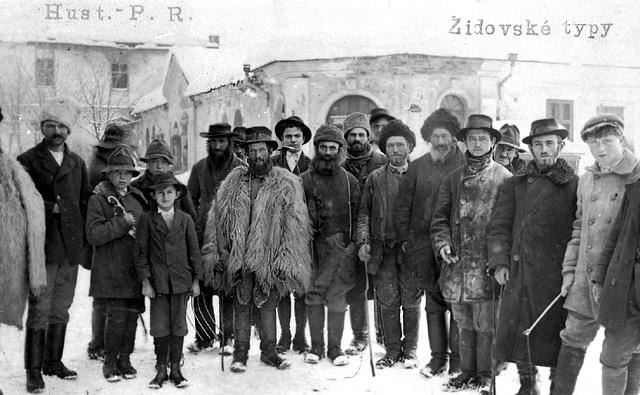

The Jewish Community of Khust

Khust

Хуст; Czech: Chust

A town in the historical region of Ruthenia in Zakarpattia Oblast, Ukraine. Until 1918 it was part of Austria-Hungary, between the two world wars in Czechoslovakia and during WW II annexed by Hungary.

The Jewish community established in the middle of the 18th century numbered 14 families in 1792. Jacob of Zhidachov was appointed as the first rabbi in 1812. In the mid-19th century, the community became one of the largest and most important in northern Hungary, mainly through the authority of the orthodox leader, Moses Schick, rabbi of Khust from 1861 to 1879. Most of the orthodox rabbis in Hungary were trained in his yeshivah, which had some 400 students. His successors, Amram Blum, and Moses Grunwald (1893-1912), prevented the development of chasidism in the community.

Under Czechoslovakian rule (1920-38), Khust had an active Jewish party in 1923. The rabbi of the town from 1921 to 1933 was Joseph Duschinsky, later rabbi of the separatist orthodox community of Jerusalem. The number of Jews living in the town was 3,391 in 1921 and 4,821 in 1930; in that same year 11,276 Jews (15.8% of the total population) lived in the Khust district.

The Jews of Khust were among the first to suffer when the area came under Hungarian rule in 1938. Jewish men of military service age were forced into the labor battalions. In 1942 there were approximately 100-130 yeshivah students in Khust. About 10,000 Jews from the town and district were concentrated in a ghetto in the spring of 1944, and from there deported to the Nazi death camps. In April 1944 the town was declared Judenrein. After World War II the community was revived.

In the late 1960s the authorities permitted a synagogue to open in Khust, the only one in the district, and the community had a shochet. At the time the number of Jewish families in the town was estimated at 400.