The Jewish Community of Oran, Algeria

Oran

In Arabic: وهران

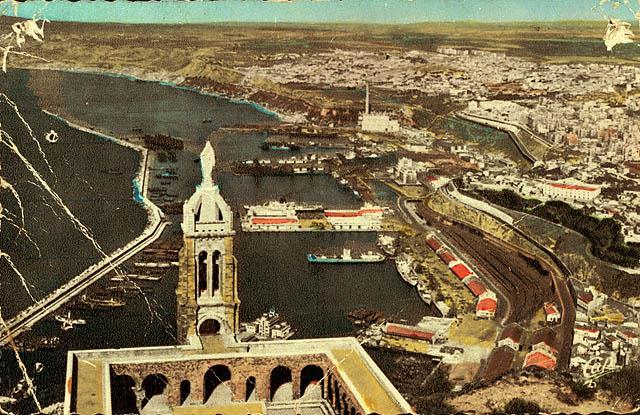

A seaport on the Mediterranean, Oran is the second largest city in Algeria and a major trading and industrial center. Called Wahran (also spelled Ouahran) in Arabic, Oran is located in Western Algeria near the border with Morocco at a point where Algeria is closest to the Spanish coast. Founded in the 10th century by Andalusian merchants, Oran was incorporated into the Kingdom of Tlemcen and served as its main seaport after 1437.

The Beni Zian rulers of Tlemcen, unlike the Almohades that preceded them, displayed a more favorable attitude towards the Jews and invited them to settle in their kingdom probably already in the early 14th century. However, the first mention of a Jewish community in Oran dates from 1391, when Jewish refugees arrived in the city having escaped the anti-Jewish persecutions in Spain. A discussion about the customs of the local Jews is one of subjects of the correspondence conducted by Rabbi Amram ben Merrovas Ephrati of Valencia, who settled in Oran, with Rabbi Yitzhak bar Sheshet (Ribash) (1326-1408) and Rabbi Shimon ben Semach Duran (Rashbatz) (1361-1442), both Spanish refugees from Barcelona and Majorca respectively, who moved to Algiers. The Jewish population of Oran increased towards the end of the 15th century with the arrival of immigrants from Spain. In 1492 and again in 1502 Oran received groups of Spanish refugees, both Jews and Muslims, fleeing from forcible conversion to

Christianity.

In 1509 Oran was captured by Spain in a military campaign launched at the initiative of Cardinal Ximenes (Jimenes) de Cisneros (1436-1517), the Archbishop of Toledo. Although the first intention of the Spanish troops was to expel the Jews from the city, it was not long before a few families were allowed live in the region. Oran remained under Spanish dominance for most of the next three centuries. While in Spain and its colonies there was a total ban on Jewish presence and crypto-Jews were persecuted by the Inquisition, in Oran the Spanish monarchs tolerated for much of the 16th and 17th centuries the existence of a small but influential Jewish community. Thus the small Spanish enclave of Oran along with the nearby port of Mers el-Kebir remained the only place in which the old Spanish conviviencia of Christians, Muslims and Jews continued for another century and a half. A list from 1530 mentions about one hundred twenty five Jews of Oran as enjoying the protection of the King of

Spain and another seventy two Jews who lived in the area and who did not enjoy the same legal status. Additional lists from 1591 and 1613 mention about one hundred twenty five and two hundred seventy seven Jews, respectively. The Jewish population stayed within the same limits for most of the first half of the 17th century, including a number of "foreign" (forasteros) Jews who were permitted to reside in the Spanish territory. The Jews of Oran lived in a distinct district of the city where they had a synagogue and continued the practice of Judaism openly. They also maintained relations with other Jewish communities in North Africa and around the Mediterranean. These relations along with a knowledge of both the Arabic and Spanish languages turned into important assets that contributed to the commercial success of the Jews of Oran. Their contribution to the local economy as agents and mediators between the Spanish enclave and the Muslim hinterland assured them the protection of the

royal authorities against the Inquisition. Much of the economic and political power of the Jewish community was concentrated in the hands of a few dominant families. They included the Bensemero (also spelled Benzemero, Bencemerro or Zamirrou) family, and especially the Cansino family, originally from Seville, who were among the residents of Oran when the city was captured by the Spanish in 1509, and the Sasportas family who reportedly came to Oran from Barcelona. Although intermarried, the Cansino and the Sasportas families maintained a strong rivalry for generations; this conflict attracted the interference of the Spanish authorities and probably contributed to their decision to expel the Jewish community of Oran.

