The Jewish Community of Lublin

Lublin

A city in Poland

Lublin is one of the largest cities in Poland, and is the capital and center of the Lublin Voivodeship.

In the 16th and 17th centuries Lublin was famous for its fairs. Annexed by Austria in 1795, it was incorporated in Russian Poland in 1815. From 1918 to 1939 it was in Poland, and during World War II (1939-1945) it was under German occupation. After the war, Lublin was again part of Poland.

21ST CENTURY

The building and grounds of the Chachmei Lublin Yeshiva were given to the Jewish Community of Warsaw in 2002-2003. The Jewish Community renovated the building, which had fallen into disrepair, and, based on prewar photographs, restored many of the building’s religious features. The Lublin Branch of the Jewish Community of Warsaw began using part of the building for community activities in 2006. The building’s official reopening took place in February of 2007, with over 600 in attendance.

In May 2005 the Jewish world celebrated the Siyyum HaShas, marking the end of the 7-year cycle of reading a page of Talmud daily. One of the celebrations took place at the Chachmei Lublin Yeshiva, to honor its former head, Rabbi Meir Shapiro, who invented the system in 1924. A memorial service was also held for Rabbi Shapiro in 2008 in the Chachmei Lublin Yeshiva, to mark the 75th anniversary of his death. A new Ark and chandelier were installed in the synagogue to honor the occasion.

The old Jewish cemetery site is located in the Kalinowszczyna district. Most of the tombstones were destroyed during World War II, but some of have survived. The new Jewish cemetery was almost completely destroyed during the war. Remnants of the cemetery include the southeastern section of the wall, and the ohel built over Rabbi Meir Shapiro’s grave.

HISTORY

Jews were first mentioned as transients in Lublin in 1316. By the 15th century a community had developed, and became a place of refuge for a number of Jews who had been expelled from other areas. During the second half of the 16th century land was granted to the community so that it could establish a cemetery, and build institutions. Shalom Shachna established a yeshiva in the city in 1518; he was later appointed as the Chief Rabbi of Lublin in 1532. Economically, Jews were allowed to set up movable stalls for shops but not to erect buildings. There was also a Hebrew printing press that began publishing Hebrew books and prayer books in 1547.

In 1602 there were 2,000 Jews in Lublin.

When the Polish high court convened in Lublin between the 16th and 18th centuries, tensions between the city’s Jewish and non-Jewish residents rose significantly, particularly when the court was trying a blood libel case (the first blood libel trial in Lublin took place in 1598). The hearings were followed by attacks on the Jews; some were murdered and their property stolen. If the high court sentenced the accused to death, the execution usually took place on a Saturday in front of the Maharshal Shul (synagogue), and elders of the kehillah and other Jews had to attend. An execution was often followed by an attack on the Jewish Quarter. Additionally, like Jews throughout Poland-Lithuania, the Jews of Lublin suffered greatly during the Chmielnicki uprisings in 1648-1649. Yet another period of hardship followed in the second half of the 18th century with the disintegration of the Polish state.

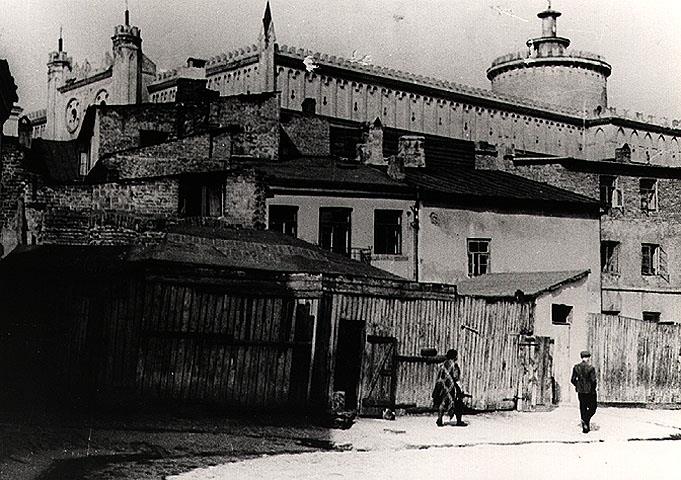

However, in spite of these hardships, Lublin became both a cultural, economic, and religious center for Polish Jews, due mainly to the fairs and yeshiva. The Council of Four Lands, the central Jewish body of authority, often met in Lublin between 1580 and 1725. Community institutions included a well-organized chevra kaddisha and a "preacher's house," which provided visiting preachers with food and lodging. The fortified Maharshal Shul, the most famous synagogue in Lublin, was built in 1567. It burned down in 1655, but was later rebuilt.

