The Jewish Community of Zliten

Zliten

Arabic: زليتن

A town in the Murqub District of Libya

HISTORY

A Jewish settlement existed in Zliten in the 2nd century, during the Roman period. It ceased to exist during the period of the Muwahidun dynasty, which persecuted the Jews during the 12th and 13th centuries the extremist Islamic dynasty in the 12th and 13th centuries and led to the destruction of the Jewish communities in North Africa. The Jewish settlement in Zliten was revived in the 16th century, after Spain occupied Tripoli in 1510 and many of Tripoli’s Jews escaped to Zliten.

More specific information about the Jews of Zliten is available from the period of the Karamanali dynasty (1711- 1835), which ruled the area under the auspices of the Ottomans. During this period Zliten’s Jews worked in the oil and date trade. Following the establishment of direct Ottoman rule in 1835, more Jews arrived at Zliten and settled in streets near the governor’s palace, outside the Muslim Quarter. Many Jews began working in the esparta (also known as halfah; a type of grass in north Africa and southern Europe) plant, which was used to manufacture paper.

The community’s income came from the taxes on kosher slaughter and kosher wine, and from money donated by those who were called up to the read the Torah. Additional income came from the annual Lag Ba-Omer celebrations around the synagogue Bu-Shaif. So many people participated in these celebrations that the community rented two buildings to accommodate visitors.

The relationship between Zliten’s Jews and their Muslim neighbors was fraught, with tensions based on religious and economic differences. The town’s Muslims strongly resented the commercial relations between the Jewish and European merchants. Meanwhile, religious tensions grew around the synagogue Salat Bu-Shaif; Salat Bu-Shaif became a pilgrimage site, and it was located near the tomb of Sidi Abd Al-Salem, a sacred site for Muslims. Tensions reached a climax when the synagogue was set on fire in 1867. A cornerstone for a new building for the synagogue was laid in the 1870s, after sustained pressure on the authorities in Istanbul.

However, the new building did not spell peaceful times for Zliten’s major synagogue. In 1897 the synagogue was looted, and in 1903 another attempt was made to set the building on fire. The synagogue was eventually burned down again, in 1915. It was rebuilt in 1918 with the help of the Italian authorities, as well as Nahum Khalafu, one of the prominent members of the Jewish community of Tripoli. Once the new synagogue building was built, the annual pilgrimage to the Bu-Shaif synagogue became an established tradition.

In 1906 Prof. Nahum Slouschz visited Zliten. He reported that the local Jews worked mostly as artisans, while the wealthier members of the community worked in trade. The head of the community during the early 20th century was Saul Shtiwi; he was assisted by a number of notable members of the community, including Shalom Zanzuri, the clerk of the managing committee. The managing committee itself was formed in the Ottoman period, and during the Italian period it consisted of five members. The last head of the community before the Italian occupation was Moshe Rubin. Rubin’s successor, Huwato Salhub, was appointed by the Italians in 1918, and he served until 1935, when he was succeeded by Hai Glam. Rabbis who served the community from the end of the Ottoman period included David Salhub, Huwato Ganish, and Jacob Kahlon. Makhluf Shakir of Msellata, was the community’s last rabbi, and served until the community dissolved.

Community institutions included two synagogues (including the Bu-Shaif synagogue), as well as a Talmud Torah that enrolled 45 students. There was also a chevra kaddisha, the Chevrat D’Rabbi Gershon; among its activities was building a wall around the Jewish cemetery in the 1930s. Charitable organizations included Ezrat Evionim, Hachnasat Kallah to provide for poor brides, and Chevrat Shirei David, a boys’ choir that sang psalms in public events that was established in the 1930s under the auspices of the Talmud Torah.

During World War I (1914-1918), Arab insurgents attacked the town and looted Jewish property. The Jews evacuated Zliten under the protection of the Italians. They remained in a camp in the suburbs of the town, and returned to their homes only after the Italians reoccupied the town in 1918. Indeed, the economic and security situation of the Jews under the Italian regime improved significantly.

Most Jews worked as traders in dates, agricultural produce, and cattle during the interwar period. Others worked as peddlers, shopkeepers, artisans, moneylenders, and landowners. Wealthy and prominent families within the community included the Tayar, Shtiwi, Kahlon, Davosh, and Ganish families.

