קהילת יהודי מץ

עיר בצפון-מזרח צרפת

מספרים על הבישוף סימון, בישוף מץ בשנת 350, שהיה ממוצא יהודי, אולם אין הדבר מלמד על מציאות יהודים בעיר בתקופה מוקדמת כל כך.

אישור ממשי לישיבת יהודים במץ מוצאים רק בסוף המאה ה- 9, במסמך האוסר על נוצרים לסעוד בחברת יהודים.

בתקופת מסעות הצלב היו פרעות גם במץ, ובשנת 1096 רצחו שם 22 יהודים.

בין ילידי המקום היו: רבנו גרשום בן יהודה; מאור הגולה (שהתגורר רוב ימיו בעיר הגרמנית מיינץ, מגנצא במקורותינו), תלמידו אליעזר בן-שמואל וכן ר' דוד בעל התוספות.

מתחילת המאה ה- 13 ועד לכיבוש הצרפתי ב- 1552 לא ניתן ליהודים לשבת דרך קבע בעיר. בסוף המאה ה- 16 כבר הייתה במקום קהילה יהודית של 120 נפש, שחיה בחסות המלך אנרי הרביעי ובחסות יורשיו. עם בואם של יהודים מחבל הריין גדלה הקהילה, ובשנת 1748 מנתה 3,000 נפש בערך.

הקהילה התבססה כלכלית, אך כרעה תחת נטל המסים. יהודים מעטים צברו עושר רב, ואילו המון-העם היה שרוי בדחקות. בעלילת-דם ב- 1670 הוצא להורג הסוחר רפאל לוי.

הרבנים הראשיים היו מתמנים בהסכמת המלך מבין אנשי-חוץ, דוגמת הרב יונה תאומים פרנקל מפראג, הרב גבריאל בן יהודה לייב אסקלס מקראקוב והרב יהונתן אייבשיץ מפראג. הרב הראשי היה גם פוסק בהתדיינות אזרחית בין יהודים, אך במאה ה- 18 תבע הפרלמנט את זכות השיפוט לעצמו, ולשם ערכו במץ, לבקשת הפרלמנט ולשימושו, לקט של מנהגי ישראל (1743).

ב- 1689 הונהג בקהילה חינוך חובה חינם וב- 1764 הוקם דפוס עברי לספרי קודש וחול.

ערב המהפכה הצרפתית פעלו המשפטנים פיירלואי לאקרטל ופייר לואי רדרר להשגת שוויון- זכויות ליהודים. רדרר אף יזם בשנת 1785 תחרות חיבורים מפורסמים באקדמיה של מץ בשאלת היהודים. ב- 1792 העניק לאפאייאט, מפקד צבא המהפכה במץ, חופש דתי ליהודים, אך החופש בוטל בימי הטרור.

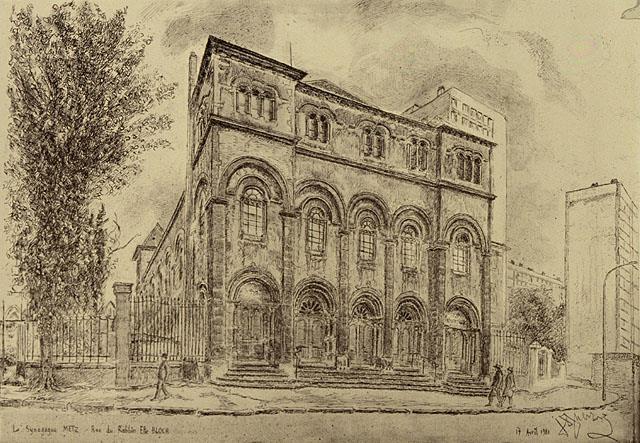

הקונסיסטוריה שהוקמה בסופו של דבר במץ ב- 1808 הקיפה יותר מ- 6,500 יהודים בקהילות האיזור. ישיבת מץ קיבלה מעמד של בית-מדרש ארצי לרבנים ב- 1829, וכעבור 30 שנה הועתקה לפאריס. בית-הכנסת הגדול שוקם מיסודו ב- 1850. עם סיפוח האזור לגרמניה בשנת 1871 עברו כ- 600 מיהודי מץ לצרפת, ובמקומם הגיעו מתיישבים חדשים מגרמניה.

