The Jewish Community of Sofia

Sofia

In Bulgarian: София / Sofija

Capital of Bulgaria; located in central-western part of the country

In the second century B.C., the emperor Traianus granted to the city the name Serdica Ulpia. Later, the city was also called Sredets. In the 14th century the city's name was changed to Sofia, for the large church, Sainte Sofia. The Ottoman conquerors (1392) converted the church to a mosque, but the name remained. The city was a principal landmark and crossroad between East and West, through which convoys of goods passed on the route from Europe to the capital of the Ottoman Empire, Istanbul. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Sofia's importance declined and in 1879, before the end of the war between the Ottoman Empire and Russia, Sofia was declared the capital of free Bulgaria. Beginning in the 1880s, the city expanded, annexing neighboring villages. Sofia's population increased from 20,500 in 1880 to 435,000 in 1946; in 1992 the city's population was 1,108,000.

Jewish Community

Hebrew and Ottoman sources and documentation of Sofia's Jewish population exist as far back as the 14th century. Jews may have lived in Sofia before that period, but documentation thereof does not exist.

During the Ottoman period Sofia and the surrounding villages constituted an agricultural and commercial center. The Jews lived among a mixed population of religions and nationalities: Valachs, Moldavians, traders from Ragusa (now Dubrovnik), Muslims and Russian Orthodox Christians. Comprehensive documentation does not exist regarding the origin of the Jewish community. Relevant literature notes that concurrently with the Ottoman occupation, Sofia had two Jewish communities: a Romaniote (Jews from Byzantium who, in Jewish sources they are also called "gargus" or Greeks, since they spoke the Greek language) and the other community was made up of refugees expulsed from Hungary in 1360. Each community had its own synagogue. In the year 1470 a small number of Jews who were expulsed from Bavaria arrived in Sofia and an Ashkenazi synagogue was established in the city.

Spanish exiles arrived in Sofia at the beginning of the 16th century. These residents were very dominant and gradually overrode the place of the Romaniote and the Ashkenazi Jewish communities. The first Sephardic Jews in Sofia came from Thessaloniki. As from the 16th century, information and data regarding the daily life of Sofia's Jewish community expanded and increased.

Jews in Sofia as from the middle of the 16th century were engaged in textiles, production and trade in cheese and granting interest-bearing loans.

In the years 1560–1570 Sofia numbered approximately 650 Jews. According to documents from the 17th century regarding collection of taxes from Sofia Jews, Sofia's Jewish population comprised then 2,600 individuals aged 18 or more. Sofia became the home of the largest Jewish population in Bulgaria; previously, the principal Jewish populations resided in Nicopole, Vidin and Plovdiv.

The daily life of Sofia's Jews is reflected in three letters dating from the 1630s, written in Yiddish and in Hebrew, sent by Ashkenazi Jews to Austria and to Italy. The writers found shelter in Sofia and recommended to their relatives to join them and to benefit from the city's life and environment. The letters also note the difficulties of trade with Austria and the lack of security on the roads, because of the war. One trader, David Cohen Ashkenazi, decided, therefore, to try his luck in trade with Poland. His letter also tells of an epidemic that caused deaths in Thessaloniki and in Edirne (Adrianople), but did not reach Sofia and Pleven. These letters also told of the work of Sofia's Jewish women, including silk trade, midwife and interest-bearing loans. A letter from 1532, regarding family life, explains the comfortable life of Sofia's Jews. This population found subsistence also outside the city, acquiring from the authorities leasehold rights for taxation, e.g. Yitzhak Ben-Arslan (possibly Aryeh) and Abraham Ben-Yitzhak, Sofia residents, acquired rights to collect import taxes (Mukata) for Sofia and for the port of Nicopole, for the 1561 – 1562 tax year.

Jews maintained relationships with local residents, based on their commerce with the city's Muslim and Christian population. The sale agreement for a house, dated 1680, reflects the status of the Jewish buyer and the mixed residence of Jews, Muslims and Christians in a middle-class neighborhood of the city, notwithstanding the government's aspiration to separate ethnic groups through legislation and orders. In the year 1680, the Kadiasker of Rumelia demanded from the Kadiasker of Sofia that Muslim women cease to use the public bath together with Jewish women and "other non-believers", since this is a clear breach of Islamic law.