Zionist activity began in Zliten in 1934 with the establishment of the Ben Yehuda. Ben Yehudah was influenced by the Jewish community of Tripoli, and led by Hai Glam until his appointment as the head of the community. Glam was succeeded in his role at Ben Yehuda by Saul Shtiwi. By the end of the 1930s there were about 100 young people involved in the Zionist youth movement. They studied Hebrew and were involved in Zionist activities at their club.

WORLD WAR II (1939-1945)

In 1940, all Zionist activity ceased, as a result of fascist racial laws. Though only a few Jews from Zliten were conscripted for forced labor, the town’s Jews faced a number of restrictions. Many lost their jobs, and their children were not accepted into secondary school. As a result of the discrimination that they faced, most of the Jews left Zliten in 1942. They returned in 1943, after the British occupation, and a few began serving in the British police force.

The Ben Yehuda club reopened in 1943. Its activities included a drama circle, Hebrew classes, and hosting Jewish soldiers from Israel. Eventually Ben Yehuda joined the Brit Ivrit Olamit, the World Association for Hebrew, and Hebrew textbooks began arriving from Palestine. Another club, the Hebrew scouts, was founded in 1944.

POSTWAR

On November 5, 1945, a pogrom broke out against Jews throughout Libya, including Zliten. Though Zliten’s Jews were not physically hurt during the riots, a number of houses were looted or destroyed. In 1948, particularly after the establishment of the State of Israel, the relationship between the Jews and the local population deteriorated significantly. Most of Zliten’s Jews left for Tripoli in 1949. From there they continued to Israel, where they settled in Moshav Zeitan.

Rachel Dabush, Zliten, Libya, 2018

(Video)Rachel Dabush was born in Zliten, Libya. In this testimony she recounts her family's history, their sufferings during the Holocaust and later during the Arab attacks against the Jews. She describes her family traditions, their immigration to Israel, and her life in Israel.

-------------------------

This testimony was produced as part of Seeing the Voices – the Israeli national project for the documentation of the heritage of Jews of Arab lands and Iran. The project was initiated by the Israeli Ministry for Social Equality, in cooperation with The Heritage Wing of the Israeli Ministry of Education, The Yad Ben Zvi Institute, and The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. The film was produced as part of the Seeing the Voices project, 2019

Rachel Shalchov Recounts Her Family's History in Zliten, Libya, 2018

(Video)Rachel Shalchov was born in Zliten, Libya, in 1940, and immigrated to Israel in 1949. Rachel's father ran a tavern with liquor, backgammon and cards in the evening, and during the day he was a merchant - buying and selling goods in the wholesale market. They lived in the Jewish quarter (hara), an average family with 7 children. Women gave birth at home. They kept tradition, Shabbat, ate kosher food. They spoke Italian and the children also spoke Tripolitan Arabic. They went to an Italian school in the afternoon, and also studied Torah near the synagogue called Tzadika Busheif, which was considered a descendant of King David with virtues and miracles and people believed and prayed. They celebrated the holidays, Rachel remembers Pesach and Sukkot. The community was not large. She defines the relations with the neighbors as "respect them and be aware of them". During World War II, Rachel's father was friend to a policeman who warned against riots, so they fled to the Sahara Desert. Arabs hid them in a pantry and took care of them. Their house un Zliten became a Nazi camp. A year later they returned home. In 1945 there were riots in Zliten and Rachel's father hid hand grenades in the attic. In 1949, most of the Jews left Zliten. Rachel's brothers immigrated to Israel illegally. Aliyah emissaries arrived from the Land of Israel. They moved to Tripoli, where Rachel underwent treatment for ringworm. They sailed on ship Herzl to Israel, and upon arrival they were sent to the transit camp (maabara) in Be'er Ya'akov. The immigrants from Zliten organized themselves and settled in Moshav Zeitan and his son settled there permanently. The reception in Israel was fine, father was successful, and they recovered.

