The Jewish Community of Ostrava Moravska

Ostrava Moravska

German: Ostrau

A city in the northeast Czech Republic. The capital of the Moravian-Silesian Region

Ostrava is located near the Polish border, where the Odra, Opava, Ostravice, and Lucina Rivers meet. It is the third-largest city in the Czech Republic. Until 1918 Ostrava was part of the Austrian Empire. During the interwar period, and from the end of World War II until 1993, it was part of the Republic of Czechoslovakia.

One of the Torah scrolls sent from Ostrava to the Central Jewish Museum in Prague during World War II is currently located in the Kingston Synagogue in the United Kingdom.

HISTORY

A few protected Jews (those who were shielded by the local nobles in exchange for taxes and other services) were living in Ostrava by 1508, but the general Jewish population was not permitted to settle in the city until after the emancipation of Jews throughout the Austrian Empire in 1848, and the subsequent removal of residence restrictions. Until then there were a small number of Jews living in the town, both legally and illegally. In 1792, after Emperor Joseph II issued the Tolerance Edict in 1782, a Jewish man named Mordehai Schoenhoff settled in the town and rented a wine store. Later a few Jews arrived from Hotzenplotz, Leipnik, and Ungarisch-Brod. During the first half of the 19th century Jews from Silesia, Moravia, Slovakia, and Galicia began to settle in Ostrava. Those who came to Ostrava from the east tended to be more religious, and the community that they established was more traditional; it was these Galician arrivals who established a mikvah (ritual bath) and an Orthodox synagogue.

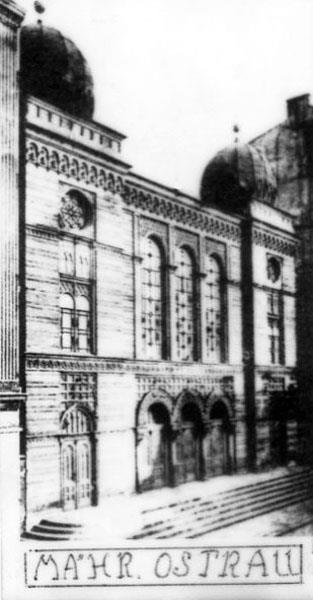

Once Jews were allowed to freely settle in the city, communal life began to flourish. A synagogue was built in the Polish part of the town in 1857. A Tarbut society was established in 1860 and led by Shimeon Fraenkel. That year also saw an influx of Jews after Ostrava was ordered by the emperor to remove any remaining residence and economic restrictions on the Jews. A Jewish cemetery was consecrated in 1872, following a cholera epidemic. From 1860 until 1875 the Jewish community was made up of Jews from Moravska Ostrava and the neighboring Polska Ostrava (German: Plnisch-Ostrau). Beginning in 1875, however, the Jewish community of Moravska Ostrava became independent. A community committee was subsequently established, led by Berthold Schwartz, and replaced Tarbut. Marcus Strassman was appointed as the community's leader, with Dr. Joseph Wachsberg acting as his deputy. A new synagogue was consecrated in September 1879, with thousands of people in attendance.

In 1881 the community numbered 700 members. During this period at the end of the 19th century, Ostrava became known as the "Moravian Manchester," due to its increasing importance as an industrial center. The Rothschild and Gutmann families, in particular, owned important coal mines and ironworks in the area. This brought Jews to the city from all over Moravia and Galicia; by 1890 the Jewish population had reached 1,356 and in 1900 the Jewish population was 3,272.

A number of synagogues were built in Ostrava's suburbs in order to accommodate the influx of Jews; an Orthodox synagogue would later be added to the rest in 1926 and the city would ultimately be home to six synagogues. Rabbi Dr. Bernhard Zimmels, the community's first rabbi, was appointed in 1890. Rabbi Zimmels passed away in 1893 and was succeeded by Dr. Yaakov Schapira in 1903. Marcus Strassman, the first leader of the community, was succeeded by Dr. Alois Hilf after his death.