In 1669 the Spanish Queen Maria of Austria decided to expel all the Jews of Oran and its vicinity. The Jewish population, estimated at about 450 persons, was given eight days to leave the city. They traversed the Mediterranean for Nice, then under the control of the Dukes of Savoy, and from there some continued to Livorno, in Italy, where they joined the local Jewish community. The synagogue of Oran was converted into a church. Jews could return to Oran only in 1708, when the Muslims led by the Bey of Mascara, Mustapha ben Yussef, also known as Bou Shlahem captured the city. The Spanish rule returned to Oran in 1732 and it appears that some Jewish individuals were permitted from time to time to enter Oran and even sojourn there. On the night of October 8/9, 1790, Oran was destroyed by a catastrophic earthquake that caused thousands of casualties. The Spaniards were not interested in rebuilding the city; two years later Spain abandoned Oran and passed it on to Mohammed el Kebir, the

Bey of Algiers. The city suffered even more when the remaining population was decimated by a plague epidemic in 1794.

Following the restoration of the Muslim governance over Oran, the Jews from the neighboring city of Tlemcen, as well as from Mostaganem, Mascara, and Nedroma responded to the invitation of the Bey of Algiers and settled in Oran. The emerging Jewish community brought a quarter of the town close to Ras el-Ain and was granted land for a cemetery in the district of Sidi Shaaban. The rights of the Jewish community are detailed in an agreement of 1801 that also mentions the names of its leaders: Ald Jacob, Jonah ben David, and Amram. At the same time Rabbi Mordechai (Mardochee) Darmon (c.1740-c.1810), who came from the Jewish community of Mascara, became the mokdem ("president") of the local community. In addition, Mordechai Darmon played an important role as counselor of the bey (Turkish governor) of Mascara and of the bey of Algiers. He established the synagogue that later was called after him and was the author of Maamar Mordechai ("Sayings of Mordechai"), a biblical commentary

published in Livorno in 1787. During the early years of the 19th the Jewish population of Oran grew with the arrival to the city of Jews from other cities in Algeria and Morocco who were attracted by the new commercial opportunities between Oran and the ports of the Iberian Peninsula - Gibraltar, Malaga, Almeria, as well as Italy and southern France.

The Jewish community was governed by a mokdem (or mukkadem, a term that sometimes was understood as being the equivalent of the Hebrew title of nagid, head of the Jewish community) who was assisted by a council called in Hebrew "tovey-ha'ir". The mokdem was named by the bey and his main task was to represent the interests of the Jewish community in its relations with the Turkish authorities. The mokdem was responsible with the payment of the taxes by the Jewish community and he enjoyed an extensive authority over the community. He named the other members of the community leadership, controlled their activities, and raised new taxes. The mokdem was assisted by a sheikh whose authority was limited; his main prerogative was to make sure that the decisions of the mokdem and of the other leaders of the community were implemented and respected and that the community members kept their religious and social duties. All disputes among the community members, including marriages and divorce,

were decided by the dayanim (religious judges), with the exception of criminal matters or disputes between Jews and Muslims, who were decided by a caid (Muslim judge).

The security of the Jewish community in Oran was sometimes threatened by political rivalries between the local Muslim leaders and the central Turkish authorities in Algiers, and by the growing interference of the European powers, especially France. In 1805 many Jews of Oran fled to Algiers fearing the aftermaths of a local rebellion. In 1813 some Jews who sided with a local pro-French rebellious bey were executed and other families were deported to Medea, when Oran returned to Turkish central control. In July 1830 Oran was secured by the French troops who prevented a Turkish plan of massacring and deporting the local Jewish population. The event, who later was remembered as the Oran Purim, inspired the piyyut Mi Kamokha ("Who is like You?") by Rabbi Messaoud Darmon (d.1866), grandson of Rabbi Mordechai Darmon. The Jewish community of Oran used to commemorate the Oran Purim by reading the piyyut in the city's synagogues every year on Shabbat before the 9th of Av.