-------------------------

This testimony was produced as part of Seeing the Voices – the Israeli national project for the documentation of the heritage of Jews of Arab lands and Iran. The project was initiated by the Israeli Ministry for Social Equality, in cooperation with The Heritage Wing of the Israeli Ministry of Education, The Yad Ben Zvi Institute, and The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. The film was produced as part of the Seeing the Voices project, 2019

Leah Ashman Recounts Her Childhood in Zliten, Libya, 2018

(Video)Leah Ashman was born in the town of Zliten, Libya, in 1939 - approximately, since there was no accurate record of birth dates at the time, and she only knows that she was born between one brother and the other and this way she estimates her birth date. At the time Zliten was a very small village near Tripoli. There were no real professions for men, her father made a living selling silverware. The parents had 10 children, but four died. Leah was born prematurely, but managed to survive. They attended a Jewish school in the morning, and then an Italian school. In Zliten there was an ancient and special synagogue called 'Bou Shaif', where thousands come on Lag Ba'Omer. She remembers how they entertained crowds of people on the night of Lag Ba'Omer. When the emissary of the Aliyah, Baruch Duvdevani, arrived in Zliten, he was received with the honor of kings. Relations with the Arabs were excellent until 1948, when tensions grew. They tried immigrate to Israel, but because Leah had a trachoma in her eyes, they delayed the family for a year until she recovered, and only then did managed to immigrate. The voyage was difficult, and they were not allowed to take any possessions with them. She said that her father made new shoes for them and hid gold in their soles so that he would have something to help him start a new life in Israel. Upon arrival they were sent to Zarnuga transit camp (maabara). Her father had a very difficult time getting a job, and he died 3 years after arriving in Israel.

-------------------------

This testimony was produced as part of Seeing the Voices – the Israeli national project for the documentation of the heritage of Jews of Arab lands and Iran. The project was initiated by the Israeli Ministry for Social Equality, in cooperation with The Heritage Wing of the Israeli Ministry of Education, The Yad Ben Zvi Institute, and The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. The film was produced as part of the Seeing the Voices project, 2019

Simcha Natan Recounts Her Childhood in Zliten, Libya, 2018

(Video)Simcha Natan was born in Zliten, Libya, in 1938. At the time this was a village by the sea, with about 50 families, all of them Jewish. The Arabs lived around the village. The Jews of the village were mainly engaged in trade. Her last name before her marriage was Dabush - a very well-known family of rabbis in Zliten and its surroundings, and her mother belonged to Kachlon family, also a well-known family. Her father and mother had 10 children, two of whom died. During the Second World War she was a toddler, and does not remember. Only one story remained in the family from the war, a story that greatly influenced the whole course of life. The Italians ruled Libya, and during the war it was a Fascist-Nazi regime. One day a curfew was imposed on the village, and Simcha's father went out anyway. The soldiers caught him and took him to the police station, where they beat him for a whole night. If he passed out, they wake him up and continue. In the morning he was thrown out of the station, and his mother took him up home. Then he suffered from back pain and disabilities, and was unable to return to his work. The burden of livelihood was ever since was on the mother who made a living as a seamstress. The war ended at the end of 1942. Life in Zliten was a life of ease on the whole, and the relationships with the Muslims were stable and calm. Simcha went to the Hebrew school in the morning, and in the afternoon to the Italian school. The Zionist movement Ben Yehuda also operated in the village. One day, in 1945, without any warning, there were loud knocks on the house door. Simcha's father asked "Who is there?" And the answer was in the style of cursing and hate against the Jews. He immediately understood what was happening and locked the house. Simcha remembers a terrible fear. The Muslims in the entire district went on a rampage that day, murdering dozens of Jews, abusing women, looting and vandalizing. The Jews understood, and since then fear reigned in the village. People rarely went out, parents kept their children and limited their steps. In 1947, when the partition plan of British Mandate Palestine was decided by the United Nations, the Libyan Jews received an order to leave the country. Those who stay will do so at their own risk. Trucks came to Zliten, and the place was emptied of its inhabitants. The trucks took them to Tripoli, near the port from which ships left for Israel. They stayed there for about three very difficult years, all the Jews of the area, huddled in the already overcrowded Jewish quarter, waiting for their turn to immigrate. In 1951, they boarded the Galila ship, and settled in Moshav Zeitan. Since the father could not cultivate the plot of land allotted to him in the moshav, they were removed from the moshav a few years later and sent to Transit Camp # 3 in Ashkelon.

