"El Transito" Synagogue in Toledo, Spain

Haim F. Ghiuzeli

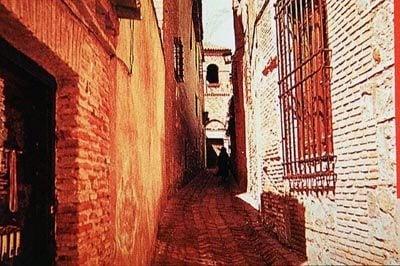

The El Transito Synagogue in Toledo, Spain, was built by Samuel (Shmuel) Ben Meir Ha-Levi Abulafia (also spelled Al-Levi and Allavi) (c.1320-1360). Scion of an old Jewish family, Samuel Ha-Levi Abulafia was advisor and treasurer (tesorero real) to King Pedro I of Castile (1350-1369) (also known as Pedro the Cruel) from 1350. Samuel Ha-Levi Abulafia is remembered as the founder of a number of synagogues in the Kingdom of Castile, but the one constructed on the grounds of his palace in Toledo was by far the grandest. The entire complex was located inside the medieval Jewish quarter, juderia, at a central location within the walls of the city of Toledo. The synagogue was intended to serve as a private house of worship for Samuel Ha-Levi, who was a prominent member of the Jewish community of Toledo, and was connected to his house by a private gate. The synagogue was built to the plans of the master mason Don Meir (Mayr) Abdeil and was dedicated in 1357. The original name of the synagogue is not known; some modern authors tend to call it after the name of its founder instead of El Transito, the name given by the Christians and by which name the building has been known for the last three hundred years.

Samuel Ha-Levi Abulafia’s fate took a turn for the worse in 1360, when King Pedro arrested and imprisoned him in Seville, having accused Samuel of taking part in a conspiracy against him. Whilst in prison Samuel was tortured to death and all his possessions were confiscated by the king including his house and the synagogue. The synagogue was spared when the Jewish district of Toledo was attacked by the mob in 1391, during a wave of anti-Jewish massacres. When the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, “the great synagogue that the Jews used to have in Toledo” was granted by the king and queen of Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella, to the religious order of Calatrava. Two years later the complex was turned into the San Benito priory with the former women’s section and the study rooms serving as hospice for the knights of the order while the main prayer hall was converted into a church known as the Iglesia de San Benito. During the 16th century some minor alterations were made in order to fit the needs of Christian worship and a bell tower was built on to the exterior. From the 17th century the San Benito church was known as Ermita del Transito, shortened popularly from El Transito de Nuestra Senora (“Our Lady’s Transit”), the title of a well- liked painting by Correa, now in the collection of the Prado Museum in Madrid, which used to decorate the altar. During the 18th century the complex housed a monastery, then during the Napoleonic wars in the early 19th century it was converted into a barracks, and then reverted to being a monastery for most of the 19th century. In 1877 the former synagogue was declared a National Monument. The structure underwent a series of restorations until 1910, when it passed into the care of the Museo del Greco in Toledo, of the Vega-Iclan foundation, and it remained in its custodianship until 1968. During the 20th century the building of the synagogue and the adjacent buildings underwent a number of restorations. During the thorough renovation of the 1960’s, the building received new furnishings, including tapestries donated by the Pinto-Coriat family.

In 1970 the synagogue, along with the neighboring Sephardi Museum (Museo Sefaradi), established in 1964, became the National Museum of Judeo-Spanish Art, a state institution under the control of the Spanish Ministry of Education and Culture.

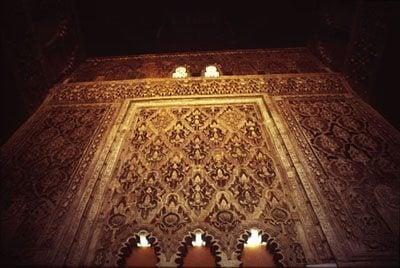

The El Transito Synagogue has a rectangular prayer hall of about twenty-three metres by twelve metres and a high of nine and a half metres. The exterior walls, which are of mixed stone and brick typical of Muslim architecture in Spain, are quite plain, with an aljima type of window (consisting of a pair of horseshoe arches) above the entrance door. In contrast, the interior displays one of the most splendid examples of mudejar architecture in Spain. The design of the synagogue recalls the Nasrid style of architecture that was employed during the same period in the decorations of the Alhambra palace in Granada as well as the Mesquita of Cordoba, and parts of the Alcazar palace in Seville that were constructed at the same time at the initiative of King Pedro.

