הפעולה הפורה בין הקהילות היהודיות, היותם יודעי קרוא וכתוב וכישרונם הפיננסי הטבעי, העניקו ליהודים יתרון יחסי על פני המקומיים והובילו אצילים רבים להזמינם לנהל את אחוזותיהם. וכך, לצד העיסוקים המסורתיים במלאכות "יהודיות" כמו חייטות, קצבות, סופרי סת"ם ועוד, התגבש מקצוע "יהודי" חדש: חכירת קרקעות וניהול אחוזות של אצילים.

עם הקמת הממלכה המאוחדת של ליטא-פולין (1569-1795) והתעצמות מעמד האצילים בליטא, התחזק כוחם של היהודים החוכרים

שהרחיבו את עסקי החכירה גם לבתי מרזח ופונדקים, בעיקר בכפרים. באותם שנים הגוף שנשא ונתן עם השלטונות היה "ועד ארבע

הארצות" (פולין גדולה, פולין קטנה, ליטא ורוסיה ווהולין) שריכז תחת סמכותו מאות קהילות יהודיות ותיווך בינם לבין השלטונות.

היהודים חיו עם עצמם בתוך עצמם. הם דיברו את שפתם הייחודית- היידיש, ייסדו מוסדות חינוך ובתי דין פנימיים וניהלו את ענייני

הקהילה בכל מעגלי החיים, עד הפרט האחרון. עדות לסולידריות היהודית אפשר למצוא בתגובה של יהדות ליטא לפרעות חמלינצקי

(1648) שהכו באחיהם הפולנים. מיד אחרי הפרעות אסף "ועד מדינת ליטא" מן הקהילות שבתחומו סכומי כסף גדולים לפדיון יהודים

שנפלו בשבי הטטריים, והכריז על אבל ברחבי המדינה. כאות הזדהות נאסר על יהודי ליטא ללבוש בגדים מהודרים ולענוד תכשיטים למשך

שלוש שנים!

סיפוח שטחי ליטא לרוסיה (1772-1795) סימן את ראשית הניסיונות לשילובם של היהודים באימפריה. הרוסים לא סבלו את מצב

העניינים בו היהודים מתבדלים בינם לבין עצמם וכפו עליהם את חובת החינוך הכללי, ("תקנות היהודים", 1804) וכן את הגיוס לצבא

הצאר (גזירת הקנטוניסטים, 1825). גם במישור הכלכלי נפגעו היהודים עם פיחות מעמד האצילים ואיתם עסקי החכירות שהלכו ונתמעטו.

רעיונות ההשכלה שחדרו למרחב היהודי, שעד אז הסתיים בסוף העיירה, גרמו ל-"רעידת אדמה" תרבותית. נערים קראו בסתר ספרות

זרה, בנות החלו ללמוד ב-"חדרים" המסורתיים, ואת הזקן המסורתי החליפו פנים מגולחות למשעי ומשקפי צבט אופנתיות. שינויים אלו

הובילו למשבר במוסד המשפחה. בנים עזבו את הבית כדי לרכוש השכלה ושיעור מספר הגירושין גדל. הסיפור הנפוץ באותה תקופה היה,

שליהודי ליטא ופולין יש סימן: אם בבית מוצאים שתי בנות בוגרות, לא שואלים אם הראשונה התגרשה, אלא מתי התגרשה השנייה. זאת

ועוד: במחצית השנייה של המאה ה-19 התרחש מעבר המוני של יהודים לערים הגדולות וילנה, קובנה ושאולאי. החברה היהודית

הליטאית הפכה להיות "חברה נוסעת" ופרנסות ישנות כמו נגרות וסנדלרות נדחקו לטובת מקצועות חופשיים כמו בנקאות ופקידות.

ליהדות ליטא ישנו גם קשר מיוחד לארץ ישראל, כשבשנת 1809 עלו לארץ מספר גדול של תלמידי הגאון מווילנה- הגר"א (על הגר"א ראה

במשך ציר הזמן) והתיישבו בצפת וירושלים. עולים אלו ייסדו את בית חולים "ביקור חולים" בירושלים וכן סייעו בהקמת המושבות גיא

אוני, פתח תקווה ומוצא.

1850 | ירושלים דליטא

באמצע המאה ה-19 החלה להתגבש קהילה יהודית גדולה בעיר וילנה. בשנת 1850, למשל, חיו בווילנה כ-40 אלף יהודים. וילנה,

שכונתה "ירושלים דליטא", נחשבה למרכז יהודי רוחני ראשון במעלה. בעיר זו התגבשה דמותו של "הלמדן הליטאי", שהאב-טיפוס שלו

היה רבי אליהו בן שלמה זלמן (הגר"א, 1720–1797).

הגר"א, הידוע בכינויו "הגאון מווילנה", נחשב כבר בילדותו לעילוי. נאמר עליו כי "כל דברי התורה היו שמורים בזכרונו כמונחים בקופסה"

והאגדות מספרות שכבר בגיל עשר החל לשאת דרשות בבית-הכנסת. הגר"א התפרסם במלחמת החורמה שניהל נגד תנועת החסידות.

הוא עצמו התגורר בבית צר מידות והסתפק במועט. הוא מעולם לא נשא במשרה ציבורית והתפרנס מקצבה זעומה שקיבל מהקהילה

היהודית. הגר"א היה בקיא גם במתמטיקה, אסטרונומיה, דקדוק עברי ועוד.

לדעת חוקרים רבים, אחת הסיבות לפריחתה של תנועת ההשכלה בקרב יהודי ליטא היתה העובדה שמשכילים רבים היו בעברם תלמידי

ישיבות עם יכולות אינטלקטואליות יוצאות דופן, פועל יוצא של אתוס "הלמדן" שעוצב בצלמו ובדמותו של הגאון מווילנה.

גם לדפוס היה חלק ניכר בהפצת ההשכלה בעולם הליטאי. בשנת 1796 הוקם בווילנה דפוס עברי, ובשנת 1799 העביר רבי ברוך ראם את

בית-הדפוס שלו מעיירה ליד גרודונו לעיר וילנה. בבית-הדפוס הזה הדפיסו לימים את התלמוד הבבלי. בשנת 1892 נפתחה בווילנה

ספריית סטראשון, שהפכה לימים לאחת הספריות היהודיות הגדולות באירופה.

במחצית השנייה של המאה ה-19 דרך כוכבה של הספרות העברית בווילנה. "ירושלים דליטא" היתה כור מחצבתם של כמה מאבות

השירה והפרוזה העברית, ובהם אברהם דב לוינזון (אד"ל), מיכה יוסף (מיכ"ל), ר' מרדכי אהרן גינזבורג ויהודה ליב גורדון (יל"ג), אשר

שילבו ביצירתם בין ישן לחדש ופתחו לקוראיהם היהודים חלונות של דעת והשכלה.