בסיום מלחמת העולם הראשונה, בשנת 1918, חזרה העיר לצרפת והקהילה קלטה המוני מהגרים ממזרח-אירופה ומחבל הסאר.

בשנת 1931 מנתה הקהילה היהודית במץ 4,150 נפש.

תקופת השואה

תחת הכיבוש הגרמני בימי מלחמת-העולם השנייה (1939-1945) הייתה מץ "נקייה מיהודים"; רבים נמלטו בעוד מועד ורבים אחרים, ובתוכם הרבנים בלוך וקאהלנברג, שולחו למחנות.

בית-הכנסת הגדול שימש את הגרמנים כאפסנאות.

אחרי המלחמה שבו יהודים לחיות במץ. ב- 1970 התגוררו בה 3,500 יהודים, מהם כ- 40 משפחות מצפון-אפריקה. יחד עם יישובי הסביבה הקיפה הקונסיסטוריה האזורית 5,500 יהודים. הגדולים שבהם היו: תיוזוויל (450), שארגמין (270), סארבורג (180) ופורבאך (300 יהודים). במץ חמישה בתי-כנסת (מהם אחד לספרדים), תלמוד-תורה, גן-ילדים ואכסנייה לעניים.

שמואל בן ברוך במברג

(אישיות)שמואל בן ברוך במברג (מאות 13-14), רב ומשורר. נולד במץ (כיום: צרפת). במברג למד מאביו, ברוך בן שמואל ממיינץ, ואצל אליעזר בן שמואל ממץ. הוא התגורר בבמברג, גרמניה, נהנה מהערכה רבה ונחשב בר-סמכא בענייני הלכה. רק חלקים מיצירתו הדתית נותרו, והם מעידים על מקוריותו, שהובעה בסגנונו הפשוט. נפטר בבמברג, גרמניה.

מיכאל אבן-ארי

(אישיות)Michael Evenari (1904-1989), botanist, born in Metz, France, of German descent. He grew up as Walter Schwarz in the vicinity of Marburg, Germany, and studied botany at the universities of Frankfurt and Prague, Czech Republic. He carried our research in France, Czechoslovakia and Germany. He became a lecturer at the Technical High School in Darmstadt, Germany, but on account of his Jewishness ancestry he was dismissed from his position in April 1933 without notice. He emigrated to the Land of Israel.

During World War II he served in the Jewish Brigade. When he was demobilized he lectured at universities in the USA and South America.

Evenari was appointed professor of botany at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and then, from 1952 to 1957, he was Dean of the Faculty of Science at the Hebrew University. Between 1953-59 he was vice president of the Hebrew University. In his research Evenari made a significant contribution to the development of farming in the Negev desert in Israel and, at the same time, he greatly increased the knowledge of desert ecology. To this end he studied the farming methods of the Nabateans, Romans and Byzantines. He also studied the influence of red and infra-red light on the germination of seeds an the determination of the food value of algae for livestock and large scale cultivation. He established experimental farms in Shivta and Avdat, Israel, in order to check his findings. In 1977 he was awarded a Honorary doctorate from the Darmstadt Technical High School. In 1988 he was awarded the Otto Ludwig Lange prized for his contribution to productivity and ecology of plants, especially in arid zones. Evenari wrote many articles and a number of books on his expertise and served on several UNESCO bodies.

שלמה בן משה ליפשיץ

(אישיות)שלמה בן משה ליפשיץ (1675-1758) חזן. נולד בפירת, גרמניה, שם היה אביו חזן בשנים 1731-1652. למד בישיבה של דוד אופנהיים במיקולסבורג, ומוסיקה חזנית אצל אביו. הופיע כחזן בקהילות אחדות, וביניהן פראג ופרנקפורט. ב-1715 השתקע במץ. ספרו "תעודת שלמה" (1718) כולל הוראות וצווים מוסריים לחזנים, המובאים במסגרת זיכרונותיו של הסופר. נפטר במץ (כיום, בצרפת).