Communal institutions included an old age home, a Bikkur Holim, a women's society, a home for children, and a Bnei Brith lodge. A Hebrew school was established in 1863; it was officially recognized by the authorities as an elementary school in 1884, the same year that the language of instruction was changed to German (the school's language of instruction would eventually be changed to Czech, after the establishment of the Republic of Czechoslovakia); Hebrew was taught for 2 hours each day. By the end of the 19th century the school enrolled 303 students, and had 7 classes. There was also a vocational boarding school affiliated with the metal industries of the Austrian branch of the Rothschild family, which attracted students from all over the Republic of Czechoslovakia. A summer camp for Jewish children was established in 1912.

In 1918 Dr. Reuben Faerber established a publication and sales company; most of the published books dealt with Jewish and Zionist subjects. During the interwar period Julius Kittels Nachfolger published a German translation of the Talmud.

The Republic of Czechoslovakia recognized the Jews as a national minority with concurrent rights, prompting Jews throughout the country to become active Zionists, as well as to take an active role in local politics. The Jews of Ostrava obtained 60 seats in the town council in 1921, including representatives from the Jewish Democrats, the Zionist Party, Jewish Laborers, and Jewish Czechs. In 1931 the first Jewish Party conference was held in Ostrava, and in 1935 Ernst Fisher was elected as the party's representative in the Senate. Dr. Alois Hilf was the president of the Federation of the Jewish Communities of Moravia in the National Jewish Council. Dr. Zigmund Witt was a member of the Senate while Dr. Victor Haas was a member of the Parliament.

Many members of the community were active Zionists; in fact, beginning in 1921 the executive committee of the Zionist organizations of Silesia and Moravia was located in Ostrava. Many Jews in the city contributed generously to Keren HaYessod. Jewish students worked to spread Zionist ideology, particularly among the youth. Zionist organizations held their conventions in the city and a branch of the Palestine Office was opened. Zionist groups that were active included Poalei Zion, Achdut HaAvodah, Mizrachi, Revisionist Zionists, HeHalutz, HaShomer HaTzair, HeHalutz HaKlal Zioni, Blau Weiss, Maccabi, as well as a number of others. Kedmah, a group to prepare young Jews to emigrate to Mandate Palestine, was established in 1924. Community members bought membership and voting rights before the 15th Zionist Congress, as well as in subsequent years; 518 Jews from Ostrava participated in the elections to the 20th Zionist Congress.

In 1931 there were 6,865 Jews (5.4% of the total population) living in Ostrava.

Among the notable figures from Ostrava were the playwright and poet Marcel Meir Faerber, who later became a journalist and wrote for the Tribuna in Bratislava and Yediot Khadashot in Israel. Joseph Wechsberg, a writer and literary critic, as well as the editor of the Jewish weekly Selbswehr (published in Prague), was born in Ostrava in 1907.

THE HOLOCAUST

Following the Munich Agreement of September, 1938, which dissolved the Republic of Czechoslovakia and annexed the Sudeten Region to Nazi Germany, Ostrava absorbed waves of Jews fleeing from the region. In March, 1939 however, the region of Bohemia and Moravia became a protectorate of Nazi Germany, ushering in a period of discrimination and violence against the area's Jews. Ostrava was the first city to be occupied by the Nazis, who burned the city's six synagogues. The city's Jews began to be deported soon after; the first transports took Ostrava's Jews to Poland, while later transports sent them to the Terezin (Theresienstadt) Ghetto. From these locations they were sent to concentration and death camps, where most perished.

Before the deportations began, 348 ritual objects, 680 books, and 246 documents from Ostrava's Jewish community were sent to the Central Jewish Museum in Prague.

POSTWAR

Approximately 250 survivors returned to Ostrava after the war and reestablished a Jewish community. Eventually the communities of Bohumin, Karvina, Krnov, Opava, Prlava, and Olomouc became affiliated with Ostrava's Jewish communit; the entire community consisted of 500 Jews. Ostrava had a cantor, while the regional rabbi, Rabbi Dr. Richard Feder, lived in Brno. 649 Jews lived in Ostrava, 548 of whom were officially registered in the community.

A new cemetery was established in 1965. The old Jewish cemetery was destroyed during the 1980s and the remaining tombstones were transferred to the cemetery in Silesian Ostrava.

In 1997 the Jewish community of Ostrava had 80 members.

Yehudah Bacon

(Personality)Yehudah Bacon(1929- ), painter, born in Ostrava, Czech Republic (then Czechoslovakia). During World War II, he was deported to Nazi concentration camps where he was held between 1942-1945, and was later sent on the "death march" to Mauthausen, where he was liberated.