Disputes between Jews were generally settled in Sofia's rabbinic court. Jews occasionally transmitted requests for settlement to Muslim authorities, to the dissatisfaction of the rabbis, who regarded decisions handed down by non-Jews as serious infraction of Jewish law. Most of those requesting settlement were Jewish traders, especially the wealthy segment, who were dissatisfied with the decisions issued by the rabbinic courts. The Muslim courts generally considered Jews fairly. In one case, apparently extraordinarily, which was initiated in the town of Samokov and was transferred to a Sofia court, the Muslim authorities disclosed a hostile and strict position: The son of Jafar Ibn-Abdallah, a respected resident of Samokov, killed a young Jew, Israel Ben-Levy. Samokov's Qadi convinced the dead youth's family to accept monetary compensation, in order to prevent tension between Jews and Muslims. However, the respected father requested to return the amount to him, arguing that Israel Ben-Levy converted to Islam and then reneged, and that his son wished to repay the compensation in return, and when he refused, killed him. The Jewish family was forced to leave Sofia. The Sofia court accepted the petitioner's claims and required to Jewish parents to return the compensation.

The Jews paid regular taxes levied on non-Muslims and, additionally, were subject to special taxes. The Jews of Sofia were also subject to pay expenses in respect of the visit of Vizier Hussein Assa from Belgrad to Monastir. Taxes levied on Jews were calculated separately.

Sofia constituted an important commercial center. Documentation reflects a Jewish trader from Sofia who maintained commercial relations with a partner in Venice. Additional evidence of commerce between Sofia and Venice is found in an exchange note dated 1649, written in Ladino and Hebrew, between Jewish traders from the two cities. The invoice was sent by a third partner, in Paris. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Jews participated actively in commerce between Sofia and Ragusa (now Dubrovnik) on the Adriatic Sea. A note dated 1641, sent by Ragusa authorities to the Ottoman authorities, requested reduction of taxes levied on their subjects in Sofia, and protection of their citizens from "the disturbances and ignorance by the Jewish traders in the city". In 1619, the Ottoman authorities issued an order also enabling Catholics to trade in wool. The Jews opposed the order since they were committed to provide the requirements for their colleagues in Thessaloniki, engaged in the wool clothes industry for the Janissaries (Ottoman soldiers).

Notwithstanding the importance of foreign trade, most of Sofia's traders found subsistence within the empire's borders, transporting their goods in caravans. A document exists regarding a Jewish trader who was killed on route from Thessaloniki with a shipment of textiles to Sofia. In another caravan, between Sofia and Skopje, Macedonia, a Belgrade Jew was killed. The caravans were mixed and included Muslims, Christians and Jews. In an attack on a caravan en route from Sofia to Thessaloniki in 1606, for example, both Jewish traders and the Qadi of Sofia and his wives, were killed.

18th and 19th Centuries

In the middle of the 18th century, Sofia's Jewish community was the largest in Bulgaria. In the same years, the chief rabbis were Reuven Ben-Yakov Tibia (chief rabbi in years 1752 – 1795), Yitzhak Zadka, Yakov Shmuel Madjar, Yosef Yekutiel, Vidal Fasi, Haim Yosef Elyakim and others. Some published important compositions distributed also outside of Bulgaria. In 1808, Rabbi Rachamim Abraham Venture arrived Sofia from Spaletto (now Split, in Croatia) and held the position of chief rabbi until 1820.

In 1876, Rabbi Gabriel Almoslino, born in Nicopole, arrived in Sofia. Concurrently with the end of the war between the Ottoman Empire and Russia, and the establishment of independent Bulgaria in 1878, Almoslino became the chief rabbi of Bulgarian Jewry. He represented the Jewish minority at the first convened meeting of independent Bulgaria, held in the historical capital of Tarnovo.

During the war between the Ottoman Empire and Russia (1877 – 1878), with battles on the outskirts of Sofia, concern existed that the retreating Ottoman army would burn the city. The Jewish population was the subject of numerous stories of courage and heroism to defend Sofia and to extinguish fires. However, Jews in Sofia, and in other locations, were objects of theft and plundering by the Russian army and by Bulgarian civilians.

According to a census from 1880, Sofia's Jewish population numbered 5,000, with six synagogues. Until 1897 the cemetery was located in the silk market, but the area was requisitioned by the municipality, notwithstanding the community's opposition. Since that year, the cemetery is located in a separate section next to the general cemetery. Some twenty old tombstones were transferred to the new cemetery location from the previous silk market location.

Toward the end of the 19th century, a central institution and council of Bulgarian Jewry, the Consistory, was established.

20th And Early 21st Centuries

On September 23, 1909 Sofia's New Synagogue was consecrated. The event, among the most important in the history of Sofia's and Bulgaria's Jewry, was very joyous and the guests included the Royal Family of Bulgaria, ministers and honored guests. The synagogue was magnificent and large, with 1,300 seats.

Important rabbis in the period included Dr. Ehrenpreis, Abraham Pipano, author of "Hagor Ha'apod" ("The Belted Sweater"), and Dr. Asher Hananel, the last rabbi of Bulgarian Jewry, who passed away at the end of the 1940s.

In the period of the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), Sofia's Jewish population numbered 17,000, out of a total population of 82,621. Of the Jews, 1,421 served in the Bulgarian arm. The UAI, a social organization, mobilized contributions to assist families of Jewish soldiers.

