The Jewish Community of Recife

Recife

A city in northeastern Brazil, capital of the state of Pernambuco, fourth-largest urban agglomeration in Brazil.

When Recife became a prosperous center for sugar production in the 16th and 17th centuries, Portuguese settlers of Jewish descent and New Christians or crypto-Jews were already living in the town and its environs. They gave impetus to sugar production and commerce. The large number of New Christians in Recife (including the first historian of Brazilian economic life, Ambrosio Brondao), took part in a variety of activities, and bound themselves through intermarriage to prestigious old Christian families.

Denunciations on the part of inquisitional officers and of "Friends of the Holy Office" acquainted the inquisitors with a great number of Portuguese - for the most part new Christians - who did not conform to the fixed patterns of behavior imposed by the Church. Thus the new Christian Diego Fernandez, the greatest expert in sugar plantations, was accused by the Inquisition of being a "judaizer." the Inquisition dispatched an official inspector (visitator) for the purpose of seizing and confiscating the suspects' possessions, and an inquisitional commission was established in 1593 in Olinda, the port of Recife. New Christians were tried and arrested; some were taken to Lisbon and handed over to the inquisitional tribunal. After the inspector had left, surveillance of New Christians was continued by the bishop of Brazil, with the assistance of the local clergy and Jesuits. In 1630 Pernambuco was occupied by the Dutch, and it remained in their hands until 1654. This was an important period in Jewish history in Latin America, as Brazil was the only region - during colonial times - where Jews were permitted to practice their religion openly and establish an organized community.

Its members were mainly Jews from Holland, joined by new Christians already living in the colony. The Jews of Recife were known as financiers, brokers, sugar exporters, and suppliers of negro slaves. Their congregation, Tzur Israel, maintained a synagogue, the religious schools Talmud Torah and Etz Chayim, and a cemetery. In 1642 the first rabbi of the New World, Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, arrived from Holland, accompanied by the Chakham Moses Rafael de Aguilar and a large number of immigrants. The synagogue's cantor was Josue Velosino, and notables included David Senior Coronel, Abraham de Mercado, Jacob Mocatta, and Isaac Castanho. According to the minute books of the congregation, there were approximately 1,450 Jews in Dutch brazil in 1645; the number diminished to 720 in 1648 and to 650 in 1654. The majority lived in Recife and its environs. Despite official tolerance, however, the Jews were victims of hostility and discrimination at the hands of Calvinists and Catholics. With the

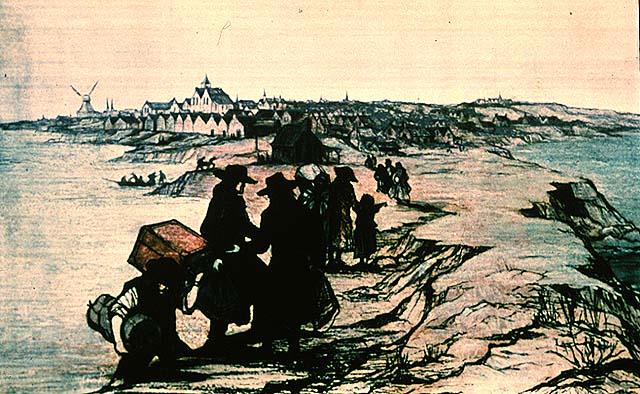

start of the Reconquest, the Jews were victimized by both the Dutch and the Portuguese, and in 1645 various Jewish prisoners were executed as allies of the Dutch; others were sent to Lisbon and handed over to the Inquisition; still others returned to Holland. After several years of fighting, the Portuguese succeeded in reconquering the territory thanks to the creation of the Commercial Company for Brazil (in Lisbon), most of whose capital came from New Christians. After the fall of Recife, the Jewish community disintegrated, and those who had openly professed their Judaism left Brazil together with the Dutch. These emigrants developed the sugar industry of the Antilles. After many difficulties, 23 of these Jewish emigrants arrived in New Amsterdam, where they founded the first Jewish community of what later became the town of New York.