At the time of the French entrance to Oran in 1831 the great majority of the city population was Jewish. According to a census conducted by the French there were about 2,800 Jews in Oran, well ahead of the local Christians and Muslims who together amounted to about 1,000 inhabitants. Under the French rule that lasted until the Algerian independence in 1962, Oran turned into a modern port and the adjacent strategic town of Mers el-Kebir became a major naval base.

The French administration abolished the old system of government of the community and instead the French system of consistoire was introduced. The Jewish community was governed by a Grand Rabbin and a president. A Beth Din (Jewish religious court) was established by the French in 1836; it functioned for five years under the presidency of Rabbi Messaoud Darmon before it was canceled by the French authorities. Messaoud Darmon became Grand Rabin of Oran in 1844 and kept this title until his death in 1866. The religious tradition of Oran is expressed in its own mahzor (book of prayers): Mahzor Wahran.

After 1860 the number of Jews in Oran augmented with the arrival of new Jewish settlers, mainly refuges from Tetuan in Morocco who fled the ravages of the Spanish-Moroccan war of 1859-1860. By the mid 19th century there were about 5,000 Jews in Oran. The community was administrated by a consistoire that had a president and some ten members elected from the local notables. The religious functions were performed by a Grand Rabbin. A report from 1850 mentions another sixteen rabbis, three dayanim, and three shochatim (ritual butchers). During the mid 19th century there were seventeen synagogues in Oran; of them only one belonged to the community while the others were private foundations run by the descendants of the original donor who decided who could attend them. The community was administrated by a number of committees charged with collecting money for the maintenance of the Talmud-Torah and assistance for the needy members of the community. A separate Gemiluth Hassadim organization

was in charge of the funerals and assisted the family members during the mourning period. One of the committees was headed by a rabbi and was in charge of the local education. There were about twelve traditional schools that were attended by about 550 students. The first French school was opened in 1849 and by the mid 19th century attracted around 100 students. The beginnings of the Jewish press in Oran are the result of the efforts of Elie Karsenty who started the publication of the weekly La jeunesse israelite in French and Hebrew followed by Magid misharim, a Judeo-Arabic weekly. Moise Setrouk was the director of La voix d'Israel, the monthly official bulletin of the Association culturelle israelite du department d'Oran.

A major change in the legal status of the Jews of Oran, and indeed of the other Jewish communities of Algeria, resulted from the implementation of the law of October 24, 1870, generally known as the Cremieux Decree after Adolphe Cremieux (1796-1880), the Jewish French Minister of Justice at the time. The Cremieux Decree granted full French citizenship to all Jewish inhabitants of Algeria. Four years later the law was restricted to only those Jews who either they or their parents were born in Algeria before the French conquest of 1830. French citizenship gave all male Jews the right to participate in the local municipal elections. Given the high percentage of Jews in the general population of Oran and its region, the newly acquired French citizenship transformed the Jews into an important electoral force. Their electoral impact was even stronger as they generally voted homogenously at the instructions of their leaders, such as Simon Kanoui (d.1915), president of the Consistoire of

Oran for many years and sometimes nicknamed the "Rotschild of Oran", who declared publicly on a number of occasions that nobody would be elected mayor of Oran without his support.

During the second half of the 19th century the Jewish population of Oran consisted of a number of distinct groups. The majority were descendants of the initial settlers who came from Mostaganem, Mascara, Nedrona, and Tlemcem. Together with the group made up of later immigrants from Algiers, the villages of the Rif region and the towns of Oudja, Dedbou and the oases of Figuig and Tafilalet, they were known as the "Jews of Oran". They distinguished themselves from the group of immigrants from Tetuan and especially from other Jews who arrived in Oran from France and other countries of Europe. The Jews of Oran spoke a variety of languages: those of Algerian origin continued to use local dialects of Judeo-Arabic; Tetuani, the name of the Oran dialect of Hakitia, the North African version of Ladino, was spoken mainly by immigrants from Tetuan, but the great majority of Jews had gradually adopted the French language. The construction of the Great Synagogue started in 1880 at the initiative