1880 | הווה גולה למקום של תורה

דמותו של התלמיד החכם הליטאי היתה אספקלריה של הפרופיל היהודי הליטאי הכללי, שהיה "לפי טבעו איש השכל, ההיגיון, צנוע ועניו,

העובד את ה' מתוך הבנה שזוהי הדרך. הוא אינו מאמין שהרבי יודע לעשות נפלאות מחוץ לגדר הטבע". (הציטוט לקוח מתוך הספר

"בנתיבות ליטא היהודית" תשס"ז, עמ' 11)

מייסד עולם הישיבות הליטאי היה הרב חיים מוולוז'ין, תלמידו של הגאון מווילנה. ר' חיים קיבץ את כל הישיבות הקטנות שהיו פזורות

לאורכה ולרוחבה של ליטא וריכז אותן תחת ישיבה אחת בעיר וולוז'ין. ישיבת וולוז'ין פעלה עד שנת 1892 והיתה לסיפור הצלחה. ר' חיים

מיתג אותה מראש כאליטיסטית, עובדה שהובילה אלפי בחורים מכל מזרח אירופה לנסות להתקבל אליה ובכך לקיים את הציווי הדתי

"הווה גולה למקום של תורה".

ר' חיים אימץ את תפיסתו החינוכית של הגר"א, שהסתייג מפלפול לשמו והנהיג לימוד שיטתי של התלמוד. זאת, בניגוד לנוהג שרווח

בישיבות הגדולות בפולין, שנקטו את שיטת השקלא והטריא (השיג והשיח הפלפולי).

בשנת 1850 החל להתגבש בליטא זרם דתי חדש, זרם המוסר, שלטענת חוקרים רבים היה תגובת נגד לרוח השכלתנית והרציונלית

שנשבה מישיבת וולוז'ין. מייסדו של הזרם היה הרב ישראל מסלנט, עיירה בצפון-מערב ליטא. לשיטתו של זרם המוסר, שהזכיר תפיסות

נוצריות קתוליות, האדם הוא חוטא מנעוריו ועליו לבחון את עצמו ולנסות לתקן את מידותיו בעזרת הלימוד. מרחב התיקון היה הישיבה,

שהקצתה כמה שעות ביום ללימוד ספרי מוסר, ובראשם "מסילת ישרים" לרמח"ל (רבי משה חיים לוצאטו).

בשנת 1881 נוסדה בפרברי העיר קובנה ישיבת סלובודקה, שהיתה הראשונה והמובהקת מבין ישיבות זרם המוסר. לימים הוקמו בליטא

גם ישיבות מוסר נוספות, בין השאר בעיירות נובהרדוק וקלם.

1903 | בונד-ינג

בעקבות הפוגרומים ביהודי דרום-מערב האימפריה הרוסית בשנים 1881-2 ("הסופות בנגב") נמלטו רבבות מיהודי ליטא למערב, בעיקר

לארצות-הברית, לדרום-אפריקה ולארץ-ישראל. בימים ההם נמצאו לתנועה הציונית תומכים רבים בקרב יהודי ליטא. בנימין זאב הרצל

חזה כי התנועה הציונית תתנחל בלבבות יהודי מזרח אירופה יותר מאשר בקרב יהודי מערב אירופה, שרבים מהם איבדו כל זיקה לזהותם

היהודית. ואכן, כשביקר הרצל בליטא, בשנת 1903, קיבלו אותו ההמונים בכבוד מלכים. גם לתנועות הנוער של השומר-הצעיר, החלוץ,

בית"ר וצעירי-המזרחי, שעשו בליטא נפשות למפעל הציוני, היה חלק בזיקה ההולכת וגוברת של יהודי ליטא לציונות.

בד בבד פרחה שם גם השפה העברית, בזכות פעילותם של רשת בתי-הספר העבריים תרבות, הגימנסיה הריאלית העברית, תיאטראות

ובהם הבימה-העברית וכן עיתונים עבריים, שהנפוץ שבהם היה העיתון הווילנאי "הכרמל".

ואולם, ליטא לא היתה רק בית-גידולם של ציונים נלהבים, אלא גם ביתה של הנמסיס של התנועה הציונית, תנועת הבונד, שדגלה

באוניברסליות סוציאליסטית וקנאות לשפת היידיש. תנועת הבונד, שנוסדה בווילנה ב-1897 (הלוא היא שנת הקונגרס הציוני הראשון

בבאזל), כמעט נשכחה מהזיכרון הקולקטיבי היהודי. ואולם, בימים ההם של ראשית המאה ה-20, כשהרעיון הסוציאליסטי היכה שורש

ברחבי אירופה בכלל ובעולם היהודי בפרט, היתה התנועה פופולרית ביותר. עדות לעוצמתה היתה ההפגנה הגדולה שאירגנה בווילנה

באחד במאי 1900, ובה השתתפו כ-50 אלף איש.

1914 | אני הייתי ראשונה

עם פרוץ מלחמת העולם הראשונה נפוצה בליטא עלילה ולפיה קומץ יהודים מקוז'ה, כפר סמוך לעיר שאולאי, סייעו לאויב הגרמני ואותתו לו בלילות על תנועת כוחות צבאו של הצאר. העלילה העניקה לשלטונות הרוסיים הצדקה לגירוש של רבבות יהודים מבתיהם. המגורשים התפזרו ברחבי רוסיה הדרומית. לרבים מהם, במיוחד לבני הנוער, היתה זו הפעם הראשונה מחוץ לתחום המושב הליטאי. רבים מהמגורשים, ובהם בני ישיבות, התערו בחיים הסואנים והססגוניים של ערי רוסיה הדרומית ורחקו ממורשת בית אבא.

היהודים שנותרו בליטא נאלצו לחיות תחת שלטונה של גרמניה הקיסרית, שהנהיגה משטר צבאי חמור וחייבה אותם בעבודות כפייה גם

בשבתות ובחגים היהודיים. מנגד, השלטונות התירו ליהודים להתקבל לעבודה בשירותים הציבוריים, בעיריות, בדואר וברכבות – תחומים

שהיו סגורים בפניהם בעבר. הגרמנים אף הגדילו לעשות והתירו ליהודים להקים בתי-ספר, ספריות, מועדונים ותיאטרון ביידיש. בכך הזרימו שלטונות גרמניה חמצן יקר ערך לתרבות היהודית הליטאית, שספגה מכה קשה עם פרוץ המלחמה.

