The Jewish Community of Atlanta

Atlanta

Capital of the State of Georgia, USA.

As of 2010, Atlanta's Jewish population was estimated at 120,000, making it the ninth largest Jewish community in the United States, in spite of the fact that its Jewish community is relatively young. According to the 2006 population study conducted by Jacob Ukeles and Ron Miller for the Jewish Federation of Greater Atlanta, children under age 18 comprise as much as 25 percent of the community, while Jews aged 65 and over represent only 12 percent. The vast majority (81 percent) of Atlanta's Jewish residents were born outside the state of Georgia. Of this group, approximately 30% are transfers from New York and New Jersey and about 6% were born in the former Soviet Union. While Atlanta's Jewish population is predominantly Ashkenazi, its Sephardi community is one of the largest in the country.

Nearly every national Jewish organization has a branch in Atlanta. There are numerous institutions serving the Jewish community's social, educational, and cultural needs. More than 60 different agencies are partnered with the Federation of Greater Atlanta, the community's principal welfare organization. With a $125 million endowment, the Federation is also one of the largest sources of funding for Jewish programs.

In addition to being the state's capital, the city of Atlanta serves as the country's southeastern headquarters for several major organizations, including the American Jewish Committee, B'nai B'rith, the Anti-Defamation League, the Council of Jewish Federation and Welfare Funds, and the National Welfare Board. Atlanta is also one of 10 locations in the United States with an Israeli consulate general.

Atlanta has a variety of kosher restaurants and food options, as well as its own kashrut commission, the AKC (Atlanta Kashrut Commission), an agency which certifies over 100 companies, supermarkets, restaurants, and food manufacturers in Atlanta and throughout the United States. By 2015 there were 24 kosher establishments in the Greater Atlanta area, including bakeries, butcher shops, catering companies, and restaurants. There are also several grocery stores which carry kosher food products.

By 2005, there were 34 synagogues in Greater Atlanta, an increase from the 19 that existed in 1984. Nonetheless, the vast majority of the Jewish community is unaffiliated; 42% of Atlanta's Jews belong to a synagogue or Jewish organization –one of the lowest rates in the United States. Among those affiliated with a congregation or connected to the Jewish community, 46% identify as Reform, 26% as Conservative, and 9% as Orthodox. The Chabad-Lubavitch movement has established a presence in Atlanta, and has made efforts to reach out to the more than 70,000 unaffiliated Jews in the community.

Several Atlanta neighborhoods have their own eruv, including Toco Hills, Sandy Springs, Dunwoody, and Alpharetta in the north metro area. There are also five congregations that have their own mikvah. In 2015, Congregation B'nai Torah opened a new mikvah facility which is used both by many in the community, as well as by people from other Jewish communities.

The Jewish community of Atlanta has established many educational programs and institutions for Jewish youth. The Marcus Jewish Community Center of Atlanta (MJCCA) offers a variety of programs, as do many of the community's congregations. Jewish education is also often part of many of the community's social and cultural associations; there are more than 15 after-school programs and summer camps.

Jewish schools in Atlanta range from Orthodox to Reform. There are seven preschools, five day schools, and four high schools. One of these high schools is Atlanta Jewish Academy, the result of a 2014 merger of Greenfield Hebrew Academy (GHA), and Yeshiva Atlanta (YA), the oldest Jewish day schools in Atlanta. Other notable Jewish schools include the Torah Day School of Atlanta, the Davis Academy, the Solomon Schechter School of Atlanta, the Doris and Alex Weber Jewish Community High School, and Temima High School, an Orthodox girls' school.

The Jews of Atlanta are widely spread out over the city. Many have moved to the northern, southern, and eastern parts of the city. But while there is no predominantly Jewish neighborhood, there are several areas with a significant number of Jewish residents. Dunwoody, East Cobb, Sandy Springs, Alpharetta and Toco Hills have sizeable Jewish communities. The city's downtown area has become a hub for young Jewish professionals, as well as for young families. In order to keep the community socially and culturally connected, many Jewish institutions and agencies have opened branches in the suburbs.

Many in Atlanta's Jewish community have been recognized for their philanthropic endeavors. Several community projects have been developed under Jewish leadership and with significant donations made by Jewish entrepreneurs. Individuals such as Arthur Blank and Bernard Marcus, the founders of Home Depot, are well-known for their philanthropy as well as for their business activity.

