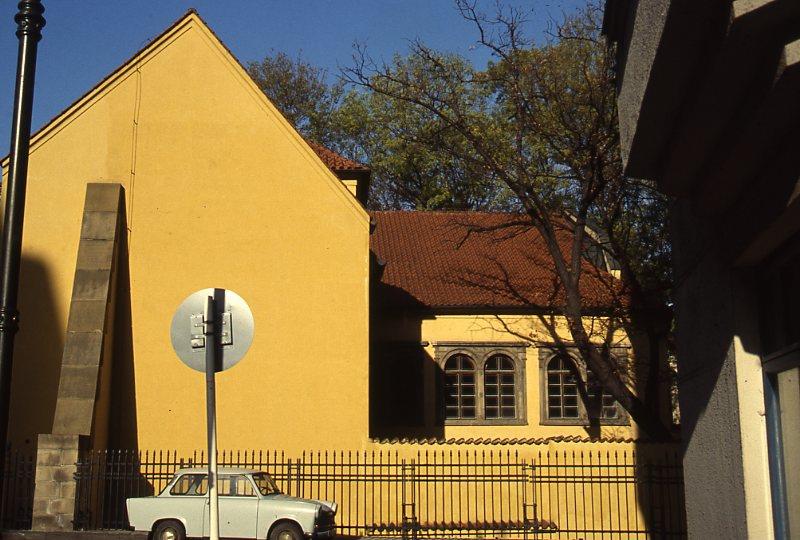

The Pinkas Synagogue (Pinkasova synagoga), external view, Prague, Czech Republic, 1992

Photo: Octav Moskuna

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People, Octav Moskuna collection

MOSKUNA

(Family Name)MOSKUNA, MOSKONA

Surnames derive from one of many different origins. Sometimes there may be more than one explanation for the same name. This family name is a patronymic surname derived from a male ancestor's personal name, in this case of biblical origin.

Moskuna is derived from Mosku / Moscu, a hypercoristic form of the given name Moshe common among the Ladino speaking Sephardi Jews of south eastern Europe. According to biblical etymology, the meaning of the name Moseh is "I drew him out of the water" (Exodus 2.10). The biblical Moses, who lived in the first half of the 13th century BCE, was the son of Amram and Jochebed of the tribe of Levi, and the brother of Aaron and Miriam.

A popular personal name, Moses developed numerous variants which became widespread as family names throughout the Jewish world. Bar Mosheh is recorded in the late 7th century in southern Morocco, Musa in 11th century Spain and Ben Mosheh in 11th century Italy. Moss and Mosse are found in the 12th century English pipe rolls (official financial records).

Ben Muca is documented in 1439, Muca in 1440, Ibn Mussa and Ben Mussa in the 15th century, and Mousha in the 19th century.

Distinguished bearers of the family name Moskuna include the Bulgarian-born Israeli actor and singer Arie Moskuna (b. 1947).

Prague

(Place)Capital of the Czech Republic. Formerly the capital of Czechoslovakia.

It has the oldest Jewish community in Bohemia and one of the oldest communities in Europe, for some time the largest and most revered. Jews may have arrived in Prague in late roman times, but the first document mentioning them is a report by Ibrahim Ibn Ya'qub from about 970. The first definite evidence for the existence of a Jewish community in Prague dates to 1091. Jews arrived in Prague from both the east and west around the same time. It is probably for this reason that two Jewish districts came into being there right at the beginning.

The relatively favorable conditions in which the Jews at first lived in Prague were disrupted at the time of the first crusade in 1096. The crusaders murdered many of the Jews in Prague, looted Jewish property, and forced many to accept baptism. During the siege of Prague castle in 1142, the oldest synagogue in Prague and the Jewish quarter below the castle were burned down and the Jews moved to the right bank of the river Moldau (vltava), which was to become the future Jewish quarter, and founded the "Altschul" ("old synagogue") there.

The importance of Jewish culture in Prague is evidenced by the works of the halakhists there in the 11th to 13th centuries. The most celebrated was Isaac B. Moses of Vienna (d. C. 1250) author of "Or Zaru'a". Since the Czech language was spoken by the Jews of Prague in the early middle ages, the halakhic writings of that period also contain annotations in Czech. From the 13th to 16th centuries the Jews of Prague increasingly spoke German. At the time of persecutions which began at the end of the 11th century, the Jews of Prague, together with all the other Jews of Europe, lost their status as free people. From the 13th century on, the Jews of Bohemia were considered servants of the royal chamber (servi camerae regis). Their residence in Prague was subject to the most humiliating conditions (the wearing of special dress, segregation in the ghetto, etc.). The only occupation that Jews were allowed to adopt was moneylending, since this was forbidden to Christians and considered dishonest. Socially the Jews were in an inferior position.