בסוף המלחמה, עם התמוטטות החזית הרוסית וכריתת ברית השלום בין רוסיה הסובייטית לגרמניה, קמה לתחייה מדינת ליטא

העצמאית. כ-100 אלף יהודים שבו אז בקבוצות מאורגנות ("אשלונים") מרוסיה לליטא והצטרפו לכ-60 אלף היהודים שהקדימו לחזור

לליטא לבדם או בקבוצות קטנות.

1921 | תור הזהב של יהדות ליטא

התקופה שבין שתי מלחמות העולם נחשבת לתור הזהב של יהדות ליטא. עם כינונה של ממשלת ליטא העצמאית זכו היהודים לאוטונומיה

ולשוויון זכויות מלא, וכן לייצוג במועצה המחוקקת הליטאית הראשונה (ה"טאריבא"). חרף העובדה שבשלהי 1921 חלק גדול ומשמעותי

מהקהילות היהודיות הליטאיות – ובראשן קהילת וילנה – נותר מחוץ לגבולות מדינת ליטא העצמאית, הקיבוץ היהודי בליטא מנה למעלה

מ-80 קהילות מאורגנות, שנבחרו בבחירות חופשיות. עולם הישיבות המפוארות – פוניבז', סלובדקה, טלז – חזר לימי גדולתו. העיתונות

והספרות פרחו, והיידיש והעברית משלו בכיפה.

כמו בכל העולם היהודי, גם בליטא התקיימה פעילות לאומית תוססת. ארגוני נוער והכשרות מכל הגוונים גידלו דור של נוער יהודי-חלוצי.

לצדם פעלו המפלגות הלאומיות, ובהן הבונד הסוציאליסטית; תנועת המזרחי, שנציגיה מילאו תפקיד פעיל בצמרת העסקנות הציונית;

הרביזיוניסטים; והשומר-הצעיר. בליטא פעלו מאות גני ילדים לצד רשת בתי-הספר העבריים של תרבות ומפעל הגימנסיות העבריות,

שהפעיל 13 בתי-ספר לאורכה ולרוחבה של ליטא.

ברם, התגברות האנטישמיות בכל רחבי אירופה, כמו גם התחזקותן של תנועות פשיסטיות, זלגו גם לליטא.

בשנת 1926 פרצה המהפכה הפשיסטית של הלאומנים הליטאים. המפלגות הדמוקרטיות פוזרו ורובן ירדו למחתרת. כעבור כשנתיים,

בשנת 1928, חוסלו רשמית שרידיה של האוטונומיה היהודית, וממשלת ליטא העבירה לרשות הקואופרטיבים המקומיים ענפים רבים מן

המסחר והתעשייה, ובכללם ייצוא התבואה והפשתן, שהיו עד אז מקור מחיה עיקרי של היהודים.

1941 | בשם האבא

באוגוסט 1939, עם חתימת הסכם ריבנטרופ-מולוטוב בין נציגי גרמניה הנאצית לרוסיה הקומוניסטית, איבדה מדינת ליטא את עצמאותה.

עוגת מזרח אירופה נפרסה לפרוסות דקות, וליטא, על מגוון תושביה, נבלעה על-ידי הענק הסובייטי. אף שהיהודים היו הגרעין הקשה של המפלגה הקומוניסטית, הם לא זכו לעמדות משמעותיות בממשל החדש בליטא. לא זו אף זו: הליטאים זיהו את היהודים עם הכיבוש הסובייטי, ואיבתם כלפיהם הלכה וגברה. בד בבד הוצאה התנועה הציונית אל מחוץ לחוק, וכל בתי-הספר שלימדו בעברית נכפו ללמד ביידיש.

בשנת 1941, עם הפרת הסכם ריבנטרופ-מולוטוב על-ידי גרמניה וכיבושה של ליטא על-ידי הנאצים, הופקדו יחידות המוות של

האיינזצגרופן על חיסול היהודים. החל ב-3 ביולי 1941 הוציאו היחידות הללו לפועל תוכנית השמדה שיטתית, אשר בוצעה לפי לוח זמנים

מדויק. רבים משלבי ההשמדה – איתור הקורבנות, שמירה עליהם, הובלתם לגיא ההריגה ולעתים גם הרצח עצמו – בוצעו בידי כוחות עזר

ליטאיים, ובהם אנשי צבא ומשטרה. מעשי הטבח ההמוניים בוצעו לרוב ביערות שבקרבת היישובים, על שפת בורות גדולים שלחפירתם

גויסו איכרים, שבויי מלחמה סובייטים ולעתים אף היהודים עצמם. בהמשך הועברו היהודים שנותרו בעיירות הקטנות לגטאות שהוקמו

ביישובים הגדולים הסמוכים.

פרק מפואר בתולדות יהדות ליטא בזמן השואה מיוחד לתנועת ההתנגדות של הפרטיזנים. את נס המרד הניף הפרטיזן אבא קובנר, שטבע את האמירה "אל נא נלך לטבח", והקים יחד עם חבריו, יוסף גלזמן ויצחק ויטנברג, את הארגון הפרטיזני המאוחד (FPO), שפעל ביערות. הארגון הצליח להשיג תחמושת, הוציא עיתון מחתרתי וביצע מעשה חבלה רבים, אך תרומתו המרכזית היתה החדרת רוח של גאווה

וכבוד בקרב יהודי ליטא. עד תום מלחמת העולם השנייה הושמדו 94% מיהודי ליטא – כ-206,800 איש.

2000 | ליטא כבר לא מכורתי

עם תום מלחמת העולם השנייה חזרה ליטא להיות רפובליקה סובייטית. רוב בני הקהילה היהודית לא הורשו לעלות לישראל, ובהתאם

לאידיאולוגיה הקומוניסטית, נאסרה עליהם כל פעילות לאומית ודתית. למרות זאת, בעקבות לחץ בינלאומי, התירו השלטונות הרוסיים את

הקמתו של תיאטרון יידי.

מפקד אוכלוסין משנת 1959 מלמד כי יהדות ליטא מנתה אז כ-24,672 יהודים, אשר רובם התגוררו בווילנה ומקצתם בקובנה. בתחילת

שנות ה-70 של המאה ה-20 החלה עלייה מסיבית של יהודים מליטא לישראל, וזו אף גברה לאחר נפילת ברית-המועצות בשנת 1989.

בשנת 2000 מנתה הקהילה היהודית בליטא כ-3,600 יהודים בלבד, כ-0.1% מכלל האוכלוסייה. בשנת 1995 ביקר בישראל נשיא ליטא, אלגירדס ברזאוסקס, וביקש סליחה מהעם היהודי מעל בימת הכנסת. רמת האנטישמיות בליטא בשני העשורים האחרונים נחשבת מהנמוכות ביותר באירופה.