Chasidism played a prominent role in Lublin, mainly through the influence of the local Tsaddikim, including Jacob Isaac Ha-Chozeh ("The Seer") of Lublin, and, from the mid-19th century, the Eiger dynasty. At the same time, there were also some community rabbis who were strongly opposed to the Chasidic movement, particularly Azriel Horovitz (late 18th century) and Joshua Heshel Ashkenazi.

A cholera epidemic broke out in 1829, resulting in the deaths of many Jews. As a result of the increase in burials, a new Jewish cemetery was established that year.

Educational institutions for the community’s children included a cheder and the yeshiva. Beginning in the second half of the 19th century, the first Jewish schools were founded where the language of instruction was Russian or Polish. The city’s first private Jewish high school was opened in 1897.

During the early 20th century the Jews of Lublin were politically and culturally active. The Jewish Public Library opened in 1917. The Polish-Jewish magazine, “Myśl Żydowska” (“Jewish Thought”), began publication in 1916, and the Yiddish “Lubliner Tugblat” (“Lublin Daily”) began publication in 1918. The Bund was also active during this period.

Construction on the famous yeshiva, Chachmei Lublin, began in 1924; the cornerstone laying event was attended by a crowd of about 20,000. The yeshiva opened in 1930, led by Rabbi Meir Shapiro, the Chief Rabbi of Lublin. Rabbi Shapiro was a particularly well-known rabbi, in part by pioneering the Daf Yomi system of Talmud study in 1924.

In 1939 there were over 42,000 Jews living in Lublin.

THE HOLOCAUST

Lublin was captured by the Germans on September 18, 1939. During the very first days of the occupation Jews were forcibly evicted from their apartments, physically assaulted, and conscripted for forced labor. Some Jews were taken as hostages, and all of the men were ordered to report to Lipowa Square, where they were beaten. For a while, the Nazis entertained the idea of turning the Lublin District into an area where Jews from the German-occupied parts of Poland and various other areas incorporated into the Reich could be concentrated.

The existing Jewish community council remained in office until January 25, 1940, when the Judenrat was appointed. During the first period of its existence, the Judenrat did not only execute Nazi orders, but initiated a number of projects designed to alleviate the harsh conditions. Public kitchens were established in order to provide meals for refugees and the local poor. The ghetto was divided into a number of units for the purpose of sanitary supervision, with each unit run by a doctor and several medical assistants. Additionally, there were two hospitals with a total of over 500 beds, and a quarantine area in the Maharshal Shul with 300 beds. Hostels were established to house abandoned children, but the Judenrat did not succeed in reestablishing the Jewish school system, and the schooling that was available to children was carried on as an underground operation.

At the beginning of 1941 the Jewish population of Lublin was about 45,000, including approximately 6,300 refugees who had fled from other areas. In March of that year, the Nazis ordered a partial evacuation of the Jews in preparation for the official establishment of the ghetto. Between March 10 and April 30, 1941 about 10,000 Jews were driven from Lublin to villages and towns in the area. The ghetto was created at the end of March, and eventually held a population of about 34,000. On April 24, 1941, the ghetto was sealed, and Jews were no longer permitted to leave.

With the commencement of Operation Reinhard, the secret Nazi plan to kill the majority of Polish Jewry, the Jews of Lublin were among its first victims. The liquidation of the ghetto began on March 16, during which time 30,000 Jews were dispatched to the Belzec death camp. The rate of deportation was fixed at 1,500 per day, and attempts by the Jews to hide were of no avail.

The remaining 4,000 Jews were taken to the Majdan Tatarski ghetto, where they lived for a few more months under unbearable conditions. On September 2, 1942 an aktion resulted in the murder of 2,000 Jews; another 1,800 were killed at the end of October. Approximately 200 survivors were sent to the Majdanek concentration camp.

Lublin was also the site of a prisoner-of-war camp for Jews who served in the Polish Army. The first prisoners arrived in February 1940. Those who came from the area of the general government were set free, but about 3,000, whose homes were in the Soviet-occupied area or in the districts incorporated into the Reich, remained in detention. The Judenrat tried to extend help to the prisoners, and there was also a public committee that provided the inmates with forged documents in order to enable them to leave the camp.