The community suffered from persecutions accompanied by bloodshed in the 13th and 14th centuries, particularly in 1298 and 1338. Charles IV (1346- 1378) protected the Jews, but after his death the worst attack occurred in 1389, when nearly all the Jews of Prague fell victims. The rabbi of Prague and noted kabbalist Avigdor Kara, who witnessed and survived the outbreak, described it in a selichah. Under Wenceslaus IV the Jews of Prague suffered heavy material losses following an order by the king in 1411 canceling all debts owed to Jews.

At the beginning of the 15th century the Jews of Prague found themselves at the center of the Hussite wars (1419- 1436). The Jews of Prague also suffered from mob violence (1422) in this period. The unstable conditions in Prague compelled many Jews to emigrate.

Following the legalization, at the end of the 15th century, of moneylending by non-Jews in Prague, the Jews of Prague lost the economic significance which they had held in the medieval city, and had to look for other occupations in commerce and crafts. The position of the Jews began to improve at the beginning of the 16th century, mainly owing to the assistance of the king and the nobility. The Jews found greater opportunities in trading commodities and monetary transactions with the nobility. As a consequence, their economic position improved. In 1522 there were about 600 Jews in Prague, but by 1541 they numbered about 1,200. At the same time the Jewish quarters were extended. At the end of the 15th century the Jews of Prague founded new communities.

Under pressure of the citizens, king Ferdinand I was compelled in 1541 to approve the expulsion of the Jews. The Jews had to leave Prague by 1543, but were allowed to return in 1545. In 1557 Ferdinand I once again, this time upon his own initiative, ordered the expulsion of the Jews from Prague. They had to leave the city by 1559. Only after the retirement of Ferdinand I from the government of Bohemia were the Jews allowed to return to Prague in 1562.

The favorable position of the Jewish community of Prague during the reign of Rudolf II is reflected also in the flourishing Jewish culture. Among illustrious rabbis who taught in Prague at that time were Judah Loew B. Bezalel (the "maharal"); Ephraim Solomon B. Aaron of Luntschitz; Isaiah B. Abraham ha-levi Horowitz, who taught in Prague from 1614 to 1621; and Yom Tov Lipmann Heller, who became chief rabbi in 1627 but was forced to leave in 1631. The chronicler and astronomer David Gans also lived there in this period. At the beginning of the 17th century about 6,000 Jews were living in Prague.

In 1648 the Jews of Prague distinguished themselves in the defense of the city against the invading swedes. In recognition of their acts of heroism the Emperor presented them with a special flag which is still preserved in the Altneuschul. Its design with a Swedish cap in the center of the Shield of David became the official emblem of the Prague Jewish community.

After the thirty years' war, government policy was influenced by the church counter-reformation, and measures were taken to limit the Jews' means of earning a livelihood. A number of anti-Semitic resolutions and decrees were promulgated. Only the eldest son of every family was allowed to marry and found a family, the others having to remain single or leave Bohemia.

In 1680, more than 3,000 Jews in Prague died of the plague. Shortly afterward, in 1689, the Jewish quarter burned down, and over 300 Jewish houses and 11 synagogues were destroyed. The authorities initiated and partially implemented a project to transfer all the surviving Jews to the village of Lieben (Liben) north of Prague. Great excitement was aroused in 1694 by the murder trial of the father of Simon Abeles, a 12-year-old boy, who, it was alleged, had desired to be baptized and had been killed by his father. Simon was buried in the Tyn (Thein) church, the greatest and most celebrated cathedral of the old town of Prague. Concurrently with the religious incitement against the Jews an economic struggle was waged against them.

The anti-Jewish official policy reached its climax after the accession to the throne of Maria Theresa (1740-1780), who in 1744 issued an order expelling the Jews from Bohemia and Moravia. Jews were banished but were subsequently allowed to return after they promised to pay high taxes. In the baroque period noted rabbis were Simon Spira; Elias Spira; David Oppenheim; and Ezekiel Landau, chief rabbi and rosh yeshivah (1755-93(.

The position of the Jews greatly improved under Joseph II (1780-1790), who issued the Toleranzpatent of 1782. The new policy in regard to the Jews aimed at gradual abolition of the limitations imposed upon them, so that they could become more useful to the state in a modernized economic system. At the same time, the new regulations were part of the systematic policy of germanization pursued by Joseph II. Jews were compelled to adopt family names and to establish schools for secular studies; they became subject to military service, and were required to cease using Hebrew and Yiddish in business transactions. Wealthy and enterprising Jews made good use of the advantages of Joseph's reforms. Jews who founded manufacturing enterprises were allowed to settle outside the Jewish quarter of Prague.