לטביה

(מקום)Latvia

Latvijas Republika - Republic of Latvia

A country in the Baltic region of northern Europe, member of the European Union (EU). Until 1991 part of the Soviet Union.

21st Century

Estimated Jewish population in 2018: 4,700 out of 2,000,000 (0.2%). Main Jewish organization:

Council of Jewish Communities of Latvia

Phone: 371 672 85 601

Email: jewishlv@gmail.com

secretary@lvjewish.lv

מולדובה

(מקום)Moldova

Republica Moldova - Republic of Moldova

A country in eastern Europe, it covers most territory of the historic region of Bessarabia, part of Soviet Union until 1991, it was part of Romania between the two World Wars and of the Russian Empire until 1918.

21st Century

Estimated Jewish population in 2018: 2,000 out of 3,500,000. There were 12 municipal organizations and 9 regional communities in the cities of Balti, Soroca, Orhei, Cahul, Ribnita, Dubasari, Bender, Tiraspol, Grigoriopol. Main umbrella Jewish organization:

Jewish Community of the Republic of Moldova

Phone: 373(22)509689

Email: office@jcm.md

Website: https://www.jcm.md/en

אסטוניה

(מקום)Estonia

Eesti Vabariik - Republic of Estonia

A country in northern Europe, member of the European Union (EU). Until 1991 Estonia was part of the Soviet Union.

21st Century

Estimated Jewish population in 2018: 1,900 out of 1,300,000 (0.19%). Main Jewish organization:

The Jewish Community of Estonia

Phone: 372 6623034

Email: community@jewish.ee

Website: www.jewish.ee

אוקראינה

(מקום)Ukraine

Україна / Ukrayina

A country in eastern Europe, until 1991 part of the Soviet Union.

21st Century

Estimated Jewish population in 2018: 50,000 out of 42,000,000 (0.1%). Main Jewish organizations:

Єврейська Конфедерація України - Jewish Confederation of Ukraine

Phone: 044 584 49 53

Email: jcu.org.ua@gmail.com

Website: http://jcu.org.ua/en

Ваад (Ассоциация еврейских организаций и общин) Украины (VAAD – Asssociation of Jewish Organizations & Communities of Ukraine)

Voloska St, 8/5

Kyiv, Kyivs’ka

Ukraine 04070

Phone/Fax: 38 (044) 248-36-70, 38 (044) 425-97-57/-58/-59/-60

Email: vaadua.office@gmail.com

Website: http://www.vaadua.org/

גיאורגיה

(מקום)Georgia

საქართველო / Sakartvelo

A country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia, until 1991 part of the Soviet Union.

21st Century

Estimated Jewish population in 2018: 1,600 out of 3,700,000. There are synagogues in Tbilisi, Kutaisi, Batumi, Gori, Oni. Main Jewish organizations:

The Jewish Community of Georgia (JCC) - Jewish Cultural and Educational Community Center

0103, Tbilisi, st. Vakhtang VI No. 30

Phone: 995 32 2770653

E-mail: jcc.tbilisige@gmail.com

Union of Jews of Georgia

Tbilisi 0105, Grigola Abashidze Street No. 14

Phone: 995 577 522 111; 995 577 408 022

E-mail: eduard72002@yahoo.com

HISTORY

The History of the Jews of Georgia until the Communist Regime

By Gershon Ben-Oren

The article was originally published in In the Land of the Golden Fleece - The Jews of Georgia-History and Culture. Beth Hatfutsot - Ministry of DEfence Oublishing House, Tel Aviv, 1992

Very little is known about the history of the Jews of Georgia. Up until the end of the 18th century there exist only the barest hints of information on Georgian Jews, based on bits of testimony preserved orally or in writing, or contained in travelogues. Minimal archeological evidence exists, as well, from the 18th century on the picture becomes clearer, thanks to jfficial documents preserved primarily in the archives of churches md monasteries. These are supplemented, by 19th century locuments of the Russian government.1 During this period Russian

began to show interest in the Jews of the Caucasus; information about these Jews is found scattered in the Russian wish press, as well as in the writings of the Jewish traveler Joseph herny, who traveled throughout Georgia in the 1860s and 1870s.2 e first attempts to investigate the history of the Jews of Georgia were made at the end of the 19th century, primarily by researchers interested in the myth of the Ten Lost Tribes and the mystery of the Khazar kingdom.3 Methodological scientific research began in the 1930s, mainly by scholars at the Historical and Ethnographic Museum of the Jews of Georgia that operated in Tbilisi.4

This activity was brought to an end when the museum was closed in 1951, and some of the studies have never been published. Since then, only a few individuals have dealt with this subject, the most prominent being Nissan Babalikashvili. Following the recent developments in the Soviet Union, both Jewish and non-Jewish researchers have begun to show renewed interest in the history of the Jews of Georgia, and it is hoped that their research will uncover hitherto unknown source material.

In light of the above, it is not surprising that little has been written about the history of the Georgian Jews,5 and this article can only summarize the little that is known.

Traditions Regarding the Arrival of the Jews in Georgia

An oral tradition, passed from generation to generation by Georgian Jews, ascribes their origin to the Ten Tribes exiled by Shalmaneser, King of Assyria, who settled them "in Halah and Habor, at the River of Gozan and in the cities of the Medes" (Kings II, 17:6). The Jews of Daghestan and Kurdistan share this tradition. Researchers seeking support for this theory cite the dispute of the Talmudic sages concerning the location of the Ten Tribes: "Where did they go? Mar Zutra said: To Afrike" (Sanhedrin 94). According to these researchers, Afrike - which appears in various places in the Talmud - is Iberia, the ancient name for eastern Georgia. They reached this conclusion because the name Iberia was pronounced Iberika in Greek and Latin, and was transformed in Hebrew into Afrike-Efrika. There are those who bring further support for the antiquity of Jewish settlement in the Caucasus by identifying the name Cassiphia with the lands bordering the Caspian Sea. According to this claim, Ezra sent messengers there in search of Levites for the Temple: "And I sent them with a charge unto Iddo the chief at the place Cassiphia, and I laid the words in their mouth to speak unto Iddo and to his brother, who were appointed at the place Cassiphia, that they should bring unto us ministers for the house of our G-d" (Ezra 8:17).5

Regardless of these and other attempted proofs, the idea that the Jews of Georgia originated among the Ten Tribes is strictly legendary, without any scientific basis.