The community's public institutions included "Beit Ha'am" ("The People's House") (established in 1934), and a Jewish hospital, banks managed by Jews, charities and a school for all age groups. In the mid-1930s, approximately half of Bulgaria's Jews lived in Sofia, where all principal institutions of Bulgarian Jewry operated. In the same period, an attempt was made to establish a Jewish theater, whose actors were later integrated in the capital's theaters. A symphony orchestra was also established, most of whose participants were Jews. The well known "Tzadikov" choir was established in 1908 and became famous after World War I. The choir contributed greatly to cultivation of culture among Jews in Sofia and in Bulgaria as a whole, and continued its activity also in Israel.

Zionist activity among Sofia's Jews included parties and youth movements including "Hashomer Hatzair" ("Young Scouts"), "Beitar", "Hanoar Hatziony" ("Zionist Youth"), "Maccabi" and others. Sofia's Jewish community published newspapers, in Ladino and in Bulgarian, which reflected a range of positions and opinions of various sectors – Zionist and others.

Holocaust

At the outbreak of World War II, in September 1939, Sofia's commercial neighborhoods were the stage of disturbances and outbreaks, and Jewish stores were damaged. The neighborhoods' 4,000 foreign citizens were deported from Bulgaria; the Consistory's involvement did not help.

In February 1940, following the trend of Bulgaria's approach to Nazi Germany, King Boris of Bulgaria appointed as Prime Minister Professor Bogdan Pilov, a pro-German. With Germany's influence, in October 1940 Bulgaria enacted the National Protection Law, which restricted rights of Jews. The regulations according to the Law, which took effect in February 1941, cancelled all rights to which Jews were previously entitled. Jews were required to wear a Jewish badge, their homes and businesses were marked, and they were expelled from institutions of higher education.

In March 1941, Bulgaria joined the Axis and the German army entered Bulgaria. Jewish men were mobilized in work units, given hard, oppressive work tasks and were retained in difficult conditions in central forced labor camps. However, the German plan for deportation of Bulgarian Jewry to death camps did not succeed, thanks to the firm resolve of many entities among the Bulgarian people.

At the government's demand, a detailed list was prepared in Sofia at the beginning of 1943 of "wealthy, respected and positioned Jewish families". In May 1943, a decision was reached to deport the capital's Jews to remote towns, as a preparatory stage in deportation of Bulgaria's Jews eastward. When these plans became known, a demonstration ensued, most of whose participants were Jews. The demonstration was diffused within minutes and many were detained. Among the detainees were Zionist leaders and Consistory members. Bulgarian public figures, church officials, and Jewish leaders, including Sofia's Rabbi Daniel Tsion, were involved in feverish efforts to cancel the plan. The detainees were transferred to a death camp near Somovit.

On May 26, 1943, deportation of 25,743 Sofia Jews commenced, and ended after two weeks. The Jews were permitted to take their belongings and property and were sent to twenty remote towns. Only several dozen families, with special approval, remained in the capital; these included families of converts and individuals whose presence was required for economic reasons.

In the remote towns, the authorities required that the deportees be housed in Jewish residences only. Food was minimal, freedom of movement in public places was restricted and radios and vehicles were foreclosed. However, most Bulgarians remained faithful to human rights and helped the Jews in this difficult time. In December 1943, the deportees were permitted to return to Sofia for short periods in order to arrange their private business matters.

Bulgaria was liberated from the Nazi occupation on September 9, 1944.

In May 1949, after the large scale immigration from Bulgaria to Israel (1948–1950), approximately 5,000 Jews remained in Sofia.

During the years 1989–2002, more than 3,000 Bulgarian Jews immigrated to Israel, most of them from Sofia.

In the 1990s, community life centered on "Beit Ha'am", various social activities and clubs were conducted and a Sunday school for young children functioned. Holidays were noted mainly in the renovated synagogue or in "Beit Ha'am". In 1992, activity of "Hashomer Hatzair" was renewed in Sofia, and during the 1990s seventy of its members immigrated to Israel. The "Bnei Brit" youth movement was also active; most of the activity was financed by the "Joint".

At the beginning of the 21st century, approximately 3,000 Jews remained in Sofia, including many who have intermarried.

.

Rafael Arie

(Personality)Rafael Arie (1922-1989), bass singer, born in Sofia, Bulgaria. He first played the violin but soon began to study singing with Brambaroff, the leading baritone of the Sofia Opera. During World War II he was sent to forced labour camps. After the war Arie joined the Sofia Opera company and in 1946 he won first prize at an international competition held in Geneva. In 1947 he sang leading bass roles at La Scala in Milan. In 1948 Arie joined his family and settled in Israel. In 1951 he was chosen by Stravinsky to sing the role of Trulove at the first performance of the composer’s opera THE RAKE’S PROGRESS. He soon established his fame as a leading bass in major opera houses around the world. Arie was head of the opera department at the Tel Aviv Rubin Academy. He died in Switzerland.