Subsequently the limitations imposed upon Jews were gradually removed. In 1841 the prohibition on Jews owning land was rescinded. In 1846 the Jewish tax was abolished. In 1848 Jews were granted equal rights, and by 1867 the process of legal emancipation had been completed. In 1852 the ghetto of Prague was abolished. Because of the unhygienic conditions in the former Jewish quarter the Prague municipality decided in 1896 to pull down the old quarter, with the exception of important historical sites. Thus the Altneuschul, the Pinkas and Klaus, Meisel and Hoch synagogues, and some other places of historical and artistic interest remained intact.

In 1848 the community of Prague, numbering over 10,000, was still one of the largest Jewish communities in Europe (Vienna then numbered only 4,000 Jews). In the following period of the emancipation and the post- emancipation era the Prague community increased considerably in numbers, but did not keep pace with the rapidly expanding new Jewish metropolitan centers in western, central, and Eastern Europe.

After emancipation had been achieved in 1867, emigration from Prague abroad ceased as a mass phenomenon; movement to Vienna, Germany, and Western Europe continued. Jews were now represented in industry, especially the textile, clothing, leather, shoe, and food industries, in wholesale and retail trade, and in increasing numbers in the professions and as white-collar employees. Some Jewish bankers, industrialists and merchants achieved considerable wealth. The majority of Jews in Prague belonged to the middle class, but there also remained a substantial number of poor Jews.

Emancipation brought in its wake a quiet process of secularization and assimilation. In the first decades of the 19th century Prague Jewry, which then still led its traditionalist orthodox way of life, had been disturbed by the activities of the followers of Jacob Frank. The situation changed in the second half of the century. The chief rabbinate was still occupied by outstanding scholars, like Solomon Judah Rapoport, the leader of the Haskalah movement; Markus Hirsch (1880-1889) helped to weaken the religious influence in the community. Many synagogues introduced modernized services, a shortened liturgy, the organ and mixed choir, but did not necessarily embrace the principles of the reform movement.

Jews availed themselves eagerly of the opportunities to give their children a higher secular education. Jews formed a considerable part of the German minority in Prague, and the majority adhered to liberal movements. David Kuh founded the "German liberal party of Bohemia and represented it in the Bohemian diet (1862-1873). Despite strong Germanizing factors, many Jews adhered to the Czech language, and in the last two decades of the 19th century a Czech assimilationist movement developed which gained support from the continuing influx of Jews from the rural areas. Through the influence of German nationalists from the Sudeten districts anti-Semitism developed within the German population and opposed Jewish assimilation. At the end of the 19th century Zionism struck roots among the Jews of Bohemia, especially in Prague.

Growing secularization and assimilation led to an increase of mixed marriages and abandonment of Judaism. At the time of the Czechoslovak republic, established in 1918, many more people registered their dissociation of affiliation to the Jewish faith without adopting another. The proportion of mixed marriages in Bohemia was one of the highest in Europe. The seven communities of Prague were federated in the union of Jewish religious communities of greater Prague and cooperated on many issues. They established joint institutions; among these the most important was the institute for social welfare, established in 1935. The "Afike Jehuda society for the Advancement of Jewish Studies" was founded in 1869. There were also the Jewish museum and "The Jewish historical society of Czechoslovakia". A five-grade elementary school was established with Czech as the language of instruction. The many philanthropic institutions and associations included the Jewish care for the sick, the center for social welfare, the aid committee for refugees, the aid committee for Jews from Carpatho- Russia, orphanages, hostels for apprentices, old-age homes, a home for abandoned children, free-meal associations, associations for children's vacation centers, and funds to aid students. Zionist organizations were also well represented. There were three B'nai B'rith lodges, women's organizations, youth movements, student clubs, sports organizations, and a community center. Four Jewish weeklies were published in Prague (three Zionist; one Czech- assimilationist), and several monthlies and quarterlies. Most Jewish organizations in Czechoslovakia had their headquarters in Prague.