In 1946 he was taken to the Land of Israel by Youth Aliyah and studied at the Bezalel School of Art, Jerusalem. Bacon became head of the department of etching and lithography at Bezalel. He focused on graphic work, but turned to a variety of media including oils, watercolors, and inks. The horror of the Holocaust was present in his work, tempered by faith in humanity. His later work, however, had a gentle, romantic quality. He was a witness at the Eichmann Trial in Jerusalem, and the Auschwitz Trial in Frankfurt.

Yehudah Bacon participated in many Group Exhibition and held Solo Exhibitions in Israel, South Africa, the U.S., Germany, Finland, and Prague.

Artur London

(Personality)Artur London (1915-1986) Politician. He was born in Ostrava, Czech Republic (then part of the Austria Hungary Empire) and in 1937 went to Spain where he joined the Communists in the International Brigade fighting in the Civil War. After the defeat of the Republicans in 1939 he moved to France and in 1940 was arrested by the Germans and sent to Buchenwald concentration camp. London returned to France after the war and then became a leading figure in the Czechoslovak Communist Party in Prague. In 1948, he was appointed Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs. In 1951, he was arrested and was one of the accused at the Slansky trial where he was charged with being a Zionist and a Trotskyist. Sentenced to life imprisonment, he was released in 1955 and later rehabilitated. In 1963 he moved to France where he published L'Aveu, about the Slansky trial. It was filmed by Costas-Gavras with Yves Montand depicting the hero based on London.

Josef Rufeisen

(Personality)Josef Rufeisen (1887 – 1949) Zionist. When he was age 14 he founded a Zionist society among high school students in his native Ostrava and while a law student in Vienna was active in student Zionist societies and for a time headed HaKoah the Austrian Zionist sports association. After his studies, he returned to Ostrava where he practiced law. After World War I he participated in the establishment of the Jewish National Council in Czechoslovakia and during the interwar period chaired the Czech Zionist territorial federation, whose headquarters, because of Rufesien, were transferred to Ostrava. In 1938 he settled in Tel Aviv where he was president of the Association of General Zionists and of the Association of Czechoslovak Immigrants.

Jacob Bornfriend

(Personality)Jacob Bornfriend (born Jakub Bauernfreund) (1904-1976), painter, born in Zborov, Slovakia (then part of the Austria-Hungary, later in Czechoslovakia), one of seven children of a poor Jewish family. He spent his early years in Ostrava, Czech Republic, and Bratislava, Slovakia, where he worked as a retoucher of pictures.

He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague in 1929. In 1939 he immigrated to England and changed his name from Bauernfreund to Bornfriend. He spent four years working in factories before he could return to painting.

Bornfriend painted in oils, pastel, gouache, collage and worked in the graphic arts. He was a well respected artist within the Jewish Community. His style was basically expressionist, influenced to some extent by cubism. His first Solo Exhibition in London took place in 1950. He also exhibited at Prague, and Gothenburg, Sweden.

Hans Moller

(Personality)Hans Moller (1896-1962), textile industrialist, born in Vienna, Austria. He was forth generation of textile industrialists. The Moller Family owned the cotton-spinning mill, founded in 1865 by his great-grandfather, Simon Katzau in Babi, Bohemia (now in Czech Republic). Hans Moller, together with his cousin, Moller Erich (born in Ostrava, Moravia, 1895) went to Mandatory Palestine in 1933 and in 1934 founded Ata Textile Company at Kiryat Ata (then named Kfar Ata). They finally settled in Mandatory Palestine in 1938. This was the first integrated cotton, spinning, weaving, dyeing, and finishing plant in the country, manufacturing and retailing ready-to-wear clothing and supplying the Allied forces in the Middle East during World War II. Originally a family business, Ata became a public company. In 1967 it had 1,861 employees. In 1948 a subsidiary company, Kurdaneh Textile Works Ltd., was founded. Erich left Ata in 1949 to build Moller Textile Ltd., a spinning, twisting, and dyeing plant in Nahariyah. Both plants have made major contributions to Israel export.