New Christians continued to live in Recife, some as crypto-Jews. Two decades after the departure of the Dutch, the Inquisition was also acquainted with and persecuted the New Christians who had converted to Judaism during the Dutch occupation and had remained in Pernambuco. Many reports reached the Lisbon Inquisition in the second half of the 17th century and during the 18th century regarding their clandestine observance of Jewish rituals. Portuguese policy in the middle of the 18th century eventually enabled the New Christians to mingle with the rest of the population, until their traces disappeared as they became completely assimilated.

The present-day Jewish community in Recife was founded by immigrants from Eastern Europe, particularly Russia, Romania, and Poland, who settled there in the second decade of the 20th century. They number 350 families (1,600 persons) and maintain a Centro israelita, a high school (colegio), whose 350 pupils constitute 90% of all Jewish pupils attending schools, a synagogue, and various Jewish organizations.

In 1997 there was an active Jewish community in Recife. Brazil’s Jewish population then was 130,000, most of them lived in the two largest cities, Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

Jacob Hazan (center), wife Berta and friends, Recife, Brazil, 1954

(Photos)(The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot,

courtesy of Sara Gandelmann, Israel)

Isaac Aboab da Fonseca

(Personality)Isaac Aboab da Fonseca (also known as São João de Luz) (1605-1693), rabbi, as rabbi of Recife in Brazil, he is the first rabbi known to have served a Jewish community in the Americas, born in Castro Daire (Castro d'Ayre), Portugal, into a crypto-Jewish family. Following the increasing pressure of the Inquisition, Aboab was brought to Amsterdam as a child, when his family like many other crypto-Jewish families left Portugal. In Amsterdam, even as a young teenager, he gained recognition as an exceptional rabbi, gifted orator, respected teacher, and skilled translator of Kabalistic texts from Hebrew and Spanish. Already at the age of 21, he was appointed as the leader of one of Amsterdam's three congregations. In 1642, Aboab moved to Brazil to oversee the burgeoning Jewish community that was established in Recife, at the time part of the Dutch possessions in South America, thus becoming the first Jewish religious leader in all of America. During this time, he also authored a number of texts, apparently the first works written in Hebrew in America. From 1642 to 1654, he served as the rabbi of the Jewish community in Recife, actively participating in the defense of the city, which had long been under siege by the Portuguese. When Recife was recaptured, the Dutch stipulated in the terms of surrender that the lives of the Jews be spared. Some of them went on to establish the community of New Amsterdam (later known as New York), while others, including Isaac Aboab, returned to the Netherlands.

Upon his return to Amsterdam, Aboab assumed leadership of a yeshiva and became a member of the rabbinical tribunal. He played a significant role in representing the kabbalist tradition of Isaac Luria in Amsterdam. He translated from Hebrew into Spanish the works of the philosopher and kabbalist Abraham Cohen de Herrera (c.1570-c.1635).

Aboab served as the head of the Sephardic community during the inauguration of the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam in 1672. Additionally, he was one of the signatories of the edict of the herem (ban) against Baruch Spinoza in 1656.

Isaac Nahon

(Personality)Isaac Nahon (1907-2000), general of the Brazilian army, born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, into a family of Jewish immigrants from Oran, Algeria. He entered the military service in 1918 and studied at Realengo Military School in Rio de Janeiro graduating in 1925. As an artillery officer he rose through the ranks from lieutenant in 1928 to colonel in 1952. After serving in several positions within the Brazilian army, he was named military attache at the Brazilian embassy in Paraguay holding that position from 1959 to 1961. After graduating from the Higher Military School of War in 1962, he was advanced to the rank of brigadier general. As commander of the IV Army based in Recife, during the 1964 military coup Nahon was responsible for the arrest of Pelopidas Silveira, the mayor of Pernambuco, who was elected with the support of the left parties. His next position was chief of staff of the III Army, based in Porto Alegre, and after having been advanced to the rank of division general in 1965, he became commander of the eight-military region based in Belem. As of 1969 he served commander of the Main Directorate of Army Personnel with the rank of full general.