of Simon Kanoui, but its inauguration took place only in 1918. Also known as Temple Israelite, it was located on the former Boulevard Joffre, currently Boulevard Maata Mohamed El Habib. The religious education was advanced by a local Beth Midrash. In the early 1900's Yeshivat Vezoth LeYehudah was founded in Oran with the help of Yehudah Hassan and of Simon Kanaoui. It continued to function into the first half of the 20th century under the leadership of Rabbi David Cohen-Scali (1861-1947) and was attended by other rabbis of Oran.

The occupational structure of the Jewish population of Oran changed gradually in the period starting with the end of the 19th century. If by 1900 the majority of Jews were still traditional artisans – tailors, goldsmiths, shoemakers, bakers, cabinet makers – and unskilled laborers, later during the first half of the 20th century as a result of better education many entered the liberal professions. There were also some women who worked outside home as dressmakers, domestic workers, and typists. It is worth mentioning that the first vineyards in the neighborhood of Oran were planted and owned by Jews. Jews were prominent among the shopkeepers of the city and dealt with a large variety of merchandise. A number of prominent Jews of Oran continued the long established commercial links their ancestors developed for centuries with the neighboring countries and many were engaged in the export of cereals and cattle to the Spanish ports of Malaga, Cartagena, and Algesiras as well as to the

British colony of Gibraltar and to France.

Already by the mid 19th century, Oran had developed an anti-Jewish atmosphere. Old anti-Jewish bias brought to Oran by devout Catholics settlers from Spain and France were exploited frequently by local politicians. The first anti-Jewish organization was founded in July 1871 as a direct reaction to the granting of French citizenship to Jews. Anti- Jewish attacks in the local press and even anti-Jewish physical violence preceded by almost two decades the riots exacerbated by the outbreak of the Dreifuss affair. The anti- Jewish campaign had many supporters in Algeria, especially in Oran, and it brought to an aggravation of the anti-Jewish sentiment prevalent among many European settlers in Algeria. Anti-Jewish riots broke out in Oran in 1897 after the electoral victory of the "French Party". In May 1897 the Jewish quarter and many Jewish shops were attacked by both European settlers and local Muslims. Several Jewish policemen were laid off and Jewish patients were expelled from public

hospitals. However, the French authorities refused to cancel the Cremieux Decree which was the principal demand of the anti-Jewish parties and organizations. The anti-Jewish incitement declined after 1902, when the radical anti-Jewish party lost the municipal elections, but Oran remained a major bastion of anti-Semitism in North Africa.

Although massive Jewish support and participation in WW1 helped to calm the attacks against the Jews, anti-Semitic attacks returned during the 1920's only to worsen in the late 1930's. In 1936 there were new violent attacks against Jews in Oran and its department. When France was defeated by Germany in June 1940, Algeria remained under the jurisdiction of the pro-Nazi Vichy government. The introduction of anti-Semitic legislation followed shortly: in October 1940 the Cremieux Decree was abolished and the Jews of Algeria lost their French citizenship. In March 1941 the racial laws of the Vichy government started to be implemented in Algeria. Jews were expelled from all organizations and associations; they were denied the practice of liberal professions – physicians, lawyers, realtors, insurance agents, nurses, chemists, teachers and educators. Jews were allowed to teach only in Jewish educational institutions, like Alliance Israelite Universelle. Jewish children were expelled from

elementary and secondary schools, and the number of Jewish students was set up at three percent. Some Jews, especially young students, joined the anti-Fascist Resistance.

In 1942 the Jewish community of Oran sheltered a group of 150 Jews from Libya that had been deported by the Italian Fascist authorities. The landing of the American troops in November 1942 in Oran, one of the main objectives of the Allied invasion of North Africa, ended the anti-Jewish persecutions. Although the racist laws were cancelled relatively quickly, the appointment as Governor of Algeria of Marcel Peyrouton, a former minister of the interior in the Government of Vichy and signatory of the anti-Jewish laws of 1940, delayed the restoration of the full civic rights of the Jews. The Cremieux Decree was reintroduced only one year later, in November 1943, when Charles de Gaulle took over the control of Algeria and after direct intervention from the American administration. Some Jews joined the Allied armies, especially the military units of Free France and participated in the invasion of Corsica and then of southern France, at Toulon, as well as in the campaign in Italy.