-------------------------

This testimony was produced as part of Seeing the Voices – the Israeli national project for the documentation of the heritage of Jews of Arab lands and Iran. The project was initiated by the Israeli Ministry for Social Equality, in cooperation with The Heritage Wing of the Israeli Ministry of Education, The Yad Ben Zvi Institute, and The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. The film was produced as part of the Seeing the Voices project, 2019

Ora Peled Speaks About Life in Zliten and Tripoli, Libya, and Her Immigration to Israel, 2018

(Video)Ora Peled was born in Zliten, Libya, in 1933. In this testimony she speaks about her family and recounts her childhood in Zliten and then the life in Tripoli, Libya, and Rome, Italy, before her immigration to Israel.

-------------------------

This testimony was produced as part of Seeing the Voices – the Israeli national project for the documentation of the heritage of Jews of Arab lands and Iran. The project was initiated by the Israeli Ministry for Social Equality, in cooperation with The Heritage Wing of the Israeli Ministry of Education, The Yad Ben Zvi Institute, and The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. The film was produced as part of the Seeing the Voices project, 2019

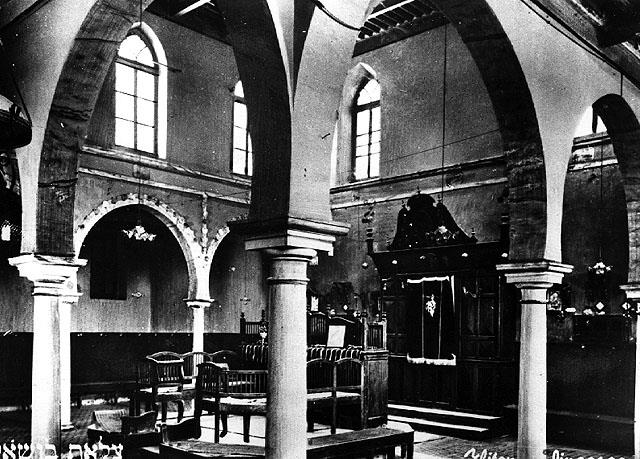

Interior of "Slat Abn Shaif" Synagogue in Zlitten, Libya 1920-1930. Postcard

(Photos)in Zlitten, Libya 1920-1930.

The synagogue was built more than 900 years ago. Jews from allover North-Africa used to make pilgrimage to this

synagogue on Lag Ba'Omer.

(The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot,

courtesy of the Cultural Center of Libyan Jews, Tel Aviv)

Msallata

(Place)Msallata

In Arabic:مْسَلَّاتة ; Msallata, also known as Qusbat or El-Qusbat

A town in the Murqub District, Libya.

The Jewish community of Msallata is on record as one of the communities that were ruined by the rulers of the dynasty of Muwahidun at the middle of the 12th century. The Jews of Msallata were exiled to the isle of Djerba (in Tunisia) and absorbed the customs of the Jews of Djerba.

During the 16th to the 19th centuries the trade with the Sahara flourished and Jewish merchants settled at Msallata, where they were greatly respected. At the beginning of the Ottoman period, in the 16th century, a Jewish community existed at Msallata. A synagogue named “Salat Simha” stood at a place called “Halfon”, the name of the rich Jewish family that built the synagogue. Many sites with Jewish names of that period were known around the town. Successive information as to Jewish settlement at Msallata is available from the middle of the 19th century. The traveler Benjamin II visited Msallata in 1833 and found there 150 Jewish families. The head of the community was then Pinhas Malu and Rabbi Moshe was the rabbi of the community. The synagogue of that time had been built in 1815. In 1886 the Jewish population increased and numbered 700 persons. Prof. Nahum Slouschz found at Msallata in 1906 700 Jews, but the state of the community was very poor because of the heavy taxation on the Jews. From the beginning of the modern community, most of the local Jews were petty traders, peddlers, and artisans, such as goldsmiths, tailors, blacksmiths and coppersmiths, and cobblers. There were also moneylenders. The women engaged in weaving and embroidery.

Regular community institutions functioned already by the end of the 19th century. The synagogue was the only big stone building of the community. It had been built in 1862 on the ruins of the former synagogue by two Jews from Tripoli. The community had a rabbi who was also the shohet (ritual slaughterer). There was no formal Talmud Torah but Hebrew lessons were given by the rabbi. The Jewish cemetery was looked after by the hevra kadisha. From the end of the 19th century the community owned two flourmills. The majority of the Jewish houses stood around the ottoman fortress and near the market.