Julien Mandel

(Personality)Julien Mandel (born Julien Mandelbaum) (1893-1961), photographer, best known for his portraits and photographs of female nudes, born in Chelm, Poland. He showed a passion for drawing from a young age and received a Kodak camera as a gift at six. After serving in the the Russian Army during WW I, he worked in St. Petersburg and Moscow, Russia, and then in Vienna, Belgrade, and Rome before settling in Paris in 1919, where he opened a studio and worked as a retouching photographer. In 1926, he gained the right to reside in France and opened a studio on the prestigious Champs-Élysées, where he photographed French elites, including politicians, under the pseudonym Julien Mandel. His work was also featured in newspapers, advertisements, and erotic postcards, which depicted models in both studio and outdoor settings. Mandel went bankrupt in 1932 and left France in 1935 for Brazil, where he reopened a photo studio and also worked as a documentary filmmaker and film producer until his death in Recife in 1961.

Guadeloupe

(Place)Guadeloupe

A group of islands in the Caribbean forming an overseas region of France.

21st Century

Main Jewish organization:

Communauté Culturelle Israélite de la Guadeloupe (C.C.I.G.)

1 Bas du Fort

97190 Gosier

Pointe-a-Pitre

Guadeloupe

Phone 05 90 90 99 08

E-mail: ccig.orsameah@gmail.com

HISTORY

Guadeloupe was colonized by the French. Jews arrived in Guadeloupe during the 17th century, mainly from north-eastern regions of Brazil, after that area was recaptured by the Portuguese from the Dutch and the reintroduction of the Inquisition. The first synagogue in Guadeloupe was established in 1676 serving a Jewish population estimated at about 800. However, new legislation introduced in 1685, the "Black Code" of Louis XIV, prohibited the settlement of Jews in French colonies. Although some Jews visited or traded in Guadeloupe, particularly after the 18th century when a few Jews from Bordeaux, France, were allowed to settle in the neighboring Martinique, no significant Jewish presence was established until the 1950s.

The community was officially formed in February 1980, when the first synagogue was built. The synagogue Or Sameah was opened in June 1988 along with a community center, Talmud Torah, kosher store, and cemetery. The communal life flourished in the early 21st century. n June 1988, inauguration of the current synagogue and the community center.

Most members of the community are from North Africa and the services are celebrated according to the Sephardic rite. There about 120 Jewish families living in Guadeloupe. The community is member of the Consistoire Central de France.

Brazil

(Place)Brazil

República Federativa do Brasil - Federative Republic of Brazil

The largest country in both South America and Latin America.

According to the census conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) in 2010, there were 107,329 Jews living in Brazil, making it home to the second largest Jewish community in Latin America (after Argentina) and the 11th largest in the world. In addition to the over 100,000 acknowledged Jews, it is likely that there are others in Brazil with Jewish ancestors, though the precise numbers are unknown. According to research conducted in 1999 by the sociologist Simon Schwartzman, 0.2% of Brazilian respondents said they had Jewish ancestry, a percentage that in a population of about 200 million Brazilians, would represent about 400,000 people.

Jewish history in Brazil can be broken down into four distinct periods:

1) The arrival of New Christians and the Inquisition. This took place during the period when Brazil was a colony of Portugal (1500-1822);

2) The formation of a Jewish community during the 17th century in Recife, the capital of the state of Pernambuco in northeastern Brazil. This occurred during the invasion period and Dutch rule, when Jews were granted religious freedom;

3) The modern period (1822-1889), when there began to be wider acceptance of different religions, prompting immigration from a number of European and Arab countries (as well as from Japan). The first Jewish community in the modern period was formed in Belem (Bethlehem), in the state of Para; later, another community was formed in Rio de Janeiro. At the end of this period, in 1889, Brazil adopted a constitution that guaranteed religious freedom;

4) The contemporary period, when communities formed in agricultural colonies in Rio Grande do Sul during the first decade of the 20th century, and communities were established in some of the main cities in Brazil after the First World War.

THE COLONIAL PERIOD (1500-1822)

Thousands of Portuguese New Christians came to Brazil during the colonial period but did not establish organized Jewish communities. Indeed, with the exception of when Brazil was under Dutch rule, until Brazil proclaimed its independence in 1822, Catholicism was the state religion and the only religion that was officially allowed to be practiced. New Christians participated in the social, cultural and economic life of the colony, and were particularly active in the sugar mills in Bahia, Paraiba and Pernambuco. They could belong to official institutions such as the Brotherhood of Mercy as well as to municipal councils. Nonetheless, these New Christians faced social and economic restrictions; for example, they could not marry "Old Christians" because of the laws related to "blood purity".