When the Germans stepped up the extermination campaign, there were some attempts to escape from the camp; the Germans responded to this attempt by imposing collective punishments on the prisoners. Nevertheless, there were continued efforts to obtain arms for resistance, and some prisoners succeeded in escaping to the nearby forests, where they joined the partisans; indeed, some of the escaped prisoners assumed senior command posts in the partisan units. The last group of prisoners was deported to Majdanek on November 3, 1943

The Red Army liberated Lublin on July 24, 1944. The next day, Polish army and guerilla units entered the city. A few thousand Jewish soldiers served in those units, and among the guerillas was a Jewish partisan company under Captain Jechiel Grynszpan.

POSTWAR

Until the liberation of Warsaw in January 1945, Lublin served as the temporary Polish capital. Several thousand Jews, most of whom survived the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, settled in Lublin. However, the majority of them left between 1946 and 1950, due to Polish antisemitism. The Jewish Cultural Society was functioning in Lublin until 1968, when many of the remaining Lublin Jews left Poland.

A monument dedicated to the Lublin Jews who were killed during the Holocaust was dedicated in 1963. Later, in 1985 a memorial plaque was placed on the wall of the building that once housed the Chachmei Lublin Yeshiva.

Henryk Wieniawski

(Personality)Henryk Wieniawski (1835-1880) Violinist and composer. Born in Lublin, Poland. He began to study at the Paris Conservatory when he was eight. His debut was in 1848. In 1860 he was nominated the Czar’s solo violinist. From 1860-1872 he taught at the St. Petersburg Conservatory and greatly influenced the Russian violin school. In 1872 he toured the United States with Anton Rubinstein and Europe with his pianist brother Josef. He was a virtuoso, perhaps the greatest violinist of the generation after Paganini.

His compositions reflect his ability as a violinist and combine it with a mature romanticism. He composed many works for the violin and his two violin concertos (1853 and 1870) are often performed. He is the nephew of pianist Edouard Wolff and his youngest daughter Irene, later Lady Dean Paul, composed under the pen name Poldowski. He died in Moscow, Russia.

Josef Wieniawski

(Personality)Josef Wieniawski (1837-1912), pianist and composer, born in Lublin, Poland (then part of the Russian Empire). He gave concerts all over Europe from 1850-1855 with his brother Henryk. He studied in Paris and later, in 1855/56, with Franz Liszt in Weimar, Germany. From 1865-1869 he taught at the Moscow Conservatory and later directed his own music school there. In 1876 Wieniawski moved to Brussels where he became a professor at the conservatory.

He composed works for orchestra (including a piano concerto), chamber music and numerous piano pieces (waltzes, mazurkas and etudes). He died in Brussels, Belgium.

Henrik Erlich

(Personality)Henrik Erlich (1882-1941), journalist, Jewish socialist leader in Poland, born in Lublin, Poland (then part of the Russian Empire) to a wealthy Orthodox Jewish family. His father was a Hassid who acquired some secular education and later joined Hovevei Zion movement. Erlich received a full secular legal education. He studied law in Warsaw, where he encountered Socialist movement for the first time and joined the Bund. He was arrested on several occasions for revolutionary activity and was finally expelled from the university. He therefore continued his studies in St Petersburg, Russia. From 1913 he belonged to the Central Committee of Bund. During the Russian Revolution of 1917 he was a member of Petrograd Soviet executive committee and member of Soviet's delegation to England, France and Italy. After the revolution in Russia, he moved back to Warsaw. In Warsaw he met Wiktor Alter, one of the most influential leaders of Bund. As a member of Bund, he became a member of the Warsaw municipality after Poland had regained its independence in 1921. Erlich took an active part in socialist propaganda activities and edited a number of periodicals including "Glos Bundu" (“Voice of Bund”) (1901-1905) and “Volks Zeitung” (“People’s Newspaper”). In 1925 he was elected to the Warsaw kehilla council as one of 5 Bundists out of 50 members. Bund joined the Comintern in 1930 and Erlich found himself on its executive body.

After the outbreak of World War 2, Erlich made his way to the part of Poland that had come under Soviet control. He was almost immediately arrested by Russian authorities and sentenced to death. However, the sentence was commuted to 10 years imprisonment. Erlich was eventually released as a result of of the Sikorski–Mayski Agreement between the Soviet Union and Poland in 1941. At about the same time Erlich was supposed to join Gen. Sikorski (the Prime Minister of the Polish Government in Exile) in traveling to London where it was intended that Sikorski should join the Polish government. However, in December, Erlich, together with Victor Alter were once again arrested by the NKVD in Kuybyshev. No reason was given for their arrest. According to various sources at the time, he was charged with spying for “enemies of the Soviet Union”. The Soviet authorities later announced that he had been executed, but it was widely believed that Henryk Erlich committed suicide in the Soviet prison in Kuybyshev.