Jews first became politically active, and some of them prominent, within the German orbit. David Kuh and the president of the Jewish community, Arnold Rosenbacher, were among the leaders of the German Liberal party in the 19th century. Bruno Kafka and Ludwig Spiegel represented its successor in the Czechoslovak republic, the German Democratic Party, in the chamber of deputies and the senate respectively. Emil Strauss represented that party in the 1930s on the Prague Municipal Council and in the Bohemian diet. From the end of the 19th century an increasing number of Jews joined Czech parties, especially T. G. Masaryk's realists and the social democratic party. Among the latter Alfred Meissner, Lev Winter, and Robert Klein rose to prominence, the first two as ministers of justice and social welfare respectively.

Zionists, though a minority, soon became the most active element among the Jews of Prague. "Barissia" - Jewish Academic Corporation, was founded in Prague in 1903, it was one of the leading academic organizations for the advancement of Zionism in Bohemia. Before World War I the students' organization "Bar Kochba", under the leadership of Samuel Hugo Bergman, became one of the centers of cultural Zionism. The Prague Zionist Arthur Mahler was elected to the Austrian parliament in 1907, though as representative of an electoral district in Galicia. Under the leadership of Ludvik Singer the "Jewish National Council" was formed in 1918. Singer was elected in 1929 to the Czechoslovak parliament, and was succeeded after his death in 1931 by Angelo Goldstein. Singer, Goldstein, Frantisek Friedmann, and Jacob Reiss represented the Zionists on the Prague municipal council also. Some important Zionist conferences took place in Prague, among them the founding conference of hitachadut in 1920, and the

18th Zionist congress in 1933.

The group of Prague German-Jewish authors which emerged in the 1880s, known as the "Prague Circle" ('der Prager Kreis'), achieved international recognition and included Franz Kafka, Max Brod, Franz Werfel, Oskar Baum, Ludwig Winder, Leo Perutz, Egon Erwin Kisch, Otto Klepetar, and Willy Haas.

During the Holocaust period, the measures e.g., deprivation of property rights, prohibition against religious, cultural, or any other form of public activity, expulsion from the professions and from schools, a ban on the use of public transportation and the telephone, affected Prague Jews much more than those still living in the provinces. Jewish organizations provided social welfare and clandestinely continued the education of the youth and the training in languages and new vocations in preparation for emigration. The Palestine office in Prague, directed by Jacob Edelstein, enabled about 19,000 Jews to emigrate legally or otherwise until the end of 1939.

In March 1940, the Prague zentralstelle extended the area of its jurisdiction to include all of Bohemia and Moravia. In an attempt to obviate the deportation of the Jews to "the east", Jewish leaders, headed by Jacob Edelstein, proposed to the zentralstelle the establishment of a self- administered concentrated Jewish communal body; the Nazis eventually exploited this proposal in the establishment of a ghetto at Theresienstadt (Terezin). The Prague Jewish community was forced to provide the Nazis with lists of candidates for deportation and to ensure that they showed up at the assembly point and boarded deportation trains. In the period from October 6, 1941, to March 16, 1945, 46,067 Jews were deported from Prague to "the east" or to Theresienstadt. Two leading officials of the Jewish community, H. Bonn and Emil Kafka were dispatched to Mauthausen concentration camp and put to death after trying to slow down the pace of the deportations. The Nazis set up a treuhandstelle ("trustee Office") over evacuated Jewish apartments, furnishings, and possessions. This office sold these goods and forwarded the proceeds to the German winterhilfe ("winter aid"). The treuhandstelle ran as many as 54 warehouses, including 11 synagogues (as a result, none of the synagogues was destroyed). The zentralstelle brought Jewish religious articles from 153 Jewish communities to Prague on a proposal by Jewish scholars. This collection, including 5,400 religious objects, 24,500 prayer books, and 6,070 items of historical value the Nazis intended to utilize for a "central museum of the defunct Jewish race". Jewish historians engaged in the creation of the museum were deported to extermination camps just before the end of the war. Thus the Jewish museum had acquired at the end of the war one of the richest collections of Judaica in the world.

Prague had a Jewish population of 10,338 in 1946, of whom 1,396 Jews had not been deported (mostly of mixed Jewish and Christian parentage); 227 Jews had gone underground; 4,986 returned from prisons, concentration camps, or Theresienstadt; 883 returned from Czechoslovak army units abroad; 613 were Czechoslovak Jewish emigres who returned; and 2,233 were Jews from Ruthenia (Carpatho-Ukraine), which had been ceded to the U.S.S.R. who decided to move to Czechoslovakia. The communist takeover of 1948 put an end to any attempt to revive the Jewish community and marked the beginning of a period of stagnation. By 1950 about half of the Jewish population had gone to Israel or immigrated to other countries. The Slansky trials and the officially promoted anti-Semitism had a destructive effect upon Jewish life. Nazi racism of the previous era was replaced by political and social discrimination. Most of the Jews of Prague were branded as "class enemies of the working people". During this

Period (1951-1964) there was no possibility of Jewish emigration from the country. The assets belonging to the Jewish community had to be relinquished to the state. The charitable organizations were disbanded, and the budget of the community, provided by the state, was drastically reduced. The general anti-religious policy of the regime resulted in the cessation, for all practical purposes, of such Jewish religious activities as bar-mitzvah religious instruction and wedding ceremonies. In 1964 only two cantors and two ritual slaughterers were left. The liberalization of the regime during 1965-1968 held out new hope for a renewal of Jewish life in Prague.