During most of the colonial period, Brazil was active in the Holy Office of the Inquisition Court, which was originally established in Portugal in 1536 and eventually spread to Portugal's main colony, Brazil, where it officially functioned until 1821. The conversion of non-Catholics in the Americas (including indigenous and pre-Columbian tribes) was a central part of the process of expanding the Portuguese and Spanish Empires. The Inquisition sent representatives from Portugal to carry out investigations beginning in 1591 and delegated power to local bishops. The Inquisition's most prominent activities took place between 1591 and 1593 in the states of Bahia; between 1593 and 1595 in Pernambuco; in 1618, in Bahia; around 1627 in the southeast of Brazil; and between 1763 and 1769 in the Grand-Para (northern Brazil). In the 18th century, the Inquisition was also active in the states of Paraíba, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais.

In 1773, during the administration of the Marquess of Pombal, the distinctions between "New" and "old" Christians were abolished and the Inquisition ceased its activities. New Christians were able to integrate socially and economically into Brazilian society, while may also maintained elements of their Jewish heritage.

According to Wiznitzer, during the two and a half centuries that the Inquisition was active in Brazil, about 25,000 people were prosecuted and 1,500 were sentenced to death. About 400 people were accused of "Judaizing practices" and most were given prison sentences; 18 were deported to Lisbon where they were sentenced to death. The anti-Semitism of the Inquisition remained seeped into Brazil's cultural consciousness, though the Jews who arrived in Brazil during the 19th and 20th centuries experienced significantly less anti-Semitism than many of their coreligionists throughout the world.

Three well-known New Christian writers have excelled in the colonial period whose work during the colonial period reveals Jewish elements were Bento Teixeira, who wrote Prosopopéia during the 16th century; Ambrose Fernandes Brandão, the author of Dialogues of the Magnitudes of Brazil who also wrote during the 16th century, and the playwright Antonio Jose da Silva, "the Jew", who lived in both Portugal and Brazil and was sentenced to death by the Inquisition in 1739.

FIRST JEWISH COMMUNITY

The first organized Jewish community was formed in Recife, Pernambuco, in the northeast of the territory region, between 1630 and 1654. It took place during the period of Dutch occupation of Brazil (1630-1654), when Brazilians were granted religious freedom and both Jews and New Christians were provided with legal protections. According to Wiznitzer, the number of Jews in Brazil in 1644 reached 1,450.

In 1636 the Jews of Recife founded Kahal Kadosh Zur Israel (Rock of Israel), the first synagogue not only in Brazil, but in the Americas. The country's first Jewish cemetery was established in 1848 in Manaus.

RABBI SHALOM EMANUEL MUYAL

Many of those who arrived at the end of the 19th century and established Jewish communities sought to take advantage of Brazil's booming rubber industry. Cametá, a city in the state of Pará, eventually had half of its white population consisting of Sephardic Jews.

With significant number of Moroccan Jews moving to the Amazon because of the rubber boom, rabbinic authorities in Morocco saw the need for that community to have some form of religious leadership. At the turn of the twentieth century religious authorities in Morocco decided to send a rabbi to the Amazon, ostensibly to raise funds for a yeshiva, but with the added mission of monitoring compliance among the Moroccan Jews of the Amazon with religious norms and precepts. Rabbi Shalom Emanuel Muyal arrived in Manaus, the capital of Amazonas, in 1908 or 1910 and died two years after his arrival, probably after contracting yellow fever. Interestingly, after his death local Catholics began to revere Rabbi Muyal as a saint. Because there was no local Jewish cemetery, Rabbi Muyal was buried in the Christian cemetery and his grave became a pilgrimage site. Jealous and uncomfortable with the attention that the grave was receiving, the rabbi of the Manaus synagogue built a wall around the tomb. Rather than reducing the number of pilgrims, however, this only served to intensify the numbers of visitors to Rabbi Muyal's graves; these pilgrims also began leaving offerings and prayers on the newly-built wall. "He became the Jewish saint of the Amazon Catholics," acknowledges Isaac Dahan of the Manaus synagogue. In the 1960s, when Rabbi Muyal's nephew (who was then a minister in the Israeli government of the State of Israel) tried to exhume his uncle's remains and reinter them in the Jewish cemetery, protests erupted and the Amazonas state government requested that the body not be moved. Finally, it was agreed that the grave of Rabbi Muyal would be moved to the adjoining Jewish cemetery and the rabbi continued to be venerated among the Catholics of the Amazon.