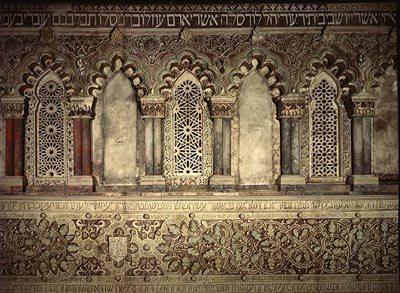

A two-storey women’s section was located in a separate room adjacent to the northern wall of the synagogue. The eastern wall still has three niches that used to shelter the Holy Ark (heikhal) with the Torah scrolls. During excavations conducted in 1987 by Spanish archaeologists, remains of what appears to have been a trapezoidal room with blue tiled floor were unearthed at the exterior of the eastern wall. The assumption is that the room served as a separate heikhal. No indication has been preserved of the location of the bimah inside the prayer hall. The interior walls of the prayer hall are decorated with colorful geometric and floral motifs in plaster characteristic of the mudejar art of the age. It is possible that their pattern might have been inspired by the lavish textiles imported from the Muslim ruled regions of southern Spain. The most elaborate decoration was reserved for the eastern wall. Its upper section features an arcade of septfoil arches, and the central section is covered with arabesque patterns. The artesonado ceiling is made of cedar wood and is divided into six sections by large pairs of beams. Tradition has it that the wood was brought by Samuel Ha-Levi from Lebanon in imitation of King Salomon. The original floor was covered by mosaics, of which only fragments have survived. Light enters from a number of windows in the upper section of the walls.

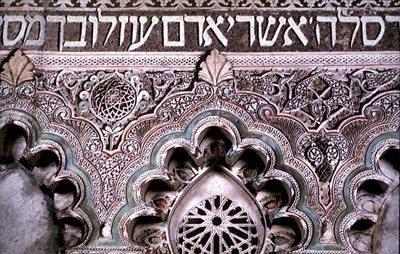

Perhaps the most impressive elements of the interior decoration are the numerous monumental Hebrew and Arabic inscriptions that adorn the walls, the arches around the windows and some column capitals. The Hebrew inscriptions of the El Transito Synagogue are undoubtedly the most remarkable example of medieval Jewish monumental epigraphy. Most texts are taken from the Bible, especially from the Book of Psalms, Chronicles, and Habbakuk, while others glorify King Pedro I, Samuel HaLevi Abulafia, the patron and builder of the synagogue, and Meir Abdeil, its architect. The frieze of the upper section of eastern wall above the windows boasts the Hebrew inscription: “Behold the Sanctuary that is consecrated in Israel and the House that Samuel built”1. The inscriptions in Arabic bear witness to the high status enjoyed by the Arabic culture among the Jews of Spain, even amongst those living under Christian rule. The coat of arms of the Kingdom of Castile is repeated a number of times on the walls of the synagogue as a proof to the loyalty of the local Jews to the King.

The style of the El Transito synagogue as well as other surviving Jewish medieval monuments in Spain served as source of inspiration for numerous synagogues that were built in Europe during the 19th century. The richness of the decoration was considered by the post-emancipation Jews of Europe as a proof of the high social status that the Jews of Spain enjoyed prior to their expulsion.

A replica of part of the upper section of the eastern wall of the El Transito Synagogue is displayed in the Synagogues Hall at ANU – Museum of the Jewish People.

Notes

1. English translation by Esther W. Goodman (1992:61)

Address

Sinagoga del Transito

Paseo Samuel Levi s/n

Toledo 45002

Spain

Phone: 34-925-22 3665

Fax: 34-925-21 5831

Bibliography

GOODMAN, Esther W. Samuel Halevi Abulafia’s synagogue (El Transito) in Toledo. Jewish Art, 18(1992):58-69

PALOMERO PLAZA, Santiago. Excavations around the Samuel Halevi synagogue (Del Transito) in Toledo. Jewish Art, 18(1992):48-57

RALLO GRUSS, Maria Carmen. Restauración de las yeserias de la Sala de Mujeres de la sinagoga de El Transito (Toledo). Sefarad, 49:2(1989):397-406