גליקל מהמלן

(אישיות)When she was aged 14, Glueckel was taken by her parents to the small town of Hameln, near Hanover, to be married to Chaim Segal Goldschmidt, a merchant a few years older than her. The couple lived in Hameln for a year and then moved to Hamburg, where they rented the house that Glueckel would live in until 1700. The couple would enjoy thirty years of happy marriage and fruitful partnership, build considerable wealth, raise twelve children, and arrange for them marriages of wealth and prestige. Glueckel and Chaim worked together running his business trading gold, silver, pearls, jewels, and money. Chaim travelled to England and Russia and throughout Europe selling his goods, with Glueckel advising him on his business dealings, drawing up partnership contracts, and helping keep accounts. As her older children grew up, Glueckel also became involved in arranging their marriages. This meant travel in Germany and abroad, and a fuller understanding of business affairs.

One evening in 1688 while travelling to a business appointment, Chaim fell on a sharp rock. He died several days later. Glueckel found herself responsible for her husband's business as well as for the future of her eight unmarried children. Demonstrating excellent business acumen and a sensible desire to stabilise her financial situation, Glueckel auctioned some of her husband's possessions, paid off his creditors and kept a significant amount for herself and the eight children still living at home. Then she slowly resumed Chaim's trade of pearls. When she saw that the business was successful she expanded it by opening a store. She then started to manufacture and sell stockings, the business began to sell imported and local goods and she began to lend money. She arranged the marriages of all but her youngest child. While expressing a desire to spend her last years in the Land of Israel, she opted instead for security. Her daughter Esther had married Moyse Abraham Schwabe, who lived in the French-controlled city of Metz. At her recommendation, Glueckel moved to Metz and at the age of 54 reluctantly agreed to marry widower Cerf Hertz Levy, a merchant who was wealthier than Chaim had ever been. Levy had seemed an attractive enough prospect: a wealthy businessman and community leader in Metz. Unfortunately, within two years the merchant was bankrupt, losing not only his money but Glueckel's as well. For ten years the merchant tried to recoup his losses, but never successfully. In 1712, Glueckel was again widowed, but this time she was 66 and in poor health. For three years she lived alone in Metz. Finally, she moved in with daughter Esther and stayed there until her death.

In 1690 shortly after Chaim's death, Glueckel began to write her memoirs. The opening words of the memoirs were “In my great grief and for my heart's ease I begin this book the year of Creation 5451 [1690-91] — God soon rejoice us and send us His redeemer! I began writing it, dear children, upon the death of your good father, in the hope of distracting my soul from the burdens laid upon it, and the bitter thought that we have lost our faithful shepherd. In this way I have managed to live through many wakeful nights, and springing from my bed shortened the sleepless hours.” Clearly she considered the memoirs a kind of therapy after her husband's death, and she wished to tell her children (and their children) about her husband, herself, and their families, but she could not possibly have foreseen that they would comprise one of the most remarkable documents of the late 17th and early 18th century. Her memoirs, which describe her life as mother of fourteen children and as businesswoman and trader, has given scholars, students and laymen an invaluable document about Jewish life in Europe in the 17th century. The first five books of the work were apparently completed before her second marriage: she was sad at the loss of her beloved Chaim, but proud of her success at business and marriage arrangements and proud of her children (most of the time). The last two books were written after 1712, when she was again alone and much sadder. Glueckel's story, however, ends happily. She wrote that although she had obviously been loathe to give up her independence and to rely on her children, she willingly agreed to move in with her daughter Esther and son-in-law Moyse in Metz. The memoirs clearly show that as she watched a her children and grandchildren continue to marry well, have children, and prosper Glueckel lived out her remaining years in the shelter of her daughter and son-in-law's evident warm love and respect. As Glueckel put it, she was "paid all of the honors in the world." Most of the narrative ends in 1715, although a few anecdotes continue to 1719.

The original Yiddish manuscript of Glueckel's book is lost, but copies were made by one of her sons and by a great-nephew, and from these her work was published in 1896 as "Zikhroynes Glikl Hamel".

שמואל בן ישראל היילפרין הלמן

(אישיות)שמואל בן ישראל היילפרין הלמן (1675- 1785), רב, נולד בקרוטושין, פוליןץ אחרי לימודיו בפראג מונה לרב של קהילת קרמסייר, מוראביה (1720 - 1726) ואח"כ לרב קהילת מנהיים (1726-1751), שם הוא יסד ישיבה. בשנת 1751 הוא החליף את ר' יונתן אייבשיץ בקהילת מץ, ונשאר שם עד סוף ימיו. הוא היה מהמתנגדים החריפים של תנועת השבתאות, ובעת כהונתו במץ מצא שם חמישה קמיעות שנכתבו על ידי ר' יונתן אייבשיץ, שחיזקו את חשדו שאייבשיץ היה שבתאי בסתר, ויחד עם שני רבנים אחרים הטיל חרם על אייבשיץ. הוא היה מחברם של אוצרות מילים לתלמוד.

