The Jewish Community of New Orleans

New Orleans

A city in the state of Louisiana, USA.

A port and commercial center near the mouth of the Mississippi river in the state of Louisiana. While home to one of the largest cargo ports in the world, New Orleans is also the home to a small but vibrant Jewish community.

It may not be assumed that Jews were among the city's first settlers when it was founded in 1718, although the ''black code'' issued by the French governor in 1724 ordered their expulsion. Spanish and Portuguese Jewish traders arriving from the Caribbean were among the first to settle. The first known Jewish settler after 1724 was Isaac Rodriguez Monsanto in 1759. When the city was ceded to Spain in 1762, new and more restrictive laws were promulgated. In the early 19th century, more Jews took up residence in New Orleans, which passed to the United States with the Louisiana Purchase of 1815. Judah Touro, later a wealthy merchant and philanthropist, arrived in 1803, and Ezekiel Salomon, son of the American Revolution patriot Haym Salomon, was Governor of the United States Bank in New Orleans from 1816 to 1821. Two more Jews who later achieved high position settled in the city in 1828, Judah Benjamin, later US Secretary of State, and Henry M. Hyams, later Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana. In the 1830s Gershom Kursheedt, who became the first communal leader, arrived in New Orleans; his brother E. Isaac Kursheedt was a colonel in the Washington Artillery, the historic New Orleans regiment.

The first congregation in New Orleans to be established was Shaarei Chessed ("Gates of Mercy") synagogue. Founded in 1827 by a Sephardic Jew named Isaac Solis, it became the first permanent Jewish house of worship in the entire state of Louisiana. Not only did its foundation provide the city’s minority of religious Jews a sanctuary for prayer, but it confirmed the abolition of the Code Noir (Black Code), a decree which had originally defined the conditions of slavery and restricted the activities of freed blacks, but also forbade the practice of any religion other than Roman Catholicism and ordered all Jews out of French colonies.

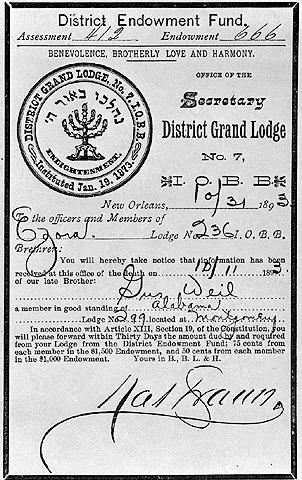

In 1848 James C. Gutheim of Cincinnati was invited to serve as rabbi. The Portuguese congregation was founded in 1846. Temple Sinai, the first reform congregation, founded in 1870, recalled Rabbi Gutheim to New Orleans from Emanu-El in New York, to be its first rabbi. The first two congregations merged in 1878 to become the reform Touro synagogue. Congregation Gates of Prayer, organized about 1850, was reform by the 1940s. The reform congregations had the largest number of members, followed by the three orthodox congregations, Chevra Tehillim (founded in 1875), Beth Israel (1903), and Agudas Achim Anshe Sfard (1896). In the early 1960s there was one conservative congregation in New Orleans, which represented about 150 families. The young Jewish society was founded in 1880 and the YMHA, in 1891. In 1910, 18 separate Jewish welfare and charity organizations merged to form the Jewish Welfare Federation.

Among some of the prominent Jews of New Orleans in the late 19th and 20th centuries were the attorney Monte M. Lemann from Louisiana; Isaac Delgado, for whom the municipal art museum was named; Martin Behrman, who was Jewish by birth, was mayor of the city for four terms 1904-1920; Samuel Zemurray, president of the United Fruit Company; Captain Neville Levy, Chairman of the Mississippi River Bridge Commission; and Percival Stern (1880-), benefactor of Tulane and Loyola universities and the Touro Infirmary, one of the South's leading medical centers. Edgar B. Stern and his wife provided many institutions and schools. Malcolm Woldenberg funded the creation of Woldenberg Park. Jews have served as presidents and board members of practically all cultural, civic, and social-welfare agencies and were charter members of some of the most exclusive social and Mardi Gras clubs, though the latter were later closed to Jews.

In 1967 the estimated population totaled 1,000,000, of which about 10,000 were Jews. New Orleans received little of the Eastern-European Jewish immigration to America and consequently has had a high percentage of third- and fourth-generation natives among its Jewish population, which has always been well integrated into the city's general life. In the 1960s, approximately half of the Jewish community belonged to the three reform synagogues. A study in 1958 showed that 25% of New Orleans' Jews were engaged in professional occupations, 40% in managerial jobs, and 18% in clerical and sales work. Relations with the non-Jewish community have traditionally been good and there was little anti-Semitism until the desegregation struggles of the 1950s and 1960s, when the anti-African-American sentiment aroused some anti-Jewish feelings as well.

Early 21st Century

Following the disruption of Hurricane Katrina, the city of New Orleans lost nearly twenty-five percent of its Jewish population, reducing their numbers to approximately seven thousand people. In an effort to revitalize the Jewish community, the Jews of New Orleans reached out to those in neighboring communities and elsewhere; in response, as many as two thousand Jews relocated to New Orleans.