With the decline of the rubber boom, wealthier Jewish families moved from Amazonas in northwestern Brazil to Rio de Janeiro. These families, the vast majority of whom were Sefardic, brought with them many religious ideas and elements that they absorbed and integrated from the indigenous tribes and African slaves among whom they lived.

THE MODERN PERIOD (1822-1889)

After Brazil achieved independence in 1822, the subsequent Constitution of 1824 maintained Catholicism as the state religion, but proclaimed tolerance for other religions and permitted services to be held privately. A few dozen Jews came to Brazil in this period. Dom Pedro II, who ascended the throne in 1832 and is considered by some to be one of the greatest Brazilians of all time, was an intellectual who, among other topics, was interested in Judaism and knew how to read and speak Hebrew. His travels took him to Eretz Yisrael, and he corresponded with a number of distinguished Jews.

The country's second Jewish community was founded in Belem (Bethlehem), a city in the state of Para in northern Brazil, by Jewish immigrants from Morocco. Attracted by the rubber boom, they established the Shaar Hashamaim synagogue around 1824, which has become the oldest continuously running synagogue in Brazil. A cemetery was founded in Bethlehem in 1842.

Another rubber boom that took place between the late 19th and early 20th centuries attracted more immigrants. New Jewish communities were formed in various parts of the state of Amazon, including Itacoatiara, Cametá, Paratintins, Obidos, and Santarem Humaita. Jewish immigrants also arrived in cities including Rio de Janeiro, where they foundedthe Union Shel Guemilut Hassadim during the 1840s and the Alliance Israelite Universelle in 1867. São Paulo also experienced a small influx of immigrants from Alsace-Lorraine during this period.

The Republican Constitution of 1891 guaranteed the separation of church and state and freedom of religion; among its innovations was the introduction of civil marriage and of secular cemeteries. The first organized immigration of the 20th century was to Rio Grande do Sul. Through the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA) and agreements with the state government, hundreds of immigrants from Eastern Europe settled in agricultural colonies beginning in 1893; among the colonies that were established was one in Philippson, in the region of Santa Maria, where 37 families from Bessarabia settled on 4,472 hectares in 1904.

JEWISH POPULATION AND IMMIGRATION

Beginning in the late 19th century, and particularly after the abolition of slavery in 1888, Brazil became a "nation of immigrants," attracting immigrants by offering religious tolerance, the ability to fully integrate both socially and culturally, as well as opportunities for economic advancement, that were not prevented by prejudice and racism. Between the 1880s and the 1940s Brazil became home to approximately four million immigrants, 65,000 of whom were Jews.

These immigrants, their culture, and their social and economic dynamism, contributed significantly to the country's development. In addition to the official religious freedom, Brazilian legislation was tolerant of European immigrants, and there were legislation gaps that let in increasing numbers of immigrants, in spite of the necessary legal wrangling and the requirement to obtain "call letters" to enter in the country. Brazil became a particularly desirable destination for immigrants during the 1920s, given the immigration restrictions and quotas imposed by the United States, Canada and Argentina. During the 1920s more than 10% of Jews who emigrated from Europe chose Brazil as their destination, and between 1920 and 1930 about half of the immigrants from Eastern Europe who came to Brazil were Jews.

During the First World War (1914-1918) and the interwar period, Jewish immigrants from Eastern and Western Europe and the Middle East established organized communities in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre, Curitiba, Belo Horizonte, Recife, and Salvador. Small Jewish communities were formed in dozens of towns, especially following the economic cycles that Brazil experienced since its colonization (the sugar, gold, coffee, and rubber booms). In many places, they had the support of international organizations, particularly the JCA, the Joint, Emigdirect and HIAS.