The tomb of an unknown holy person, called Qubur al Hakham , was at Msallata. He was possibly an emissary from Eretz Israel and miraculous events were attributed to him. The tomb attracted both Jewish and Arab pilgrims. The community of Msallata had one tradition that was unknown in other Jewish communities of Libya. In the evening following the 9th of Ab they used to ride on donkeys to the cemetery, to welcome the messiah.

Following the Italian occupation of Libya in 1911 Jews evacuated Msallata. In 1917 only 450 Jews remained in the place. Then again, the Arab revolt against the Italians in the years 1915-1922 caused Jews to leave Msallata. When the revolt was suppressed, Jews returned to the town and in 1931 there were 342 Jews in the place. Most of them were poor and they lived in small single-storey houses, with no electricity. The community was managed by a committee, headed by a president. The committee was composed of the chief rabbi and another two or three members from among the rich families. Jehuda Atiyah was the president for many years, until 1930. He was the owner of agricultural land. He was succeeded by Mordechai Bibi Shakir, also an owner of land. He remained in office until the whole community emigrated to Israel in 1950. The income of the community came from the tax on kosher slaughter, from commercial taxes, and from the fee on being called up for the reading of the Torah in the synagogue.

The rabbi of Msallata at the beginning of the 20th century was rabbi Joseph Menahem. He was assisted by Rabbi Joseph Jarad, who was later the rabbi until 1939. Rabbi Jarad was followed by Rabbi Makhluf Shakir. In 1944 Rabbi Rahamim Legatiwi became the rabbi. All the rabbis performed, in addition, also the tasks of shohet (slaughterer), mohel (circumciser), darshan (preacher), hazzan (cantor) and melamed (teacher of small children). During all that period there was at the synagogue a Talmud Torah, which was attended by all the children of the community of the ages 6-13. Only religious subjects were taught at the Talmud Torah.

On the eve of World War II anti-Semitic articles began to appear in the local press. In 1940 a Jewish girl was kidnapped and later returned to her home. Following this incident, a pogrom against the Jews occurred. The synagogue was totally ruined by arson. The synagogue was never rebuilt and the public prayers were held at the house of Abraham Sumani, one of the rich persons of the community.

In 1943 the British forces occupied Msallata and the rabbi Makhluf Shakir obtained permission to establish a progressive Talmud Torah at the building of the Italian school which had been destroyed. The curriculum included also secular subjects, such as modern Hebrew and mathematics.

Another pogrom against. The Jews of Msallata occurred on November 5, 1945. The Arab rioters broke into the Jewish houses, looted property, destroyed the houses, and killed three persons - the former president Jehuda Atiyah and his brother Rahamim, and Said Legatiwi, the rabbi’s father. Jews were also forced to convert. Following this event most of the Jews of Msallata moved to Tripoli and Khoms, and only a few remained. In 1950 also these last ones left to Tripoli, on their way to Israel

Khoms, Libya

(Place)Khoms

Also known as Al Khums; Arabic: الخمس

A city on the Mediterranean coast in the province of Tripolitania, northwest Libya.

HISTORY

Khoms is located near the ruins of the Roman town Lebda (formerly the Phoenician Leptis Magna), a port that served the entire region. The Jews came to settle in Lebda from Israel, Mesopotamia, and Alexandria during the post-Second Temple Period. Additionally, the Roman emperor Septimus Severus (193-211) brought Jews to Lebda from Tripoli and allowed them to hold important positions there. A well-developed Jewish settlement is recorded during the Roman period, beginning in the 2nd century.

Lebda’s Jewish settlement continued to flourish during the period of Muslim occupation, and through the 11th and 12th centuries there were wealthy Jews who traded across the Sahara. In records found in the Cairo Genizah, Jewish merchants, mainly from Lebda, are mentioned, and referred to as Al-Labadi. The Jewish settlement of Lebda ceased to exist at the end of the 12th century, possibly as a result of persecutions by the rulers of the Al-Muwahidun dynasty.