Alexis Weissenberg

(Personality)Alexis Weissenberg (1929– 2012) pianist, born in Sofia, Bulgaria, whose mother started to teach him to play the piano. His second piano teacher was a disciplinarian dentist, his third Bulgaria's top composer and music teacher, Pancho Vladigerov. He gave his first public performance at the age of eight. In 1941, his mother together with Alexis tried to escape from German-occupied Bulgaria by walking over the frontier to Turkey, but they were caught and sent to a concentration camp in Bulgaria for three months. One day a German guard who liked music had heard Alexis play Schubert on the accordion. Without warning, the guard took him and his mother to the train station, put him on a train to Istanbul and threw the accordion through the window of their compartment as the train pulled away. They safely arrived in Istanbul, Turkey. In 1945, they emigrated to Mandate Palestine, where he studied music at the Jerusalem academy of Music and performed Beethoven with the Israel Philharmonic under the direction of Leonard Bernstein. In 1946 he went to the USA and the following year he made his New York debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra playing Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 3. Between 1957 and 1966 he took an extended sabbatical for the purpose of studying and teaching. After touring extensively the USA and Europe, Alexis Weissenberg moved in 1956 to Paris, eventually becoming a French citizen.

Weissenberg resumed his career in 1966 by giving a recital in Paris; later that year he played Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1 in Berlin conducted by Herbert von Karajan, who praised him as "one of the best pianists of our time". He further enhanced his reputation with performances of Chopin, Brahms and Stravinsky. Weissenberg gave piano master classes all over the world. His Piano Master Classes in Engelberg, Switzerland, attracted many young pianists.

Alexis Weissenberg's recording of the Franz Liszt Sonata of the early 1970's is one of the most exciting and lyrical in a discography with at least 75 recordings. He was also a composer of piano music and a musical, Nostalgie, which was premiered at the State Theatre of Darmstadt in 1992.

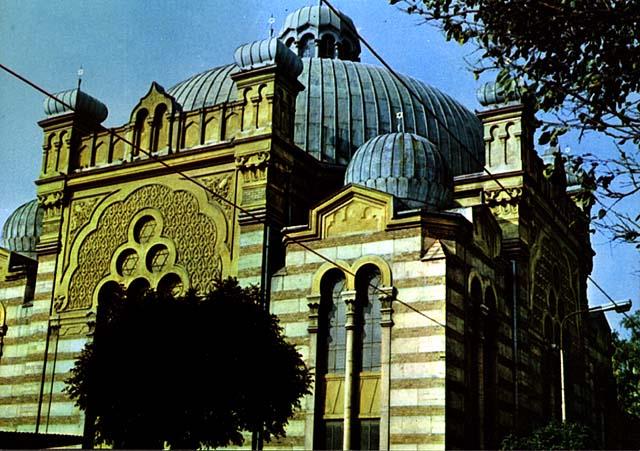

The Great Synagogue, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1960-1970. Postcard

(Photos)Postcard

It was sent as a Rosh Hashana card by Yoseph Levi from Sofia, Bulgaria

The synagogue was badly damaged during World War II and renovated by the authorities. It was declared a national monument.

The synagogue was built between 1905-1910, the architect was the Austrian Friedrich Grunanger. The synagogue had 1,170 seats and was built in Moorish-Vienese style. Today there are only a few people that come to pray in a small room in the synagogue where a small Judaica collection is kept

The Jews of Sofia during a convention in memory of the death of Dr. Theodor Herzl, Sofia, Bulgaria, July 7, 1904

(Photos)the death of Dr. Theodor Herzl, Sofia, Bulgaria, July 7, 1904

The procession was attended by rabbis and leaders of the community. The Maccabi flag, with a black ribbon attached to it, is carried by Emmanuel Nissimov, a prominent member of the community, head of Maccabi Sofia and chairman of Keren Hayesod in Bulgaria

(The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot, courtesy of Nissim Nissimov, Tel Aviv)

Medical students (Jews and not Jews) in Sofia, Bulgaria, September 1942

(Photos)of medical students (Jews and not Jews), interns

in a hospital in Sofia, Bulgaria, September 1942

In the hospital the Jewish interns were not forced

to wear the Yellow Badge

(The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot,

courtesy of the Uziel family, Israel)

Men of the Nissimov Family. Sofia, Bulgaria, c.1877

(Photos)Sofia, Bulgaria, c.1877.

The photograph dates back to a time before there was a proper family name. Emmanuel was known as Kasak. Later the family took on the family name Nissimov, (son of Nissim).

(The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot, courtesy of Nissim Nissimov, Tel Aviv)