The country's Jewish population was between 5,000 and 7,000 during World War I. Approximately 30,000 Jews immigrated to Brazil during the interwar period, and the Jewish population reached about 56,000 during the 1930s.

Following are official statistics indicating the Jewish population for the years 1900, 1940 and 1950:

São Paulo: 226; 20,379; 26,443

Rio de Janeiro: 25; 22,393; 33,270

Rio Grande do Sul: 54; 6,619; 8,048

Bahia: 17; 955; 1076

Paraná: 17; 1033; 1,340

Minas Gerais: 37; 1,431; 1,528

Pernambuco: in 1920 there were about 150 Jewish families

JEWISH COMMUNITY DURING THE INTERWAR PERIOD

Communal organizations were majorly important in the successful integration of Jewish immigrants. In urban centers such as Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Porto Alegre, Salvador, Recife, Belém and Santos had charitable organizations, synagogues, schools (in 1929 there were 25 Jewish schools in Brazil), cemeteries, cultural and recreational organizations, political movements and a thriving press, which together became the center of community life. In São Paulo, for example, there were six different charities operating in the community during the 1920s, offering support to Jewish immigrants from the moment they arrived at the port, assistance to pregnant women, and even aid to those hoping to begin to work as peddlers.

In many urban centers Jewish immigrants worked as peddlers, artisans, and merchants; others worked in the textiles and furniture industries. Later, beginning in the the 1960s, a significant portion of the Jewish population entered the professional classes, and began working as doctors, managers, engineers, university professors, journalists, editors, and psychologists, among other professions.

Women also became very active in the community, particularly in institutions such as WIZO and Naamat Pioneer. They founded and directed charities that served women and children, and worked as volunteers in places such as the Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein.

Communities tended to be very politically active, and leftists and Zionist movements were especially prolific. The 1st Zionist Congress in Brazil took place in 1922 and brought together four different movements: Ahavat Sion (São Paulo), Tiferet Sion (Rio de Janeiro, established in 1919), Shalom Sion (Curitiba), and Ahavat Sion (Pará); together they formed the Zionist Federation of Brazil. A year earlier, in 1921, a Brazilian delegate attended the 12th Zionist Congress in Karlbad. In 1929, during the election to choose the Brazilian delegate to the 16th Zionist Congress the two candidates received a total of 1,260 votes; in 1934 elections to the 18th Congress, garnered a total of 2,647 votes.

Leftist movements were also significant within Jewish life in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre, Salvador, and Belo Horizonte. In Rio de Janeiro these movements centered around the Sholem Aleichem Library, the Brazkcor (Brazilian Society Pro-Jewish Colonization in the Soviet Union), and the Morris Vinchevsky Labor Center. São Paulo had active cultural and progressive groups; in 1954, the Israeli Cultural Brazilian Institute (ICIB), the House of the People, a communist organization affiliated with the Brazilian Jewish Art Theatre (TAIB) were established. Yiddish language and culture was important in connecting these movements. The first Jewish newspaper published in Yiddish in Brazil was Porto Alegre's Di Menscheit, which was first published in 1915 in Porto Alegre. Other Brazilian Jewish writers were Eliezer Levin, Samuel Malamud, Moacyr Scliar.

In São Paulo, Porto Alegre and Rio de Janeiro Jews were concentrated in the neighborhoods of Bom Retiro (before slowly moving to the Higienopolis neighborhood in São Paulo), Bonfim and Praça Onze.

During the 1920s and 1930s Jewish communities were concentrated in a few urban centers and became active economic, social and cultural centers. This rendered Brazilian Jews one of the more visible immigrant groups within Brazil. Many of the agricultural settlements that had been established by Jewish immigrants at the turn of the century challenged the perception of Jews as unproductive, or capable of working only in finance; these settlements and the goodwill they generated (in spite of their ultimate failure), helped remove restrictions on Jewish immigration to Brazil.