Since 2006, all but one of the city’s major synagogues has reopened. Known as Congregation Beth Israel, it was New Orleans’ oldest and most prominent Orthodox synagogue. In the aftermath of Katrina, it stood submerged in over ten feet of water.

By the early 21st century, there were numerous Jewish charities and foundations, including local chapters and regional offices for larger, national and international Jewish organizations.

Such organizations include the Anti-Defamation League, the National Council of Jewish Women, Avodah: The Jewish Service Corps, Hadassah, the Jewish Endowment Foundation of Louisiana, Jewish Family Service of Greater New Orleans, the Jewish Children’s Regional Service, Sisters Chaverot and the Jewish Community Relations Council. Collectively, these organizations serve the Jewish community of New Orleans by providing a wide variety of programs, grants and social services.

Other well-known Jewish institutions like the Jewish Genealogical Society of New Orleans and Hillel’s Kitchen, a kosher restaurant and catering company, cater to the community’s religious and cultural needs.

A focal point of the Jewish community of New Orleans is the Jewish Community Center –Uptown. Established in 1855 as the Young Men’s Hebrew & Literary Society, the JCC offers a variety of programs for children, adults and families including a state-of-the-art fitness center, a four-star rated nursery school and an Alzheimer’s disease program. Additionally, the JCC sponsors several cultural events as well as summer camps, educational programs, senior exercise programs and sports leagues.

Promoting Jewish culture and the history of the Jewish experience in the American South is the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. Although located in Jackson, Mississippi, the institute works to promote Jewish culture and history through innovative programs, which educate and support Jewish communities across the South. Established in 1986 as the Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience; in 2000, the museum underwent an expansion and changed its name to the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. Since then they have continued to collect historical documents, artifacts and sacred objects in order to preserve the memory of the South’s historic Jewish communities. They additionally provide rabbinic services to small congregations throughout the region and have developed a religious school program which covers thirteen states including Louisiana.

An important cultural site in New Orleans is the New Orleans Holocaust Memorial Sculpture. Created by Yaacov Agam, an Israeli artist, it commemorates the Six Million Jews and the millions of others who perished during World War II from 1933-1945. The memorial is located in Woldenberg Park on the bank of the Mississippi.

The Reform movement in New Orleans is one of the city’s most dominant movements in Judaism. Followed by the Conservative Congregation of Shir Chadash, the Reform congregations have the largest number of members. Congregations Beth Israel and Agudas Achim Anshe Sfard are the city’s only Orthodox synagogues. Other notable congregations include the Touro Synagogue, Temple Sinai and Congregations Gates of Prayer.

In addition to various congregational Jewish schools, is the Jewish Community Day School of Greater New Orleans. Other Jewish educational programs and institutions include the Florence Melton Adult Mini-School and the Torah Academy. While the former offers classes on Judaism and is non-denominational, the latter is affiliated with Chabad. The Torah Academy provides Jewish education for students from kindergarten through the eighth grade. Catering to the city’s Jewish youth are two of New Orleans’ Jewish social associations –Camp Judaea and the B’nai Brith Youth Organization.

One of the largest Jewish enclaves was the Dryades neighborhood in New Orleans’ Lower Garden District, an area once home to a thriving community of Orthodox Jews. The Poydras and Dryades markets attracted many Jewish vendors from Poland and Russia. During the mid-20th century, Jewish populations began to move into the suburbs. A number of African American churches have since purchased the old synagogues, many of which have chosen to leave the Stars of David carvings on the buildings.

Despite the devastation of Hurricane Katrina, a number of Jewish institutions remain. There are kosher restaurants like Casablanca and the Kosher Cajun Deli; Judaica shops like Dashka Roth Contemporary Jewelry, L’Dor V’Dor Judaica, Naghi’s and M.S. Rau Antiques. There is even a bookstore at the Chabad House. The Touro Infirmary that has offered some of the best medical care in New Orleans for more than one hundred sixty years, in 2002 completed its retirement community center, which offers a variety of services for the elderly. The Touro Infirmary is New Orleans’ only non-profit, community-based and faith-based hospital.

The Jewish community of New Orleans has a long history of philanthropy. Beginning with Judah Touro, a New England Jew of Sephardic-Dutch descent, Jews have always made many contributions to the city of New Orleans.

Serving the New Orleans Jewish community are four different news and entertainment periodicals. The Jewish Light is a locally owned, published and distributed newspaper. It is New Orleans’ only local Jewish newspaper. Crescent City Jewish News offers a free weekly newsletter and the Deep South Jewish Voice is a twice-monthly newspaper that serves the Jewish communities of Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and Northwest Florida.

The Southern Jewish Life Magazine is a publication that began in 1990 under the name The Southern Shofar and serves the Jewish communities of the Southeastern United States. In 2009, it began emphasizing local content, and since 2015, they have offered two separate editions, one for the Deep South and one for New Orleans. They additionally publish a weekly newsletter known as This Week in Southern Jewish Life.