At the end of March 1967 the president of "The World Jewish Congress", Nahum Goldmann, was able to visit Prague and give a lecture in the Jewish town hall. Among the Jewish youth many tended to identify with Judaism. Following the soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 there was an attempt to put an end to this trend, however the Jewish youth, organized since 1965, carried on with their Jewish cultural activities until 1972. In the late 6os the Jewish population of Prague numbered about 2,000.

On the walls of the Pinkas synagogue, which is part of the central Jewish museum in Prague, are engraved the names of 77,297 Jews from Bohemia and Moravia who were murdered by the Nazis in 1939-1945.

In 1997 some 6,000 Jews were living in the Czech Republic, most of them in Prague. The majority of the Jews of Prague were indeed elderly, but the Jewish community's strengthened in 1990's by many Jews, mainly American, who had come to work in the republic, settled in Prague, and joined the community.

In April 2000 the central square of Prague was named Franz Kafka square. This was done thanks to the unflinching efforts and after years of straggle with the authorities, of Professor Eduard Goldstucker, a Jew born in Prague, the initiator of the idea.

Czech Republic

(Place)Czech Republic

Also known as: Czechia, Česko

Česká republika

A country in Central Europe, member of the European Union (EU). The Czech Republic includes the historical territories of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia.

21st Century

Estimated Jewish Population in 2018: 3,900 out of 10,500,000 (0.03%). Main umbrella organization of Jewish communities:

Federation of Jewish Communities in Czech Republic

Phone: 420/224 800 824

Fax: 420/224 810 912

Email: sekretariat@fzo.cz

Web: www.fzo.cz

HISTORY

Jews of the Czech Lands

1454 | From Prosperity to Expulsion

Long before famous Israeli singer Arik Einstein crooned about “A Dream of Prague”, and before Judah Loew ben Bezalel, (1512/26 – 1609), known also by the Hebrew acronym of Maharal or The Maharal of Prague, supposedly created his famous Golem there, Moravia and Bohemia (now part of The Czech Republic) were home to a flourishing, prosperous Jewish community.

Various historical sources, including customs invoices and the testimony of Jewish traveler Abraham ben Yaacov – who was an envoy for the Caliph of Cordoba – document Jewish presence in Moravia and Bohemia as early as the 10th century. Works by medieval Jewish scholars – for instance, Arugat Ha-Bosem (“Spice Garden”) by Abraham ben Azriel of Bohemia, who lived in Prague, and Or Zaru'a by Isaac ben Moses of Vienna, a native of Bohemia – show that not only did Jews live in Czech territories, they also spoke and wrote in Czech. Concurrently, the Jews of Bohemia and Moravia enjoyed community autonomy in all matters regarding education, internal community arrangements, civil courts and so on.

In the mid-14th century, the area was home to the flourishing Hussite movement, headed by the Czech priest Jan Hus, who challenged the Catholic Church's religious hegemony and viewed the Bible and its heroes as the sole sources of authority. Many Jews believed that the Hussites were sent by God in order to vanquish the heretic Catholics and increase faith in the Jewish Torah. This belief was their undoing: they were accused of supporting the Hussites in the latter's war against The Catholic Church and Emperor, and were therefore expelled from five crown cities in Moravia. This happened in 1454, and those cities remained off-limits for Jews until the mid-19th century.

1552 | The Gershom Saga

The King of Bohemia, Emperor Rudolph II of the House of Habsburg (1552-1612) was considered an odd duck. This ruler, who suffered most of his life from severe depression, had some strange hobbies, which included the collecting of short people for amusement purposes and the establishment of a special regiment of giants in his army.

However, Rudolph II also enacted enlightened and progressive policies for the times, which were also highly beneficial to his Jewish subjects. During his reign the number of Jews in Prague doubled, and it became one of the global centers of Judaism. In this open and tolerant atmosphere and fruitful ties were forged between Jewish scholars and gentile scientists and clerics. The doors of the Czech economy also opened to the Jews, many of whom, like court Jews Mordechai Meisel ben Samuel and Jacob Bassevi von Treunberg, accumulated large fortunes.