The most ancient written tradition known today appears in the chronicles of Georgia, Kartlis Tskhovreba. This source relates the Jews' arrival in Georgia to the destruction of the First Temple (586 BCE): "Then Nebuchadnezzar the King captured Jerusalem, and the Jews who escaped came to Kartli and requested land from the Mamasakhlisi (prince, chief of a tribe or clan) of Mtskheta in return for the payment of a head tax. He gave them land near Aragvi, near a spring called Zanavi, and settled them there. The place they received in exchange for payment of the head tax is called today Kherek, because of the tax."

Another reference in Kartlis Tskhovreba tells of Jewish refugees who reached Georgia after being exiled by Vespasian and settled in Mtskheta, near their brethren who had settled there long before.7 These Jews were called Una or Huria, a term common in early Georgian sources and those of the late Middle Ages. In the 19th century, this term was replaced by Ebreili, while the term Uria became a pejorative for Jews.8

The Kartlis Tskhovreba was edited only in the llth century, so one must relate to the traditions it cites with caution, even if they are based upon very early sources; it is quite possible that these traditions originated in an attempt to link the arrival of Jews in Georgia to known historical events.

Nonetheless, there is room for assumption that Jewish settlement preceded the Christian era. Georgia was located within the realm of influence of the great eastern empires of the ancient world -Assyria, Babylonia and Persia - and maintained commercial and cultural ties with them. Jews were likely to come to Georgia as traders, emigrants or refugees, from the various lands of their dispersal, especially during the period when Georgia was part of the Persian empire. It should be noted that in Armenia (Georgia's southern neighbor) as well, there existed a large Jewish settlement during the lst-4th centuries.

From a passage in the Kartlis Tskhovreba one learns that the tradition of counting the Jews among the residents of Georgia was already accepted at a very early period. The entry states that Hebrew was among the languages spoken in Georgia. "And in Kartli they spoke six languages - Armenian, Georgian, Khazaric, Aramaic, Hebrew and Greek, and all the kings of Kartli, fathers and mothers, knew these languages."

The earliest archaeological evidence of a Jewish presence in Georgia consists of tombstones found near Mtskheta. The monuments, thought to be from the 3rd-5th centuries, bear engraved inscriptions in Aramaic and Hebrew. The influence of the Georgian language can also be discerned in the spelling. The Georgian name Cork, originating in the Persian language, appears on one of the stones -that of "Yehuda who was named Cork." On another, that of Yosef bar Hazan, a goblet and pitcher are engraved.11 Jews occupy a special place in Georgian traditions about the spread of Christianity in the country. A legend cited in several versions of Kartlis Tskhovreba links the Jews of Georgia with the story of Jesus' crucifixion. It tells of emissaries from Jerusalem who presented themselves before the Jews of Georgia and asked them to choose sages from among themselves, who would travel to Jerusalem and take part in Jesus' trial. Two distinguished Georgian Jews went to Jerusalem - Elioz of Mtskheta and Longinoz of Karasani. They were present at the crucifixion, and took home with them Jesus' robe. Upon their return to Georgia, Elioz' sister went out to greet them and embraced the robe to her heart. She then became so grief-stricken over the death of Jesus that she fell down and died. She was buried with the robe in her arms, and at the site of her grave in Mtskheta there grew a cedar brought from Lebanon.12 A folk legend relates that a certain tombstone in the center of the Svetitskhoveli cathedral in Mtskheta marks her grave. It may be that this legend contains a hint that there were "Christian Jews" among the Jews of Georgia even before St. Nino began preaching Christianity.

At the center of the traditions about the spread of Christianity in Georgia stands the figure of Nino, a woman who came from Cappadocia around 330 CE. It is told that she began her mission in the village of Urbnisi, located about 100 kilometers from Mtskheta, and inhabited by many Jews. There are those who hold that the name Urbnisi originated in the term Uriat Ubani, meaning "Jewish neighborhood." The legend relates that Nino was received kindly by the Jews, since she spoke their language - Hebrew. Among her first pupils were Abyatar the Priest, who was -according to the story - the grandson of Elioz, and his daughter, Sidoniya. According to these traditions, Abyatar - who is called Uriakopili, that is, "the former Jew" - "knew the Old Covenant very well, and sought the covenant of Christ without fear and with dedication." He also taught his new faith to many people, including King Marian and Queen Nana. Sidoniya, who followed Nino along with six Jewish mothers, was witness to the miraculous deeds performed by the missionary. Some of the stories about Nino are told in the name of Abyatar and Sidoniya.1

The Christianizers brought about a schism in the Jewish community. Tradition tells of men who sought to stone Abyatar, and only the intervention of the king saved him. When Nino baptized the king and most of the residents of Kartli with him, there were no Jews of Mtskheta among them, but only fifty families, descendants of Barabbas (the thief who was saved from crucifixion alongside Jesus and who, as legend has it, reached Mtskheta).

There is no question that the legendary element in these sources is quite extensive, and it is difficult to determine the grains of truth. It is known that Christian missionaries in different countries viewed the Jews as a primary target for their teachings, and there arose in the Jewish diaspora communities of "Christian-Jews" who viewed Christianity as a form of renewal of the Jewish faith. It is reasonable to assume that in Georgia, too, Christian ideas were accepted by the Jews before they were accepted by the native Georgians, whose beliefs were influenced by the Persian religion. It is probable, however, that these traditions were fostered by the Church with the aim of strengthening the position of Christianity in Georgia at the beginning of its development, and to grant it legitimization. In any case, one may conclude that a large and well-established Jewish community existed in Georgia at the beginning of the 4th century, even if it is not possible to estimate its size or relative proportion to the general population. Testimony to the fact that a stable Jewish community existed in Georgia two hundred years later may be found in a 6th-century Georgian source. This document relates the story of a Persian youth who fled his homeland and traveled to Mtskheta, to learn about the Christian and Jewish faiths in order to choose between them. It is told that he entered a synagogue, whose status is described as equal to that of the prayer houses of the other religions in Mtskheta.14

The Jews in the Middle Ages

While knowledge about the history of the Jews of Georgia up until the 4th century is scarce and unclear, even less information is available regarding their fate during the Middle Ages. The known Georgian sources from the 4th-17th centuries hardly mention the Jews. Furthermore, there are very few archaeological finds or Jewish manuscripts from this period. Nonetheless, it remains difficult to disprove the tradition of ancient and continuous Jewish settlement on Georgian territory.