The years that followed WW2 saw the breakout of the Algerian struggle for independence. After 1954 the conflict between the Muslim population of Algeria and the European settlers turned into an increasingly violent struggle. The Jews strove to remain neutral as much as possible, but soon they too were entangled into the war only to become targets for both the Algerian and French nationalists. Oran, that in the early 1950's had a majority of European population, was spared for some time from the violence. The city's Jewish community of almost thirty thousand people continued its regular life, but in February 1956 rioters attacked Jewish property. The attacks worsened in gravity and not before long they claimed casualties from among the Jewish inhabitants of Oran as well. The following years were marked by a gradual deterioration of the security situation; it worsened considerably at the end of 1960 when the Jewish cemetery of Oran was desecrated. The early 1960's brought about a

sharp decrease in the number of Jewish inhabitants of Oran. According to the Evian Accords that ended the Algerian war, the Jews were considered European settlers. Legislation adopted by the newly independent Algeria granted Algerian citizenship only to those residents whose father or paternal grandfather were Muslims. Moreover, the Supreme Court of Justice of Algeria declared that the Jews were no longer under the protection of the Law. The great massacres against the European population in June 1962 brought about the immediate exodus of the Jewish community of Oran during the following months. In 1963, a year after Algeria gained its independence from France, there were only 850 Jews left in Oran. In February 1964 a General Assembly of the Jewish Communities of Algeria was held in Oran. The worsening economic situation brought about by anti-Jewish boycott and other discriminations only strengthened in late 1960's. The departure of the few Jews left in Oran continued throughout the

decade with less than 400 still living in the city in 1968. The great majority emigrated to France with Israel as their second main destination. The Great synagogue was converted into a mosque in 1975. In the early 2000's apparently there were no Jews living in Oran.

Saadiah Ben Maimun Ibn Danan

(Personality)Saadiah Ben Maimun Ibn Danan (15th century), linguist, philosopher, poet and halakhist. Saadiah Ben Maimun Ibn Danan was born in Granada, Spain. He served first there and later, after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, in Oran, Algeria, as dayyan. Several of his responsa include some very important information. His treatise “The Necessary Rule of the Hebrew Language” (written in Arabic) deals, among other things, with Hebrew prosody and was the first attempt at comparing the Hebrew meter with the Arabic. He also wrote a talmudic lexicon and a Hebrew dictionary in Arabic. In his poetry, he continued the tradition of his great predecessors in Muslim Spain and like them, composed poems which reflect the beauty of the language. He did not reject secular poetry. One of his poems was written in honour of Maimonides’ Moreh Nevukhim (Guide of the Perplexed). He died in Oran, Algeria.

Claude Rouas of Napa Valley, CA, and a Native of Oran, Algeria, Recounts His Life

(Video)Claude Rouas was born in Oran, Algeria in 1936. Orphaned at a young age, Claude was raised by extended family including his uncle “Papa Isaac”, and his brother, who was the eldest of 5 siblings. After years of hard work in Oran, Paris and San Francisco, Claude eventually became one of Northern California’s most successful and important figures in the hospitality industry. He developed Napa Valley by building the famed Auberge Du Soleil Hotel and numerous restaurants in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Claude Rouas was born in Algeria in 1933. Orphaned at a young age after both of his parents died of cancer, Claude was raised by extended family including his uncle “Papa Isaac”, and his brother, who was the eldest of 5 siblings. Growing up in poverty and without parents, Claude learned the art of hard work early on. His childhood jobs included selling movie tickets, pedaling goods on the street, tailoring and working as a pastry chef. He lived on an all-Jewish street in the city of Oran, bordering an Arab Muslim neighborhood. Claude recounts some fights between the groups, but overall he remembers Jewish-Muslim relations during this time as peaceful.