NEW STATE AND WORLD WAR II (1937-1945)

On the other hand, during the dictatorship of Getulio Vargas (1930-1945), Jewish visibility did become a liability, with restrictions and laws that formally prohibited Jewish immigration to Brazil; secret letters from the Foreign Ministry were revealed that discussed restricting Jewish immigration during the Second World War. The coup in 1937 that established the New State led by Vargas occurred under the false pretext of a potential communist plot, conveniently named the "Cohen Plan."

Anti-Semitism was part of a general climate of xenophobia during the period of the New State and the Second World War that was present in government circles and among the political and intellectual elites. Teaching and publishing newspapers in foreign languages was banned, and immigrant organizations had to "Brazilianize" their names and elect native Brazilians as directors. However, in spite of the dictatorship and the xenophobic nationalist environment, Jewish organizations managed to adapt to the changing political climate, and attempted to work within the restrictions imposed on them. Schools continued to teach Hebrew and Jewish culture, synagogues continued their services, radio programs persisted in playing Jewish music, and a number of organizations were even founded during this period. The period's anti-Semitism did not result in public actions taken against the Jews of Brazil or those who managed to immigrate.

Between 1933 and 1938 Brazil's fascist movement, the Brazilian Integralist Action (AIB), became active, led by Pliny Salgado, Gustavo Barroso and Miguel Reale. Anti-Semitism was part of the Integralist platform, with Barroso, the head of the militia, as the main proponent of anti-Semitism within the party. He translated "The Protocols of the Elders of Zion" and wrote anti-Semitic books, including "The Paulista Synagogue", "Brazil, Colony Bankers," and "The Secret History of Brazil." Barroso also wrote a column in the main Integralist newspaper titled "International Judaism." Nevertheless, there are no records of anti-Jewish violence during this period. Jews also fought back against the Integralists' anti-Semitism; in Curitiba, Baruch Schulman wrote an article titled "In Self Defense" in 1937 to defend Brazil's Jews. In Belo Horizonte, Isaiah Golgher created the Anti-Integralist Committee. A group of Brazilian intellectuals, supported by the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA) and the Klabin Company, published a book in in 1933 in defense of the Jews titled "Why Be Anti-Semitic? A Survey Among Brazilian Intellectuals."

Nonetheless, Jewish immigration managed to continue, mainly through negotiations that occurred on a case by case basis. About 17,500 Jews entered the country between 1933 and 1939, though many refugees from occupied Europe were denied visas and perished during the Holocaust. During this period, the Brazilian ambassador to France, Souza Dantas, saved approximately 800 people, at least 425 of whom were Jewish. In 2003 he was recognized among the Righteous of the Nations.

Brazil was neutral during World War II until 1941; the country officially entered the war against Germany and Italy in August of 1942. The Jewish communities of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro participated in the war effort. In 1942, the Jewish community of Brazil donated five aircraft for the newly created Military Aviation of Brazil, created several committees to help war refugees, and led several campaigns for refugees in Europe. Forty-two of the 30,000 men who left for Italy in July 1944 were Jewish. Jews in the Brazilian Expeditionary Force (FEB), included the artist Carlos Scliar and the author Boris Schnaiderman, both of whom used their experiences in the FEB in their work.

POSTWAR

The Jewish Federation of São Paulo State was founded in São Paulo in 1946 to organize the postwar immigration of Jewish refugees from Europe to Brazil. The Zionist movement in Brazil, which had been inactive during the war years, began to renew its activities. Jewish leftists also returned to being active, particularly in connection to the Communist Party. The Confederation of Organizations Representing the Jewish Collectivity in Brazil (later renamed the Jewish Confederation of Brazil, CONIB), was founded in 1948. Jewish institutional life flourished; the Hebrew Club was founded in São Paulo in 1953, and the Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein was opened in 1971.

The Brazilian diplomat Oswaldo Aranha presided over the meeting of the Assembly of the United Nations in 1947 when the vote was taken to recognize the creation of the State of Israel; Brazil was among those who voted for the creation of the Jewish State. Brazil recognized the State of Israel in 1949 and opened an embassy in Tel Aviv in 1952.

Between 1956 and 1957 thousands of Jews immigrated to Brazil from Egypt, North Africa (mainly Morocco), and Hungary.