Another Jewish settlement was established at the end of the 18th century, this time in Khoms. Jewish merchants, mostly from Tripoli, settled there and renewed the local trade in the halfa (esparto) plant. Muslims cultivated the plant inland, while the Jews arranged for it to be delivered to Khoms, where they processed and exported it, mostly to Britain, for the paper industry.

Following the 1835 Ottoman occupation, Jewish settlement was revived in a number of places throughout Libya, and the Jewish community of Khoms became well known in the second half of the 19th century for its economic activity. Most of the Jews who had arrived from Tripoli in search of better economic opportunities became successful merchants. In fact, local trade was dominated by the Jews, and on Shabbat all economic activity ceased. Jews were also engaged in traditional crafts, and some worked as blacksmiths, tinsmiths, silversmiths, goldsmiths, tailors, cobblers, and carpenters.

The community had one small synagogue in the attic of a rented Muslim house. At the end of the 19th century Mas’ud Nahum led the building of a new synagogue, which was completed in 1905 by his brother Raphael Nahum. The new synagogue was richly decorated, with marble floors and columns, and the Ark was carved in wood by master craftsmen from Malta. The building also included a study room and a guest room for visitors from Israel. Additional community resources and institutions included a cemetery, which was consecrated at the beginning of the 19th century, and a charity organization that functioned under the auspices of the Bikkur Holim Society.

In 1886 there were 150 Jews living in Khoms. By 1902 that number had grown to 300.

The community flourished during the Italian occupation (1911), particularly after two businesses for processing the halfa plant were established by two Jews from the Nahum and Hasan families. One Jewish family, the Dgedegs, worked in farming.

Prominent members of the community appointed a committee that managed the community’s affairs. In 1906 the head of the committee was Khamus Mimon, who held the title of Hakham Bashi (chief rabbi). During the period between the two World Wars the heads of the managing committee were Emilio Baranes, Saul Mimon, and Shimon Hasan.

The community’s income came from the tax on kosher slaughter, donations, contributions from people called up for the reading of the Torah, and from a tax on imported merchandise (a special Khoms tax).

Khoms’ Jewish community employed a rabbi, a shohet (kosher butcher), a hazzan (cantor) and a melamed (teacher of children). In 1928 Rabbi Frija Zuertz was sent to Khoms from Tripoli to serve as the community’s rabbi and Hebrew teacher. He occupied the post for twenty years, and was very influential on the Jewish education in Khoms.

Among Rabbi Zuertz’s activities was initiating Zionist activities in Khoms at the beginning of the 1920s. Susu (Joseph) Baranes became the local representative of the Jewish National Fund, and in 1926 Moshe Zuertz came from Tripoli to Khoms to raise money for JNF. In 1934 Rabbi Zuertz established a local branch of Ben Yehuda in order to spread knowledge of Hebrew and information about Palestine. Ben Yehuda operated out of Khamus Mimon’s house, and the club held evening classes, holiday parties, and theatrical performances—Rabbi Zuertz himself wrote some plays for the club’s drama circle. A local branch of Gedud Meginei Ha-Safah (Hebrew Language Protection Legion) was founded in 1936.

During the 1930s the Italian authorities began placing increasing restrictions on the Jewish population. The authorities decreed that shops were required to be open on the Sabbath, and attempted to restrict the teaching of Hebrew.

WORLD WAR II (1939-1945)

Khoms’ rabbi was imprisoned following the outbreak of World War II. The bombing of Tripoli and the surrounding areas led to a food shortage, and the Italian authorities instituted rationing. The community’s managing committee extended help to the poor.

The Italians issued a decree in June 1942 conscripting Jewish men for forced labor. Several dozen men were taken from Khoms to the Sidi Azaz camp, which was located about 6 miles (10 km) south, for work connected with the war.

Once the British occupied Khoms the socioeconomic situation of the Jews improved. A Jewish unit of the British Army from Palestine was stationed at Khoms, and its soldiers became involved with the community, including courses to study English.

In 1945 anti-Jewish riots broke out in Tripoli. Fearing that the riots would spread to Khoms, the Torah scrolls were moved from the synagogue and hidden in a church.

POSTWAR

The situation of Khoms’ Jewish community deteriorated after the war. Most of the Jews immigrated to Israel between 1950 and 1951.