There are multiple sites of Jewish historical significance in Atlanta. The William Breman Jewish Museum provides a history of Atlanta's Jewish community, and offers permanent exhibits dedicated to the Holocaust. Other important sites include memorials commemorating the Holocaust and the events of World War II. Located in the Greenwood Cemetery is a large granite monument, featuring six torches, each one representing one million Jews who perished in the Holocaust. The memorial was placed there by the Eternal-Life Hemshech organization, which was formed in 1964 by Holocaust survivors living in Atlanta. In 2008, the memorial was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Also located in Greenwood Cemetery is a memorial to Jewish war veterans. The Jewish Community Center's Zaban Park is home to the Besser Holocaust Memorial Garden. Each year the garden hosts ceremonies commemorating the Holocaust and Kristallnacht.

The primary Jewish publication in the city is the Atlanta Jewish Times (AJT), originally known as the Southern Israelite. Distributed for free, it serves the Jewish community of Atlanta and adjacent areas. Before World War II, there were three English-language Jewish newspapers, as well as a Yiddish newspaper.

HISTORY

German Jews lived in the area, an important transportation center, beginning in the early 1840s. The first known Jew to live in Atlanta was Jacob Haas, who opened a dry goods store with Henry Levi in 1846. Moses Sternberger, Adolph Brady, and David Mayer arrived in the city shortly thereafter, as did Aaron Alexander and his family, who were American-born Sephardim from South Carolina. Atlanta's first Jews were mostly merchants. Some were involved in financial services such as banking, brokerage firms, insurance, and real estate. Others manufactured paper products and cotton bagging.

The Hebrew Benevolent Society, established in 1860, later became the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation in 1867. Still later it was known simply as "The Temple." The Temple was Reform; its first rabbi, Rabbi Dr. David Burgheim, was appointed in 1869, and the building housing the congregation was erected in 1877. Eastern Europeans who emigrated to Atlanta in the 1880s established an Orthodox congregation, Ahavath Achim, in 1887 and built a building for the synagogue in 1901. There were three more Orthodox congregations by 1910, and Sephardim from Rhodes founded a congregation in 1914.

Since the post-Civil War era Jews have been active in Atlanta politics. Samuel Weil served in the Georgia Legislature in 1869, Aaron Haas became the city's mayor pro term in 1875, and Sam Massell was elected mayor in 1970. David Mayer, the founding member of the Board of Education, is remembered as the "father of public schools." Jews are also among the founders of the city's hospital, library, chamber of commerce, and other public institutions. Rabbi Dr. David Marx, the rabbi of The Temple for 51 years, was known for his interfaith leadership; his successor, Rabbi Dr. Jacob M. Rothschild, is known for his efforts advocating for racial equality. Rabbi Tobias Geffen was an Orthodox rabbi who was a major figure within the community for the fifty years he served there. Among his more notable actions was giving a hekhsher (kosher certification) to Coca-Cola, an Atlanta-based company.

While the elite Jews of Atlanta had assimilated into the city to an unusual degree, they nonetheless felt detached from the rest of Atlanta society. They began to feel truly threatened by anti-Semitism during the Leo Frank case of 1913-1915. Frank, a respected member of the community, was convicted of the murder of a 13 year old girl and sentenced to hang. When his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by Governor John Slaton, who was deeply skeptical of the conviction, a mob kidnapped Frank from prison and lynched him. Frank's trial and lynching had a deep impact on the Jewish community, many of whom tried to hide their Jewishness or moved out of the city altogether. Leo Frank's case was also mentioned in the announcement of the creation of the Anti-Defamation League in 1913. Most historians conclude that Frank was innocent, and The Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles officially pardoned Frank posthumously in 1986.

1958 saw another outbreak of violence against the Jewish community when The Temple was bombed by white supremacists, who were angered by The Temple's support for civil rights.

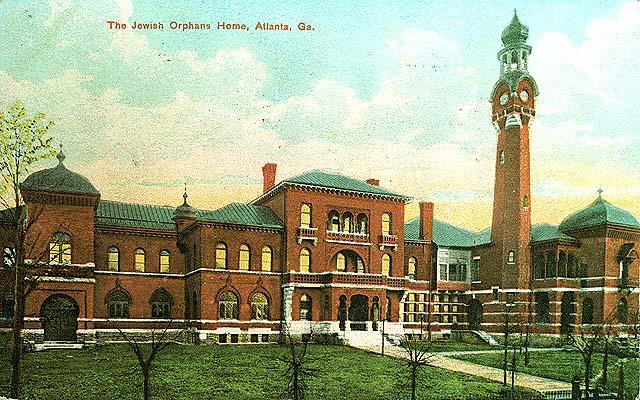

Jewish communal institutions entered a peak period of development during the turn of the 20th century. The early 20th century saw the establishment of institutions including: a Jewish Community Center, the Bureau of Jewish Education, Hebrew day schools, a home for the elderly, and "The Southern Israelite."

The Jewish community in Atlanta numbered approximately 28,000 in 1980; by 2006 it had grown to over 120,000.