During this time the Jewish printing presses also flourished, publishing books famous for their beautiful typography and unique illustrations. The best known of these was the Prague Haggada, printed at the press owned by Gershom ben Solomon Kohen. The books issued by Gershom Kohen's press included Jewish motifs alongside Royal Habsburg emblems. The trademark of the press was the skyline of Prague set between two lion's tails, inspired by the official emblem of the Kingdom of Bohemia. The Kohen family – and after it the Bak family, which continued the Prague printing tradition – mostly produced rabbinic literature, prayer books and morality pamphlets in Hebrew and Yiddish.

1609 | The Maharal of Prague

One of the giants of Jewish thought throughout the ages was Judah Loew ben Bezalel better known as “The Maharal of Prague” (1512/26-1609). The Maharal wrote dozens of books and treatises, which testify to his sharp mind, phenomenal memory, deep understanding of human nature and extraordinary command of Jewish scriptures, as well as the secular science and learning of his time. Like Maimonides, the Maharal was greatly influenced by Aristotle and often used philosophical and allegorical interpretations for the writings of the sages, whom he viewed as the sole authority to understanding the wisdom of God. His greatness is all the more impressive in light of the fact that he was self-taught, acquiring all his knowledge on his own, with no formal education.

The Maharal never served in any official capacity, but functioned as the de-facto head of the Jewish community of Prague. In this role the Maharal became famous for his great social sensibilities, often criticizing the rich men of the community for their alienation from the lower classes. The Maharal also had a well-grounded educational world-view, believed in freedom of expression and was often critical of the pilpul, the subtle legal, conceptual, and casuistic differentiation method of studying the Talmud prevalent in the yeshivas, which he felt focused on the marginal rather than the salient.

One of the most famous legends concerning him was that of the Golem of Prague: An artificial creature made of clay, which the Maharal supposedly invested with the breath of life to protect the Jews from blood libels and persecution. The Golem ignited the imagination of many an author and is considered today as one of the founding myths of mysticism and of the science fiction genre.

1648 | Windows 18

Throwing people out of windows was a common practice in Czech politics for declaring a revolution.

In 1618 the King of Bohemia, Ferdinand II, sent Catholic envoys on his behalf to Prague, to prepare the ground for his arrival. The people of the city threw the envoys from the window of Hradcany (Prague Castle), an event that became known to history as “The Defenestration of Prague.”

This act of violence was the start of the Thirty Year War between Catholics and Protestants throughout Europe. The war ended in 1648, with the Peace of Westphalia. The Jews, who maintained neutrality during the war and probably, in the spirit of Menachem Begin's famous quip about the Iran-Iraq war, “wished both sides success”, flourished during the fighting. In 1627, the Emperor Ferdinand II expanded their rights, and according to a 1638 census, the number of Jews in the Kingdom of Bohemia reached 7,815.

In 1650, after the end of the war, the Emperor Ferdinand III issued an order of expulsion for Jews who did not live in the kingdom prior to the war. Charles IV followed him with the “Families Law”, which limited Jewish settlement in Bohemia and allowed for only one family member to marry. But they were both outdone by the Empress Maria Theresa, who expelled the Jews of Prague with the edict of 1744, which was rescinded four years later. Due to their experience of frequent edicts and persecutions, the Jews spread out through the rural Czech areas. Official documents show that in 1724 Jews resided in some 800 different locations throughout Bohemia and Moravia.

1781 | The Right of Association

In the second half of the 18th century Czech Jews began to integrate into society at large. One of the expressions of this development was the establishment of Jewish artisan guilds. The Jewish merchants copied the model of the Christian guilds, formed a series of rules regulating the trade amongst themselves and even had a flag and emblems to represent them at the various fairs. An official document from 1729 shows 2,300 Jewish artisans organized in professional guilds in Prague, including 158 tailors, 100 cobblers, 39 milliners, 20 goldsmiths, 37 butchers, 28 barbers and 15 musicians.

In 1781 Emperor Joseph II issued the “Tolerance Edict,” in the spirit of the enlightened absolutism then in vogue, which held the best interests of the state above all else and was based on the values of the Enlightenment, particularly on rationalism and a separation of church and state. The edict, which declared the Jews to be “Useful subjects of the Crown,” was met with mixed feelings by the Jews themselves. While it gave them freedom of occupation, encouraged them to enter public life and allowed them to study at institutions of higher learning, it also forced them to de-emphasize their Jewish identity, study at secular schools, adopt non-Jewish last names and decrease their use of Hebrew and Yiddish.