Claude’s family migrated from Algeria to France in 1937 in hopes of finding better opportunities and a more secure life. Their first home in Paris was a store they rented, sleeping in the storage room and using the storefront as a makeshift dining room. They returned to Algeria in 1941, where Claude remained until moving to the U.S. in 1963.

Though he doesn’t come from an observant background, Claude was raised with a value of preserving Jewish tradition, and recalls fondly practices from his childhood such as studying for his Bar Mitzvah and going to synagogue on Passover. Every Friday evening his family gathered together for a Shabbat meal of couscous and d’fina stew. Jewish custom was an integral part of mourning and life cycles growing up.

The holiday of Yom Kippur holds significant meaning and memory for Claude. He remembers the hunger-fueled intensity and sullen temper of his congregation members at La Grande Synagogue d’Oran, some of whom even passed out at services. But Claude still looked forward to the holiday every year for a different reason. As it is customary to don new clothing for Yom Kippur, it was a busy time of year for the 9-year-old tailor. Working longer hours than usual, Claude stayed at his boss’s house for extended periods of time. Here he was guaranteed a cup of hot coffee and a slice of bread & butter every morning – a luxury that felt like “a dream life”. Nowadays Claude feels even closer to his faith, which he expresses through practices including lighting Shabbat candles weekly and wearing tallit. One of the most profoundly sentimental mediums that invoke Claude’s memory is the French-infused Jewish Algerian music. Ingrained in Claude’s mind are the lyrics of Enrico Macias, which intone stories of Jewish expulsion and migration to France. The melodies bring up such strong emotions of longing that he avoids listening to them altogether.

At the age of 14, Claude took a major step towards a more promising future when he left his family to attend a hotel and restaurant school. As the only Jewish student, he faced some of his most marked experiences of anti-Semitism the hands of his teacher, Monsieur Soleil, who was the head of the dining room department. Mr. Soleil had cordial relationships with other students in his department, who were 90% Arab Muslim, but with Claude he was physically and verbally abusive, asserting that Claude didn’t belong in the school because he would “never survive in this industry.”

Claude excelled above and beyond these hardships, graduating at #2 in his class and building a career in the hospitality business. He served for two years in the French Army as a butler to a general in Paris. Here he went on to work at some of the most renowned restaurants and hotels in Paris and London, such as Maxim’s and Hotel Mirabelle. In Paris he also met the owner of San Francisco’s acclaimed Ernie’s restaurant, who invited him to work there. He was promoted to General Manager at age 32, and oversaw the institution as it grew to be San Francisco’s most successful restaurant of its time. In 1981, he opened a Napa Valley restaurant which subsequently grew into a world-class luxury resort - aptly named Auberge Du Soleil, a fitting comeback to the instructor who told Claude he would never succeed in this industry. Claude’s last visit to his birthplace was in 1985, when he returned with his two daughters to see his mother’s grave. Claude found the Algeria of his childhood was unrecognizable: the street names were changed and beautiful landmarks had been destroyed. A road ran straight through the middle of the Jewish cemetery, which had become a “wilderness”, and it was impossible to find his mother’s burial plot. Miraculously, his daughter happened upon the very patch of land where his mother’s tombstone still stood. For Claude, the entire trip was worth this very moment.

Though Claude chose to leave North Africa, his family along with the rest of the Algerian Jewish population was forcibly expelled by 1962. Stripping of civil rights and violent pogroms made the country unlivable for Jews. Claude reflects with sorrow that Algeria has ceased to be home for a Jewish community, and cherishes his memories – “the one thing that nobody can take away from you.” His story is one of mourning but also of possibility and tremendous success, a true embodiment of the self-made man.

This film is part of the Testimonies produced by Sarah Levin for JIMENA's Oral History and Digital Experience. JIMENA - Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa - is a San Francisco, CA., based non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of culture and history of the Jews from Arab Lands and Iran, and aims to tell the public about the fate of Jewish refugees from the Middle East.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot, courtesy of JIMENA.