Stella Kadmon

(Personality)Stella Kadmon (1902-1980), actress, singer, born in Vienna, Austria (then part of Austria-Hungary). She studied acting from 1920-23 at the Vienna Academy of Music at the Volksoper. Her acting career began at the Landestheater in Linz. In 1924-1925 she appeared with the German Theater of Ostrava, Czech Republic (then in Czechoslovakia). Later she studied acting and directing with Armin Seydelmann and Max Reinhardt. In 1926-31 she performed as cabaret singer in Munich, Vienna, Berlin and Koln. She was co-founder, with Peter Hammerschlag and Gerhart Hermann Mostar, of the political, critical cabaret Der liebe Augustin, in Vienna, in 1931.

Following the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938, the new regime closed down the cabaret. Later in the year, with the aid of the German ambassador, Stella Kadmon fled to Belgrade, Yugoslavia, where she stayed with relatives. She immigrated to the land of Israel in 1939. She was director of the English-language Cabaret Papillion in Tel-Aviv from 1940-1942. In the following years Kadmon, with Arnold Chempin and Karl Guttmann, organized evenings of chansons and dramatic readings. Due to a ban under the British mandate, public performances of German authors was interdicted. They were compelled, consequently, to perform in private clubs. Their productions included Franz Werfel’s Jacobowsky und der Oberst and Bertolt Brecht’s Frucht und Elend des Dritten Reiches. Kadmon was also active in cultural programs of the Free Austrian Movement in Palestine.

In 1947 Kadmon returned to Vienna. She became director of Der liebe Augustin, which had reopened in 1945. In 1948 the cabaret changed to theatre performances. It took the name Theater der Courage, in which avant-garde plays were performed. Stella Kadmon staged numerous Austrian and world premieres of plays by Wolfgang Borchert, George Roland, Adolf Schutz, Ferdinand Bruckner, Jean Anouilh and others.

Kadmon was awarded the Honorary Silver Medal of the City of Vienna, in 1968, and the title of Professor in 1977. She also received many prizes for her work in staging. She died in Vienna in 1989.

Karl Farkas

(Personality)Karl Farkas (1893-1971), comedian, actor, director, and scriptwriter, born in Vienna, Austria (then part of Austria-Hungary). He received his acting training at the A.M.d.K. in Vienna during 1913-1914. In World War I he served in the Austrian-Hungarian Army, for which he received seven decorations. Farkas started his acting carrier in Olomouc and Ostrava, then both in Czechoslovakia, and in Linz, Austria. In 1919, he became stage director with the Landestheater in Linz. He was actor and director at the Neue Wiener Buehne, Vienna, from 1920 to 1926. At the same time he was cabaret author for Viennese cabarets. Together with Fritz Gruenbaum, he developed the concept of double emcee (comic team). Farkas was the creator of the Wiener Revue. From 1926 until 1931 he served as head of the Wiener Stadttheater. He appeared as guest performer at theaters in Vienna and abroad. He wrote and produced various revues, and also worked as scriptwriter in Hollywood. In 1932-1933 he was head of the Revubuhne Casino, Vienna, and carried out guest tours with Gruenbaum, which included Prague in 1933. Farkas became head manager of the Viennese cabaret Simpl.

In the spring of 1938, following the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, he was arrested. After his release he immigrated to France via Czechoslovakia. In France, in 1938-1939 he served as head of cabaret Imperatrice. He organized cabarets, including with Oskar Karlweis, La gaite de Vienna au coeur de Paris, and also produced guest appearances in the Netherlands. In 1939 he became member of Societe des Autheurs et Compositeurs Dramatiques. Farkas was interned at Gurs concentration camp in 1940, but in 1941 he managed to reach the USA. In New York he worked to establish cabarets, with Kurt Robitschek, among others. He appeared at theaters including the Majestic Theater, New York, in radio broadcasts for Austrian Action and for O.W. I. He was very successful in the Broadway musical Marinka. Farkas spent the war years in America. In 1946, a year after the end of World War II, he returned to Austria, and resumed his artistic carrier in Vienna in theater, film, radio, TV, and cabaret. He contributed to the Wiener Kurier and other journals. From 1946 till 1971 he was head of the new Simpl, Vienna.