1848 | To the New World

In 1848 there were some 10,000 Jews living in Prague, mostly in the Jewish Quarter. These were the tense days following the defeat of the “Spring of Nations” revolution, and pogroms were a frequent occurrence. The homes and businesses of many Jews were targeted for looting, and they themselves were beaten and humiliated on a daily basis.

Many of the leaders of the Jewish communities in the region called upon their parishioners to emigrate to the New World beyond the sea: The United States of America. Among the most prominent Jewish immigrants to the United States was Isidore Bush, a businessman, columnist, freedom fighter and senior officer in the American Civil War, and Adolph Brandeis – father of Louis Brandeis, future US Supreme Court Justice and an avid supporter of the Zionist movement.

In 1861 Czech Jews were granted the right to own land. Many of them began to specialize in various agricultural fields, mostly the production of sugar and the wholesale trade of seeds. Many Jews were also prosperous business owners in the cotton and beer trades, in the exporting of eyeglasses and in the coalmines of Moravska-Ostrava. Six years later Czech Jews became members of the exclusive club, alongside countries such as Prussia, which granted the Jews full emancipation.

1898 | Emotions vs. Intellect

When the revered Czech leader Tomas (Thomas) Masaryk was asked when he completely overcame antisemitism, he replied: “Good God, emotionally perhaps never. Only intellectually”. His honest answer clearly reflects the power with which the anti-Semitic idea had taken root in Europe by the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

A few years earlier, in 1898, Masaryk successfully endured the ancient battle between emotion and intellect when he stood by a young Jewish man named Leopold Hilsner, who was accused of cutting the throat of a young Czech woman near the town of Polna and using her blood to bake matza. Despite Masaryk's advocacy, Hilsner did not receive a new trial and languished in prison until 1916, when he was released as part of a mass clemency announced by Charles I, the last ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Against the backdrop of such antisemitism the echoes of the Zionist idea reached the Czech lands, mostly through Jewish students from Moravia who studied in Vienna, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, of which the Czech lands were then a part. These young men and women were deeply influenced by the writings of Theodore Herzl, and in time some of them became important leaders of the Jewish people. Shmuel Hugo Bergman, Hans Kohn and Max Brod, for instance, were avid member of the Kochba Zionist movement in the Czech lands, which upheld the ideal of Jewish resistance inspired by Max Nordau's “Muscular Judaism.”

1918 | Peace between Wars

The Czech regions of Moravia and Bohemia was home to two ethnic groups – Czechs and Germans. While most of the population was Czech, the cultural elite was influenced by Germany, the giant neighbor.

Czech Jews were no exception. The most prominent among them were writers such as Friedrich Adler, Franz Kafka, Franz Werfel and Ludwig Winder, who wrote in German and were steeped in German culture. Alongside them worked Jewish writers from rural areas, including Hanus Bon, Jiri Weil and Frantisek Langer, whose works romanticized country life.

Following the WW1, a new state was formed in the region by the name of Czechoslovakia, which included four historic territories: Bohemia, Moravia, Slovakia, and Ruthenia to the east. Czechoslovakia between the two world wars was a model of Western democracy. Its authorities recognized all the rights of the Jewish minority living within its borders, which numbered about 356,000 people, who enjoyed equal rights and a period of great prosperity.

Despite constituting only about 2.5% of the population, the Jews held prominent positions in the economy, industry and culture of Czechoslovakia. Some 18% of all students were Jews, and members of the Jewish community stood out in the fields of journalism, politics and public life as well. What's more, the authorities legitimized the Jewish national movement and had many dealings with the Zionist movement.

1924 | A Deathbed Wish Denied

The great writer Franz Kafka was born to a middle-class Jewish family in Prague. His father was a well-to-do haberdashery merchant and his mother was an educated woman, from a Levi family. Kafka, who lived most of his life in Prague, passed away in 1924 at the young age of 41.

Before he expired, as he lay dying of tuberculosis, he asked his close friend Max Brod to burn all his manuscripts once he was gone. Happily for the entire world, Brod did not keep this promise, and dedicated all his time after Kafka's death to printing and spreading his close friend's works. Masterpieces such as “Metamorphosis”, “The Trial” and “The Castle” have become mainstays of Western literature, and Kafka's very name has become synonymous with modern man, lost in the maze of unfeeling institutions closing in on him.