During the 7th century, the Moslem Empire grew even stronger, and following the conquest of Persia and Armenia, Georgia was conquered as well (642-643). Arab emirs ruled large portions of the land until 1122. In 10th-12th century Jewish sources outside Georgia, Georgian Jews are mentioned in connection with the struggle between the Karaites and the rabbinical Jews. Karaite scholars who describe the development of the Karaite movement and its internal sects mention a group called Tifilssi. This name stems from the epithet applied to the group's founder, Musa (Moshe, Moses) az-Za'farani, who seems to have come from Baghdad to Tiflis (Tbilisi) during the second half of the 9th century. Yehuda Hadassi described him as "Musa az-Za'farani, known as abu-Imran al-Tiflisi, who moved from his homeland to the state of Tiflis."15 We have so little information about az-Za'farani's group, that it is difficult to determine whether its center existed in Tbilisi for very long. However, one may assume that the group's followers spread elsewhere in the east. Be that as it may, from the very fact of the group's existence, one may draw the conclusion that there were contacts between Georgian Jews and the neighboring Jewish communities.

Other sources mention the Jews of Georgia as being rabbinical Jews. The RAVAD (Rabbi Avraham ben David), in his book Seder Hakabala ("Order of the Tradition"), lists the Jews "of the land of Girgashi, that is called Girgashtan [i.e., Georgia]," among the communities faithful to rabbinical Judaism.16 Benjamin of Tudela, who visited Babylonia (Iraq) during the second half of the 12th century, relates that in Baghdad, the headquarters of the Reish Galuta ("Head of the Diaspora"), he observed Jews from various eastern countries, including some who lived in "the land of Gargain on the river of Gihon, and they [the people there] are the Girgashis and they are of the Christian religion. These Jews were granted permission by the 'Head of the Diaspora'... to appoint a rabbi and hazan (cantor) over every congregation since they come to him to receive ordination and authorization and bring him gifts and presents." Ptakhia of Regensburg, another Jewish traveler of the period, writes of the Jews from "the land of Ararat" (a name applied to the southern Caucasus), mentioning Jews he met in Baghdad who called themselves "Jews from the land of Meshech" and teach their children Torah and the Jerusalem Talmud. It is customary to identify Meshech - mentioned in the Bible as one of the northern peoples - with the south Georgian tribe of Meskhi. From these sources, it may be concluded that in the 12th century the Jews of Georgia were within the circle of influence of the yeshivot (talmudic academies) of Babylonia.1 We learn a bit about the spiritual life of Georgian Jewry in the Middle Ages from a manuscript written in the town of Gagra on the shore of the Black Sea in 1208, dealing with Hebrew language and grammar 18.

Unfortunately, we have no additional information about the Jews during the period of Georgian independence and prosperity, which began during the days of King David "the Builder" (1089-1125) and reached its apex during the "Golden Age" of Queen Tamar (1184-1213). However, one may assume that the unification of Georgia under the House of Bagration and the development of trade and crafts, brought about an improvement in the Jews' status. Marco Polo, who passed through Georgia in 1272, notes that "Tiflis is inhabited by Georgian and Armenian Christians, as well as a number of Moslems and Jews." The book of Georgian chronicles refers to a certain "captain of trade" - (did-vattsari) named Zanchen Zerubavel, who was sent by the royal court to bring Queen Tamar's bridegroom from Russia. There are those who believe this Zerubavel was a Jew.19

The Mongol conquest put an end to Georgian independence and brought death and destruction upon the land; undoubtedly, this dealt a blow to the Jews as well. Nevertheless, a hint of the existence of Torah learning and centers of Jewish spiritual creativity among the Georgian Jews during the 14th century may be discerned in the writings of Rabbi Isaiah of Tabriz. In the introduction to his kabbalistic Sefer Hakavod ("Book of Honor"), the author introduces himself as "Isaiah, who is called Rabbi, son of our Rabbi Yosef al-Tiflisi, may his memory be for a blessing."20

The main source about the condition of the Jews during the Middle Ages is a collection of documents from the 17th-19th centuries published by the Historical and Ethnographic Museum of the Jews of Georgia. These documents shed light on the judicial, social and economic condition of the Jews toward the end of the Middle Ages, and perhaps during previous centuries as well, if one assumes that their situation remained static.21

The status of the Jew was determined by his place in the feudal system practiced in Georgia during the Middle Ages and up until the middle of the 19th century. As a rule, Jews belonged to the serf class - kamani - that is, persons having a master. This class included peasants, craftsmen and petty traders. Jewish serfs, like others, were divided into different types, each with its own distinct economic status, rights, obligations, and degree of dependency on the master. The Jews, whose traditional occupation was trade, remained, for the most part, petty traders and peddlers moving from village to village, although many had small plots of land as well, mainly for growing fruit trees and viticulture. Some Jews were craftsmen; others, who had no property at all, received from their masters a house and plot of land, and the right to trade and to run the master's stall or shop. The Jews who owned property of their own were permitted both to sell and to purchase more land. Jews are mentioned in many documents as involved in the buying and selling of land, houses, vineyards and other agricultural property. It is also known that there were Jews who were themselves masters of serfs, including Christian serfs. There is no doubt that many Jews were quite well-to-do.

The rights and obligations of the serfs - Jews and others - were defined in connection with the factors that led to the person becoming enserfed. Persons who became serfs of their own free will, because they sought a master to defend them, had greater rights than serfs who were sold by their former masters, or transferred to new owners as presents or dowry or in payment of debts. As the status of serfs donated to churches or monasteries was writing by the former masters, they were protected somewhat from tyranny. We learn, for example, from a document dated 1789 that three Jewish serfs engaged in trading activities were donated by Queen Miriam of Imereti to the monastery of Gelati, and their obligations were defined as the yearly payment of a tax of 15 mirtsil (a monetary unit) and a liter of candle wax.22 Serfs differed in the degree of freedom of movement they were granted and in the amount of taxes and labor obligations placed upon them. Taxes were usually paid in various products, rather than money, and labor obligations were met either in the master's domestic economy or in his fields. Serfs had to pay for special rights, such as the use of pasturage or the engaging in trade. They were obligated to give their masters presents on various occasions, such as family events and holidays, and to be at their service when needed. Serfs were also obligated to appear for military service if called upon to do so by their lords. Jews usually bought exemption from this obligation by paying special taxes. Apart from taxes paid to the master, serfs had to pay royal and church taxes as well. The status of a serf was directly related to the type of master to whom he belonged. There were serfs of the king, serfs belonging to a church or monastery, and serfs indentured to princes. In general, the latter were considered to be in the worst position. From the 17th century, as the central government became weaker and the economic condition of the princes declined, the tendency to exploit the serfs increased, and the burden of taxation placed upon them grew heavier.

Princes did not hesitate to separate families or to uproot serfs from their homes and communities if they needed them as payment for debts, or as part of a dowry or gift. In many cases, Jews were victims of pillage and kidnapping by robber-princes.24 Documentary sources indicate numerous cases of cruelty and extortion, leading Jewish serfs to flee the tyranny of their masters in favor of the patronage of monasteries or the monarchy.