In 1956 he was honored with the Goldenes Ehrenzeichen fur Verdienste um die Republik Osterreich, in 1963 with the Ehrenmedaille der Stadt Wien in Gold, and in 1965 he received the title of professor.

His works include Zuruk in Morgen, Also sprach Farkas and Farkas entdeckt Amerika. He also wrote a number comedies and revues, among them Wien gib acht, Die Wunderbar, Bei Kerzenlicht and Traumexpress.

Bohumin

(Place)Bohumin

Novy Bohumin is part of Bohumin

In German: Oderberg or Neu Oderberg

A town in Karviná District in the Moravian-Silesian region of the Czech Republic in the historical region of Silesia. Untill 1918 the District of Teschen was part of Austria-Hungary and after World War I it was annexed to the Czechoslovak Republic.

21ST CENTURY

As a monument to the murdered Jews, a memorial to holocaust victims was unveiled in 2004 at the Place of the Future. The memorial was damaged several times by anti-semitic symbols. In 2007 the remaining Jewish cemetery was revived which was almost completely devastated by the Nazis during the war. 40 gravestones were restored, however, two weeks after the restoration 25 were destroyed.

HISTORY

In 1655 a local noble allowed two Jews to settle in his estates and by 1751, six Jewish families lived in the estates of Oderberg. In the 19th century many Jews came to this town, which was situated on the border to Poland. Later they established there distilleries. At the beginning the Jews belonged to the Jewish community of Teschen, later to the community of Ostrava in Moravia. In 1898 a section in the general cemetery was allocated to the Jewish community. A synagogue was established in 1900 and the community was recognised as an independent community in 1911. The town had a Jewish elementary school. Among the institutions of the community were a hevra kaddisha (burial society), women’s society and bikkur holim. In 1921 the community numbered 1900 Jews. At this time Joseph Zanker was the chairman of the community and Dr. Ernst Bass the rabbi. In 1924 a community center was opened. The language of the Jews of Bohumin was German.

The first two Jews in Bohumin were producers of soap and hard liquor. Later the main occupation of the Jews were commerce and crafts. In the 2nd half of the 19th century, when the Jews obtained civil rights (1848), they were accepted in all spheres of the economy and society, including the professions and art. The Jewish poet Arthur Zanker (1890-1957) was born in Bohumin.

In the Czechoslovak Republic, between the two world wars, the Jews were recognised as a national minority with full rights. Numerous Zionist activities were held in the town. The Jewish youth movement Maccabi was active. In 1926-1927, prior to the 15th Zionist Congress, 230 Shekels (membership and voting rights to the Zionist Congress) were purchased. In 1933 a Maccabiah was held in Bohumin with many participants. The same year a Jewish association for winter sports, headed by Dr. Paul Maarz of Bohumin was established. In the elections to the 20th Zionist Congress (1937) 117 persons of the community took part. 52 voted for the General Zionists, 44 for Poalei Zion, 16 for Hamizrahi, 2 for the National Jewish Party and 3 were against the partition of Palestine. A Plugat Hakhshara of Kibbutz Maapilim was at Bohumin.

In 1930, 984 Jews lived in the jurisdiction area of Bohumin, and in the town itself 722 (6.6% of the population).

THE HOLOCAUST

Following the September 1938 Munich agreement, about a year before the outbreak of World War II, the Czechoslovak Republic was dismembered. The Sudeten region was annexed to Nazi Germany and the district of Teschen was given to Poland. In September 1939, with the occupation of Poland by the German army, the district of Teschen too became occupied territory. On Rosh Hashanah 5700 (1939) the synagogue of Bohumin was set on fire and the building was destroyed. The Jews of the town were taken to build a bridge that had been bombed by the Poles. They were then expelled to a concentration camp in Nisko, close to Lublin. Most of the community members perished in the course of the war.

After the war the district of Teschen was returned to Czechoslovakia. The remaining Jews returned to the town. In 1948 there were 57 Jews, 53 of them registered in the Jewish community. A prayer house was founded. Several years later the community ceased to exist and the building of the prayer house was turned into an arts and music school. The funeral house in the Jewish section of the cemetery was handed over to the Christian sect of the Guardians of the Seventh Day.

Opava

(Place)Opava

In German: Troppau

A city in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. Beginning in 1742 Opava was the capital of Austrian Silesia. Between 1918 and 1928 it was the capital of Czech Silesia.