Kafka wrote in German, spoke in Czech and even learned a little Hebrew. In his stories he composed a harsh indictment of the very notion of establishment, with the malice and stupidity inherent in it, but at the same time managed, in the spirit of Freudian psychology which began to gain currency in those days, to subtly plumb the depths of the soul of modern man in a world crumbling into barbarism – as the years that followed his death proved, with the outbreak of WW2.

1939 | The Proverbial Black Umbrella

The day after September 29th,1938, the day the Munich Accords were signed, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain stood at Heston Aerodrome in London, proudly waving the “peace” agreement he had signed with Hitler. While Chamberlain held the famous black umbrella, which has since become a symbol of appeasement and surrender, the Nazi army invaded the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia – an event that augured the outbreak of the WW2 less than a year later, on September 1st 1939.

A few months after the annexation of the Sudetenland region Germany declared Bohemia and Moravia to be a German “protectorate”. As a first step, all Jews were expelled from Bohemia and Moravia and their belongings were confiscated. By October 1941 some 27 thousand Jews left the Czech lands, becoming refugees throughout the rest of the country. The second phase began on November 24th, when 122 trains left the protectorate carrying 73,608 Jews to Theresienstadt Ghetto (see below) and from there to the gas chambers. Some 263,000 Jews of Czechoslovakia were murdered during the war, of them 71,000 from Bohemia and Moravia.

1944 | A Model Ghetto

On July 23rd, 1944, a Red Cross delegation entered Theresienstadt Ghetto in order to check whether the rumors of the concentration camps established by the Nazis in order to annihilate the Jews of Europe were true. The Nazis, who knew of the delegation's arrival ahead of time, staged an event portraying themselves as a model of enlightenment and humanitarianism: They filled the ghetto with fake cafes, model schools, playgrounds and vegetable gardens, and even produced a propaganda film painting the ghetto as a pastoral country resort. As soon as the production ended most of the “actors”, including many children, were sent to the gas chambers of Auschwitz. In time Theresienstadt Ghetto came to symbolize the full horror of the Holocaust, because of the monstrous pretense created by the Nazis there to delude the enlightened world. Theresienstadt, “the upscale ghetto”, where many famous writers, artists and rabbis were imprisoned, was built in Terezin, north of Prague. The ghetto served as a concentration camp for the Jews of Moravia and Bohemia and for elderly Jews of fame and special privileges, en route to transfer to the death camps.

Management of the ghetto was entrusted to a Council of Elders which was responsible for organizing the labor, distributing food, sanitation and cultural affairs, and internal jurisdiction. Lectures and seminars were held and a library holding 60,000 books was established!

Due to the many artists, writers and scholars living in the ghetto, a robust cultural life developed there. Orchestras, an opera troupe, a theater company and entertainment and satire revues were held. An amusing satirical example describes the ghetto menu thus: “Grilled yawn, stuffed breast of mosquito, leg of flea, frog knee a-la gypsum”.

According to historical sources, between 1941-1945 some 140,000 Jews were forcibly sent to Theresienstadt. By the end of the war, only 19,000 of them survived.

2000 | A Spiritual Monument

After WW2 some 45,000 Jews lived in Czechoslovakia, mainly in Moravia and Bohemia. Upon the rise of the Communist regime in the country, the Jewish community was cut off from its counterparts around the world, but early in this period, between 1948-1950, some 26,000 Jews emigrated from Czechoslovakia, of which 19,000 came to the newly established State of Israel. In the early 2,000s the Jewish community of the Czech Republic numbered approximately 1,700 people.

In 1991 Czechoslovakia split into two countries: The Czech Republic and Slovakia. The Jewish Czech community holds educational activities, and operates a kindergarten and the Gur-Ariyeh School – so named after the Maharal's famous book. In addition, the community operates synagogues and retirement homes, holds Torah classes and cultural activities and provides religious and welfare services. The cultural heritage of the Czech Jews is on display at the famous Jewish Museum in Prague.

The story of this museum is an unusual one: During WW2 the Nazis wished to preserve a future site as the “Exotic Museum of the extinct race”, meant to preserve the heritage of the people they meant to annihilate upon completion of the “Final Solution”. The Nazis believed that the museum would serve to aid anti-Semitic propaganda and justify their actions. Jewish artifacts were collected and looted with typical German efficiency from 153 communities, and the museum's inventory included some 100,000 works of art. The museum staff – who mostly perished in the Holocaust – quickly and feverishly documented the lives of Jewish communities in the Czech lands. The cultural treasure left behind by these people and their devoted work, with the thug's sword against their throats, are a testimony to their power and dedication, and a spiritual monument to their memory.