Mordechai Elul Recounts His Life in Oran, Algeria, and Jerusalem, Israel, 2018

(Video)Mordechai Elul was born in Oran, Algeria, in 1928. In this testimony he tells about his family and the Nazi occupation of Algeria. They immigrated to Israel in 1948 via Marseille, France, and traveled on the Pan York ship with 4,000 immigrants. It was a very difficult journey, and someone died on the way. They searched for a long time in Israel for the brother who came before them and almost gave up - until they met him. At first they lived in a transit camp (maabara) in Katamon, and from there they moved to Kiryat Yuval and the Katamon neighborhood in Jerusalem.

-------------------------

This testimony was produced as part of Seeing the Voices – the Israeli national project for the documentation of the heritage of Jews of Arab lands and Iran. The project was initiated by the Israeli Ministry for Social Equality, in cooperation with The Heritage Wing of the Israeli Ministry of Education, The Yad Ben Zvi Institute, and The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. The film was produced as part of the Seeing the Voices project, 2019

Dafna Poznansky Ben Hamo Recounts Her Life in Oran, Algeria, France, and Israel, 2018

(Video)Dafna Poznansky Ben Hamo was born as Catherine Joelle Ben Hamo in Oran, Algeria, in 1950, into a family who immigrated to Oran from Spanish Morocco. In this testimony she recounts her childhood in Oran, then the migration to France and the life in Marseille and in Nice and finally her immigration to Israel and her life in this country.

-------------------------

This testimony was produced as part of Seeing the Voices – the Israeli national project for the documentation of the heritage of Jews of Arab lands and Iran. The project was initiated by the Israeli Ministry for Social Equality, in cooperation with The Heritage Wing of the Israeli Ministry of Education, The Yad Ben Zvi Institute, and The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. The film was produced as part of the Seeing the Voices project, 2019

Jacques Guy Benhamou Recounts the Life of his Family in Algeria

(Video)Jacques Guy Benhamou of Échirolles, Isere (in suburban Grenoble), France, recounts the life of his family in Tlemcen and Oran, Algeria.

Jacques Guy Benhamou is the eldest of three sons born to an Algerian Jewish family. His Hebrew name is Yaakov, as it was traditional for the eldest son to carry his grandfather’s name. Jacques’s forebears lived in Debdou, Morocco, a small town on the road from Timbuktu to the Mediterranean. There were 12 large Jewish families in Debdou, and each family group had its own synagogue. The Benhamou family of Debdou made a living as peddlers supplying caravans. It was difficult for Jews in Debdou to make a living, and Guy’s great-grandfather and his family left for Algeria, when the French conquered the country in 1830.

Jacques’s father a stationmaster in Tlemcen, Algeria sadly passed away in 1938, leaving his mother with sons ages nine, six and three. After the death of his father, Jacques''s family moved in with their grandmother. Five Jewish families lived in his grandmother’s small property. His father’s death left his family poor, as women had no way to earn a living in those days. Young Jacques worked after school hand-copying documents for a notary.

Growing up, Jacques attended a French school, while Arab Muslim students attended separate schools. He went to Kabbalat Shabbat services every Friday night long after his Bar Mitzvah, and remembers that people attended mostly to hear the lovely melodies to which the prayers were chanted. There was no commentary on the Torah portion (parsha), and the tones for chanting the parsha had to be precise. On the whole, the Jewish community of Tlemcen was well-organized. Jacques, remembers with gratitude the efforts of the Jewish community leaders. They rebuilt the synagogue and renovated the Jewish pilgramge site of Rabbi Ephraim Enkaoua’s tomb. There was an association to help provide poor girls with what they needed for their weddings, as well as a charity which gave funds to poor community members so they could celebrate Jewish festivals.

Jacques fondly recalls the celebrations honoring Rabbi Ephraim Enkaoua, who journeyed from Toledo to Tlemcen after the 1392 pogrom, a century before the Spanish Expulsion. The hilula (anniversary of death) pilgrimage to the grave of Rabbi Ephraim Enkaoua at Lag B’Omer was the highlight of a full week of festivities. The peak of the hilula festival was a pilgrimage to Rabbi Enkaoua’s grave. People knelt and kissed the grave, pouring water on sugar so that their prayers would be sweet. Pilgrims were received in the big synagogue, speeches were delivered, candles were lit, and dances and concerts of Judeo-Arabic music filled the air. Many souvenirs were sold, and it was a popular week to hold weddings.