לזר איזידור

(אישיות)Lazare Isidor (1814-1888), rabbi, born in Lixheim, Lorraine, France, who became Chief Rabbi of France in 1867. Isidor was born into a rabbinical dynasty dating back to the fifteenth century in Hesse-Nassau and Alsace, and which one of the most famous was his great-grandfather Naphtali Hirsch Katzenellenbogen.

He played an important role in the integration of the Jewish community in French civil society, first by initiating a new translation of the Hebrew Bible into French, which became the official Bible of the French Rabbinate, and the other, with the help of Adolphe Cremieux, in obtaining the abolition of the infamous oath "Judaico more" which Jews were forced to pronounce in a synagogue before giving evidence in a civil court. During his time at Pfalzburg he refused to allow a member of the congregation of Saverne to pronounce this oath, considering it an insult to his coreligionists. Isidor was prosecuted for his direction and brought to trial. After his acquittal the decree establishing the oath, the last measure against the Jews of France, was cancelled by a decision of the Court of Cessation.

In 1829 Isidor entered the rabbinical school of Metz, which a short time later became the Central Rabbinical School of France under government supervision. In 1837 he was appointed rabbi of Phalsbourg, a position he held for ten years. In 1844 Isidor went to Paris, where he was received with enthusiasm, and in 1847, at the early age of thirty-three, became Chief Rabbi of Paris, a position which he occupied for twenty years. In 1867 he became chief rabbi of France.

Thanks to his reputation and his personality he was able to maintain the unity of the community and to persuade some congregations to drop their demands for reform of the ritual. Isidor was also active in bringing the Algerian Jewish community under the umbrella of the French chief rabbinate.

גבריאל בן יהודה אסקלס

(אישיות)

Jacob Ben Joseph Reischer

(אישיות)Jacob Ben Joseph Reischer (also kbown as Jacob Backofen) (c. 1670-1733), rabbi, halakhic authority, and author, born in Prague, Czech Republic (then part of the Austrian Empire). He studied under Aaron Simeon Spira, rabbi of Prague, and was known as a prodigy in his early youth. Afterward he studied under Spira’s son, Benjamin Wolf Spira, av bet din of the Prague community and rabbi of Bohemia, whose son-in-law he subsequently became. His brothers-in-law were Elijah Spira and David Oppenheim. Reischer’s surname, born by his grandfather and uncles (see introduction to his Minhat Ya’akov, Prague, 1689), derives from the fact that his family came from Rzeszow, Poland, and not, as has been erroneously stated, because he served as rabbi of that town.

While still Young, he became dayyan of the “great bet din of Prague.” He was appointed av bet din of Ansbach, Bavaria, and head of its yeshiva in 1709, and in 1715 av bet din of Worms. There, students flocked to him from all parts of Europe. He had, however, opponents who persecuted him. About 1718, he was appointed av bet din and head of the yeshivah of the important community of Metz. There, too, he did not find peace. He related that in 1728 “malicious men, as hard as iron, who hated me without cause, set upon me with intent to destroy me by a false libel, to have me imprisoned.” His first work, Minhat Ya’akov, was published, while he was still young, in Prague in 1690. In the course of time he was accepted by contemporary rabbis as a final authority (Shevut Ya’akov vol. no. 28; vol. 3, no. 61), and problems were addressed to him from the whole Diaspora, e.g. Italy, and also from Erez Israel (ibid., vol. 1, nos. 93 and 99) He made a point of defending the Rishonim from the criticism of later writers, and endeavored to justify the Shulhan Arukh against its critics. But there were also those, particularly among the Sephardi rabbis of Jerusalem, who openly censured his habit of criticizing Rishonim and Aharonim (ibid., vol. 1, no. 22), and criticized him in their works. His replies to those criticisms were not always couched in moderate language (see Lo Hibbit Aven be-Ya’akov). The main target of his criticism was Joseph b. David of Breslau, author of Hok Yosef (Amsterdam, 1730).