In 1991, Victor Erlich, Henryk Erlich's grandson was informed that according to a decree passed under Russian president Boris Yeltsin, Erlich had been "rehabilitated" and the repressions against them had been declared unlawful. While the exact place where he was buried is unknown, a cenotaph was erected at the Jewish cemetery on Okopowa Street in Warsaw in 1988. The inscription reads "Leaders of the Bund, Henryk Erlich, b. 1882, and Wiktor Alter, b. 1890. Executed in the Soviet Union".

Jacob Glatstein

(Personality)Jacob Glatstein (1896-1971) Poet and novelist. Born in Lublin, Poland, Glatstein emigrated to the United States in 1914. and co-founded the In-Zikh Yiddish poetry movement in 1920. His poetry collections include Yankev Glatshteyn (1921), Fraye Ferzn (1926), Kredos (1929), Yidishtaytshn (1937), Gedenklider (1943), Shtralendike Yidn (1946), Dem Tatns Shotn (1953), Fun Mayn Gantser Mi (1965), Die Freyd fun Yidishn Vort (1961) and A Yid fun Lublin (1966). Glatstein is also the author of many novels and essays, most of which were written for the New York Yiddish daily “The Day” and various Yiddish periodicals. He died in New York, USA.

Yoel Sirkes

(Personality)Yoel Sirkes (1561-1640), rabbi, Talmudic scholar and legal commentator, born in Lublin, Poland. He served as rabbi of several communities including Pruszany, Lubkow, Lublin, Miedzibozh, Belz, Szydłówka and finally Brest-Litovsk and Krakow (from 1519) where he was head of the beit din and of the yeshivah. He was one of the outstanding rabbinical authorities in Poland, writing glosses on the Talmud, hundreds of responsa and especially Bayit Hadash, a commentary on Yaakov ben Asher’s classic code Arbaah Turim analyzing its Talmudic sources and its subsequent legal interpretations. It is printed in standard editions of Yaakov ben Asher’s work. His responsa constitute an important source of all aspects of Jewish life in Poland and Lithuania in his time. His son-in-law and pupil was another great commentator on the codes, David ben Shemuel Ha-Levi.

Symcha Trachter

(Personality)Symcha Trachter (1893-1942), artist born in Lublin, Poland (then part of the Russian Empire). In 1911 he settled in Warsaw, Poland. He studied painting in Academy of Fine Arts there between 1916 and 1920 and then continued his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts of Krakow in workshops of Jacek Malczewski, Teodor Axentowicz and Stanisław Dębicki.

Tracter went to Vienna, Austria, where he studied for six months and then in 1927 he moved to Paris, France, where he was inspired by Ecole de Paris movement. Upon his return to Poland he settled in Lublin. He visited Kazimierz Dolny very often.

During the Nazi occupation of Poland in WW2, he was in Warsaw Ghetto. Together with Feliks Frydman he made frescos in the board room of the Judenrat in Warsaw. He supported himself by working in a cooperative manufacturing whetstone for sharpening knives and scouring powder. During night of 26 August 1942, along with other members of the cooperative, he was deported to the Nazi death camp at Treblinka and murdered there.

Hayyim Judah Ben Kalonymus Ehrenreich

(Personality)Hayyim Judah Ben Kalonymus Ehrenreich (1887-1942), rabbi. Ehrenreich was a rabbi in Holesov, Moravia (now in the Czech Republic); Deva, Transylvania (now in Romania); and Humenne, Slovakia (then part of Czechoslovakia). In this last community, to which he was appointed in 1930, he devoted himself to a study of Talmudic literature. In 1920 he published an important pamphlet Israel bein ha-Amim ("Israel Among the Nations") dealing with Jewish survival. Other works included Saadiah Gaon's "Shelosh Esreh Middot" (1922); Abraham Klausner's "Minhagim" (1929); and "Givat ha-Moreh" (1936). From 1920 Ehrenreich published parts of Seder Rav Amram Ga'on with his own commentary and edited a monthly journal, "Ozar ha-Hayyim", from 1924 to 1938.

Rabbi Ehrenreich and his family were killed by the Nazis in Lublin, Poland, in 1942.

Der Ofen von Lublin from In Memoriam, Song cycle for voice and piano

(Music)Der Ofen von Lublin ("The Oven Of Lublin" - in German)

Original recording from Sounds of Memory. Produced by Beit HaTfutsot in 1995

This poem was written by Theodor Kramer during WWII. The piece by Norbert Glanzberg premiered at Beit HaTfutsot on the evening after Holocaust Remembrance Day, 1994.