The Jews' judicial status was, as stated above, identical in every way to that of the other serfs. Nevertheless, it is still possible that there were some masters who, moved by religious zealotry, treated the Jews harshly, and that the Jews, because they belonged to a minority group, found it more difficult to defend their rights. Even if they were not discriminated against by law, it may be supposed that their identity as Jews limited their opportunities for social advancement. The feudal system in Georgia left quite a wide leeway for social mobility, and movement from group to group within the serf class was common. Anyone who became the subject of his master's kindness, thanks to his loyalty or faithful services, could join the ranks of the Tarkhani group which granted him privileges and exemptions from obligations.

Documents mention only isolated cases of Jews who were granted membership in this group, but many examples of those labelled "former Jews" who were both Tarkhani and "warriors." Testimony that a Jew could improve his condition by converting to Christianity may be found in a document dated 1746: The Jew, Daniel Aranashvili, received an exemption from all taxes after he was baptized as a Christian.25 Folk tales cited by Tcherny26 tell of Jews who became important figures in the King's court, but these stories are not mentioned in any documents. Neither do the sources make clear whether Jews were among the important merchants involved in international trade.

The political disintegration of Georgia during the 15th-19th centuries, and the absence of political stability, severely harmed all strata of the population. The number of people in Georgia declined greatly, and entire regions were abandoned. The Jews also experienced great suffering; echoes of those difficult days were preserved in testimonies that Tcherny heard from Georgian Jews. Invasions by Moslem tribes from the eastern Caucasus or from Adzharia, and military campaigns by the Persian and Turkish armies, forced entire communities to abandon their homes and seek new places of settlement time and time again.27 During the 15th-18th centuries, Georgia, like the rest of the Caucasus, was an inexhaustible source of slave trade. Thousands of Georgian residents, mainly boys and girls, were sold each year in the slave markets in Akhaltsikhe, Tabriz, Trebizond and Constantinople. Some were sold for profit by their masters, while others were kidnapped to fill the quota of slaves demanded by the rulers of Persia and Turkey as part of the tribute demanded from conquered territories. The Jews, too, were forced to pay their share of this cruel tax.

There are various testimonies which lead us to assume that the number of Georgian Jews declined drastically during the Middle Ages, to a much greater extent than the decline in the general population. This assumption rests largely on oral traditions from various regions of Georgia; according to these traditions a large Jewish population once existed in these regions, but nothing remains of it.28 Tcherny and European travelers in the 19th century observed ruins in a number of places in Georgia, which the local residents identified as former Jewish dwellings.29 Hints of an earlier Jewish presence may also be found in such appellations as Uriatubani ("Jewish neighborhood") and Naurieli ("a place that belonged to a Jew"), applied to a village neighborhood, house, field, cemetery, or even a church 30

Among Georgians, Ebreilidze, which means "Jewish son," is a common family name, and may indicate that these families originated with Jews who were forced to convert. Mamistavalishvili notes the names Uriakopili and Uriakopilishvili which appear in 18th-century documents, as proof of the frequency of conversion by Jews. l

These claims strengthen the assumption that the attenuation of the Jewish community was due in part to the many Jews who converted to Christianity. Yet this information does not elucidate the factors that led to the conversions. Was conversion part of a process of voluntary assimilation and acculturation, or was it the result of persecutions and coercion? Some of the sources mentioned above hint that conversion led to an improvement in the converts' economic and social position. Meanwhile, only minimal evidence has been found indicating that pressure was placed on Jews to convert.

Most writers on the subject of Georgian Jewry accept the view that hatred of Jews such as predominated in other countries hardly existed in Georgia, and that there were always friendly neighborly relations between Georgians and Jews. This opinion was expressed in the writings of prominent Georgian thinkers at the end of the 19th century. It became more widespread during the period of Communist rule, when it was the tendency to blame the Tsarist regime for the blood libels and anti-Jewish riots that occurred during the 19th century.

Aaron Krikheli, in his article on the Jews during the feudal period, supports this view. According to Krikheli, the absence of evidence regarding church incitement against the Jews, or religious persecutions, expulsions or riots, is proof of the tolerant attitude of the Georgian people toward the Jews. Nathan Eliashvili argued that the Georgian people "was by nature a people that loved the stranger, and greeted everyone who came to their land cordially. They felt they had a moral obligation to treat the Jews with honor, since they thought the Bagration family, the royal house so beloved and honored by the Georgian people, was of Jewish origin. Similarly, they knew that these great men, the forefathers and famous people mentioned in the holy writings - Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, David, as well as Jesus and the Apostles, all came from Jewish origins, and that which served as a source of hatred for other peoples in other lands, was in Georgia a source of blessing for the Jews."32 To give added weight to Eliashvili's words, it may be recalled that King David's sling and harp appear on the royal seal of the House of Bagration, and that Moses, and in particular, David, were always figures especially revered in Georgia. The traditions about the Jews who had assisted in the spread of Christianity in Georgia may have also contributed to the Georgian's positive attitude toward the Jews.

The view that the Georgians, in comparison to other nations, excelled in their tolerance of religious minorities, is shared by Western historians. David Lang, for example, claimed that Georgian-style Christianity was never fanatical nor inclined to persecution of others, and treated Moslems and Jews with tolerance.33 Even if these claims cannot be disputed, one must be careful to avoid the tendency to over-idealize. In the descriptions and stories in Tcherny's book there are testimonies one cannot ignore, indicating that there were those among the native Georgians who hated the Jews. Even Eliashvili qualified his own assertion (cited above), stating that in Georgia too, under the influence of the Christian faith, "people began to look upon the Jews as the people who tortured Jesus Christ, and the legends and tales about Jews using Christian blood also began to find a nest in their hearts."34

Under the Tsarist Regime

The annexation of Georgia to the Russian Empire in 1801 had long-term implications for Jewish life, as expressed in changes in the economic and social status of the Jews and in internal developments in their communities. The changes came about very slowly and were hardly felt during the first half of the 19th century. The gradual improvement in the security situation made life easier for itinerant peddlers, but the status of the serfs did not change. The Russian bureaucracy tended not to interfere in the affairs of the princes, and the princes continued to do with their serfs as they wished. When Jews appealed to the authorities for aid and protection against the tyranny of their masters, the officials ruled only rarely that the Jews' complaints were justified. The Jews, along with the other inhabitants of Georgia, were compelled to wrestle with the unyielding Russian bureaucracy, and periodically new difficulties, such as trade restrictions, were placed in their path.35

The implementation of the 1864 decree to free the serfs in Georgia brought no immediate relief. The nobles did not hasten to release the Jews from their obligations, and most of the Jewish population remained severely impoverished.