The French Vichy regime, a collaborator with Nazi Germany, imposed their anti-Jewish laws in Algeria in 1940. The lives and livelihoods of Algerian Jews were increasingly threatened. It began with restrictions placed on Jews, as they were banned from practicing certain professions. Students were made to learn German songs. Jacques recalls being “scared to death” during the dangerous sports he was forced to play at school such as walking on a wall. Eventually, Jacques – along with most Jewish children – was forced to stop attending school altogether. French citizenship was revoked for Jewish residents, property was confiscated and many of the young men in Jacques’s Jewish community were forced into the Bedeau Jewish Labor Camp.

American troops landed in North Africa in 1942, clearing the region of German and Italian forces. Jacques befriended two American soldiers when they arrived in Tlemcen. They picked him up in their Jeep and asked him to show them around. The soldiers needed their shirts laundered, so he took the shirts home to his mother. They were pleased with her work, and Mrs. Benhamou began generating enough income for her family’s survival by laundering and mending soldiers’ clothes. She was paid in both money and food, supplementing the family’s limited rations.

Years later, in 1958, after President Charles De Gaulle came to power some Algerian Jews held hope that conditions would improve, but unfortunately they did not. The Algerian War of Independence raged on and terrorist attacks by the National Liberation Front (FLN) continued to erupt, including a bombing at the home of Jacques’s neighbor, who was the Chief of Police. Jacques, who by this time had become a teacher, recalls describes the impending violence: “I even had to check my own pupils from the school where I taught to open their schoolbags. For a week we had to watch the huge gas storage tanks to make sure there were no terrorists. Once we stayed in a camp where terrorists were imprisoned. I spent 2 hours at night in a “mirador” guard tower, with lights to watch.”

As a result of the detiorating conditions in Algeria, Jacques requested to be relocated to a school in France and was placed in Grenoble, along with his fellow Algerian Jewish teachers. Jacques reflects on emigrating: “It was a relief to leave Algeria. Yellow stars were already on stock in the town halls.” While France was safer, the treatment of Algerian Jews was still harsh and discriminator. Apartment rental agencies would reject Jacques as soon as they learned his name. His first winter in the country, he was evicted – an action he only later learned was illegal in France. Jacques explains the importance of both aliyah to Israel, as well as maintaining a strong Jewish community within France. “I would advise young people to go to Israel. Older people need to stay as we need a strong, united Diaspora in France, to counterbalance France’s permanent anti-Semitic, anti-Zionist attitude.” Jacques reminds us the importance of preserving and passing on our history and heritage: “Everything I have done since I retired has been for my grandchildren, to remember who you come from and what we have gone through. Remember this history, to give you courage to go on! We must go on!

This film is part of the Testimonies produced by Sarah Levin for JIMENA's Oral History and Digital Experience. JIMENA - Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa - is a San Francisco, CA., based non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of culture and history of the Jews from Arab Lands and Iran, and aims to tell the public about the fate of Jewish refugees from the Middle East.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People, courtesy of JIMENA.

Roger Emile Haim Benichou Speaks About His Ancestry in Oran, Algeria, 2018

(Video)Roger Émile Haim Benichou was born in Oran, Algeria, in 1941. In these three video clips he talks about his ancestry: 1. An explanation about his name and those of his parents; 2. Family life in Oran; 3. Jewish life in Oran.

-------------------------

This testimony was produced as part of Seeing the Voices – the Israeli national project for the documentation of the heritage of Jews of Arab lands and Iran. The project was initiated by the Israeli Ministry for Social Equality, in cooperation with The Heritage Wing of the Israeli Ministry of Education, The Yad Ben Zvi Institute, and The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. The film was produced as part of the Seeing the Voices project, 2019

Passover seder at the Rouche family, Oran, Algeria, 1930

(Photos)Oran, Algeria, 1930

In the photo: The parents Yossef and Nedjma

Their children: Isaac, Maurice, Elie, Camille,

Leonie and Juliette

(The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot,

courtesy of Jacques Assouline, Israel)