21ST CENTURY

There is a Jewish cemetery with a number of gravestones that have remained standing.

HISTORY

Opava was founded in 1224 and Jews are recorded in Opava from 1281. During the Middle Ages there was a well-organized community, and Jewish homes and synagogues were located in Na Valech Street.

The Jews were expelled from Opava at an unknown date, but were allowed to return and reclaim their homes in 1501. Subsequently, the Jews of Opava were once again forced to leave in 1523, after Jews were expelled from Silesia.

By the beginning of the 19th century several Jewish families had returned to Opava. Their number increased after 1848, when Jews throughout the Austro-Hungarian Empire were granted full civil rights. In 1867 there were 134 Jews living in Opava.

A prayer house was opened in 1850, and a synagogue was consecrated in 1855. A new synagogue was built in 1896, after which the old synagogue was turned into a high school.

The community’s first cemetery was consecrated in 1850. Then, in 1854, a new cemetery opened and the graves and tombstones were transferred from the old cemetery to the new. The new cemetery served the community until 1892. A third cemetery was opened later.

At the end of the 19th century Opava became a center of German nationalism, and the community was subjected to antisemitic attacks.

During the interwar period, Dr. Shimeon Friedman served as the community’s rabbi, and Gustav Pinci was the head of the community. Opava’s Jewish community was officially recognized by the government in 1923.

Community organizations included a chevra kaddisha, a women’s society, a Bnai Brith lodge, and a literature society. A Jewish theater group visited Opava in 1925.

Rabbi Friedman was an enthusiastic Zionist, and organized a community library on Jewish subjects. Other Zionist organizations and activities included the Zion Association, which was active in Opava even before World War I (1914-1918). After the war, during the period of the Czechoslovak Republic, which granted its Jews national and cultural autonomy, the community became increasingly active in the Zionist movement. Gustav Pinci was elected to the central committee of the Zionist organization at the first Zionist Convention in Czechoslovakia in 1919. Komorau, the agricultural training program that was organized in Opava, became the center of the HeHalutz movement. Other active Zionist organizations included Mizrahi, and a Jewish sports club, which was founded in 1902 and affiliated with the Maccabi sports movement in the 1920s. In 1926, prior to the elections for the 15th Zionist Congress, the Jews of Opava paid 430 Shekels, granting them membership and voting rights. 173 members of the community voted in the elections to the 20th Congress in 1937. In March 1938, during the regional Zionist convention, two members of Opava’s Jewish community, Dr. Paul Hesslein and Dr. Gustav Cohen, were elected to the regional committee of the federation.

Most of Opava’s Jews worked in commerce. Some exported liquors, while others worked as artisans and professionals.

In 1921 Opava’s Jewish population was 1,127. In 1930, 971 Jews (2.6% of the population) lived in Opava.

Notable figures born in Opava include the artist Lev Haas and the film director Kurt Goldberger.

THE HOLOCAUST

As a result of the Munich Agreement of September 1938, a year before the outbreak of World War II (1939-1945), the Czechoslovak Republic was dismembered and the Sudeten region, including Opava, was ceded to Nazi Germany. The Jews living in the region escaped to other areas that were not part of Nazi Germany.

The Germans set fire to Opava’s synagogue in November 1938.

In March 1939 the German army entered the Czech territory of Bohemia and Moravia, and the region became a protectorate of the Third Reich. The Jews of Opava shared the same fate as Jews throughout the protectorate. Opava’s Jews were deported to the ghetto of Terezin (Theresienstadt), and from there to concentration and extermination camps, mainly in Poland. About a thousand Jews were deported from Opava to Terezin on September 11, 1942.

The synagogue was destroyed in an air attack in 1945, and one cemetery was destroyed by the Germans.

POSTWAR

At the end of the war a few survivors from Opava returned. Together with some new Jewish settlers from Carpatho-Russia, they revived the city’s Jewish community. In 1948, 82 Jews resided in Opava, 66 of them registered in the community. That year the new cemetery, which had sustained heavy damage during the war, was renovated.

In 1959 the community of Opava became affiliated with the Jewish community of Ostrava. In 1970 there was still an active community in Opava. By the end of the century, however, community life had come to an end.