During the second half of the 19th century, Georgia experienced significant economic growth, which left its mark on the Jews as well. The paving of roads, building of railways, the growth of the Black Sea ports, and initiatives taken to expand local agriculture and industry, together contributed to a burst of commercial development. A class of medium and large merchants grew up among the Jews. They dealt in trade between various parts of the country, also penetrating the field of international trade which was dominated mostly by Armenians.

These developments led to demographic changes. Entire communities left their villages and moved to towns.36 New Jewish communities were founded in the towns of Sukhumi, Poti and Batumi on the Black Sea shore. In Tbilisi, where there had been a very small Jewish community, the population grew significantly. As the century drew to a close, Akhaltsikhe's status as a center of trade with Turkey was impaired, and the Jewish community steadily declined, its members migrating to various commercial centers in the Caucasus, mainly Tbilisi. In contrast, the Jewish community in Kutaisi grew in both numbers and wealth. Some of the biggest merchants in the country were Kutaisi Jews, the most famous being Aaron Eligoulashvili.

The Jews, who at first welcomed the new regime, soon discovered its dark side, its anti-Semitic inclinations. The spirit of Jew-hatred, brought to Georgia by Tsarist officials and by the Russian Orthodox Church which sought to supplant the local church, found an echo among certain local circles; this climate encouraged such manifestations of benighted fanaticism as blood libels. (There is no evidence of blood libels from earlier periods of Georgian history, although they were probably not a totally new phenomenon.) Although most blood libels were not publicized beyond the rural areas in which they occurred, (37) two cases became well-known throughout Georgia and beyond.

In the wake of the blood libel in Surami in June 1850, the local Jewish community appealed for aid to the Jewish community of Istanbul. The case was brought to the attention of Moses Montefiore, who turned to the Russian count Michael Vorontsov, viceroy and governor of the Caucasus, requesting his intervention. Although Voronstov was known as an enlightened governor who contributed much to the development of Georgia, he limited himself to evasive words and efforts to clear the Russian judicial authorities of the charge of perversion of justice.8

The second blood libel occurred in Sachkhere in April 1878. Nine

Jewish peddlers, accused of murdering a Christian girl and using her blood to bake matzot, were put on trial in the Kutaisi district court. The blood libel was widely covered by the Russian Jewish press, arousing feelings of anger and frustration. Prominent Jewish figures, headed by Baron Horace 0. Guenzburg in St. Petersburg, were enlisted by Aharon Eligoulashvili to act in the matter.

Two well-known attorneys, Krupnik, a Jew, and Aleksandrov,

a Russian, were called upon to defend the accused; they succeeded

in refuting the accusations of the prosecution and in acquitting the

defendants.39 This affair, which seemed to signal an intensification of the Russian regime's anti-Semitic policies, evoked much interest among world Jewry, many of whom had been unaware of the existence of the Georgian Jewish community. In Georgia itself, the blood libels incited a wave of anti-Jewish expressions and acts of physical violence.

Another result of the Russian annexation of Georgia was the development of ties between the Georgian and Russian Jewish communities. The 1804 decree that declared the Caucasus to be part of the Pale of Jewish Settlement opened the way for settlement of Russian Jews in Georgia. Jews were attracted to the region by its many economic possibilities and by the pleasant climate.4 The Russian government's attitude toward the settlement of Ashkenazi Jews in the Caucasus was ambivalent. On the one hand, the government was interested in the contribution the newcomers might make, since many of them were skilled craftsmen. On the other hand, the authorities were motivated by their traditional inclination to restrict the area of Jewish settlement, and they were influenced as well by local people who feared Jewish competition. As a rule, instructions to limit Jewish migration came from the Ministry of the Interior in St. Petersburg, while the local authorities in Georgia tried to curtail or cancel these regulations. In 1827, the Ministry of the Interior issued an expulsion order that included not only foreign Jews, but local Jews as well; the speedy intervention of the local authorities prevented the expulsion of the latter. In spite of the decree, the migration of Jews from Russia to Georgia gradually gained momentum. They arrived with temporary residence permits, issued only to professional artisans and specialists who were in demand, and later to former soldiers in the army of Tsar Nicholas I who were allowed to live outside the Pale. Additional expulsion decrees were issued in 1835 and 1847. At mid-century, there were only several dozen Ashkenazi Jewish families in Tbilisi.

In 1852 the government once again allowed Russian Jews to settle in Georgia, although with many restrictions. Nonetheless, the number of Ashkenazi Jews in the country grew steadily. Many Jews arrived without the proper permits and lived in constant fear of expulsion. In 1890 there were some 100 Ashkenazi Jewish families living in Batumi, but only 47 had the proper authorization.41 Most of these Jews made their living as craftsmen. Others were involved in the international oil trade which flourished, as oil reached the town through pipelines from Baku, on the Caspian Sea. Generally speaking, the authorities knew about the families living in Batumi without permits, but they preferred to ignore this fact as long as there were no problems or disorders stemming from economic crises or inter-ethnic tensions.

The situation was similar in other large towns. The Ashkenazi Jews were prominent in professions which contributed to the penetration of Russian-European culture into Georgia. They were pharmacists, physicians, tailors, jewelers, watchmakers and hatmakers, as well as purveyors to the Russian army.

Until the end of the 19th century, few ties were developed between the native Georgian Jews and the Ashkenazi Jewish newcomers. They did not know each other's language, and a wall of exclusivity separated them. The Ashkenazi Jews held the Georgians in contempt, viewing them as primitive and ignorant. The Georgians, in turn, kept aloof from the Ashkenazis, whom they viewed as heretics and transgressors of Jewish law.

In fact, there were only a few Torah scholars among the newcomers. Many had abandoned the traditional Jewish lifestyle. In time, synagogues were established in the towns with large numbers of Ashkenazi Jews, and Talmudei Torah (Jewish religious schools) were also opened. However, there were very few Ashkenazi rabbis, religious teachers and ritual slaughterers to serve the needs of these Jewish communities in Georgia.

Changes and New Trends at the End of the 19th and Beginning of the 20th Centuries

During the second half of the 19th century, Georgian Jewry had ru yet awakened from its state of arrested development. Tcherny, whc traveled through Georgia during the 1860s and 1870s, lamented bitterly that not only had the ideas of the haskalah (Enlightenment and the innovations of the time not gained any foothold, but that the Georgian hakhamim (religious leaders) were ignorant and the community leaders were ineffective. Only at the end of the century did the winds of change begin to have an impact on the traditional lifestyles of Georgian Jews.