The Jewish Community of Prague

Capital of the Czech Republic. Formerly the capital of Czechoslovakia.

It has the oldest Jewish community in Bohemia and one of the oldest communities in Europe, for some time the largest and most revered. Jews may have arrived in Prague in late roman times, but the first document mentioning them is a report by Ibrahim Ibn Ya'qub from about 970. The first definite evidence for the existence of a Jewish community in Prague dates to 1091. Jews arrived in Prague from both the east and west around the same time. It is probably for this reason that two Jewish districts came into being there right at the beginning.

The relatively favorable conditions in which the Jews at first lived in Prague were disrupted at the time of the first crusade in 1096. The crusaders murdered many of the Jews in Prague, looted Jewish property, and forced many to accept baptism. During the siege of Prague castle in 1142, the oldest synagogue in Prague and the Jewish quarter below the castle were burned down and the Jews moved to the right bank of the river Moldau (vltava), which was to become the future Jewish quarter, and founded the "Altschul" ("old synagogue") there.

The importance of Jewish culture in Prague is evidenced by the works of the halakhists there in the 11th to 13th centuries. The most celebrated was Isaac B. Moses of Vienna (d. C. 1250) author of "Or Zaru'a". Since the Czech language was spoken by the Jews of Prague in the early middle ages, the halakhic writings of that period also contain annotations in Czech. From the 13th to 16th centuries the Jews of Prague increasingly spoke German. At the time of persecutions which began at the end of the 11th century, the Jews of Prague, together with all the other Jews of Europe, lost their status as free people. From the 13th century on, the Jews of Bohemia were considered servants of the royal chamber (servi camerae regis). Their residence in Prague was subject to the most humiliating conditions (the wearing of special dress, segregation in the ghetto, etc.). The only occupation that Jews were allowed to adopt was moneylending, since this was forbidden to Christians and considered dishonest. Socially the Jews were in an inferior position.

The community suffered from persecutions accompanied by bloodshed in the 13th and 14th centuries, particularly in 1298 and 1338. Charles IV (1346- 1378) protected the Jews, but after his death the worst attack occurred in 1389, when nearly all the Jews of Prague fell victims. The rabbi of Prague and noted kabbalist Avigdor Kara, who witnessed and survived the outbreak, described it in a selichah. Under Wenceslaus IV the Jews of Prague suffered heavy material losses following an order by the king in 1411 canceling all debts owed to Jews.

At the beginning of the 15th century the Jews of Prague found themselves at the center of the Hussite wars (1419- 1436). The Jews of Prague also suffered from mob violence (1422) in this period. The unstable conditions in Prague compelled many Jews to emigrate.

Following the legalization, at the end of the 15th century, of moneylending by non-Jews in Prague, the Jews of Prague lost the economic significance which they had held in the medieval city, and had to look for other occupations in commerce and crafts. The position of the Jews began to improve at the beginning of the 16th century, mainly owing to the assistance of the king and the nobility. The Jews found greater opportunities in trading commodities and monetary transactions with the nobility. As a consequence, their economic position improved. In 1522 there were about 600 Jews in Prague, but by 1541 they numbered about 1,200. At the same time the Jewish quarters were extended. At the end of the 15th century the Jews of Prague founded new communities.

Under pressure of the citizens, king Ferdinand I was compelled in 1541 to approve the expulsion of the Jews. The Jews had to leave Prague by 1543, but were allowed to return in 1545. In 1557 Ferdinand I once again, this time upon his own initiative, ordered the expulsion of the Jews from Prague. They had to leave the city by 1559. Only after the retirement of Ferdinand I from the government of Bohemia were the Jews allowed to return to Prague in 1562.

The favorable position of the Jewish community of Prague during the reign of Rudolf II is reflected also in the flourishing Jewish culture. Among illustrious rabbis who taught in Prague at that time were Judah Loew B. Bezalel (the "maharal"); Ephraim Solomon B. Aaron of Luntschitz; Isaiah B. Abraham ha-levi Horowitz, who taught in Prague from 1614 to 1621; and Yom Tov Lipmann Heller, who became chief rabbi in 1627 but was forced to leave in 1631. The chronicler and astronomer David Gans also lived there in this period. At the beginning of the 17th century about 6,000 Jews were living in Prague.

In 1648 the Jews of Prague distinguished themselves in the defense of the city against the invading swedes. In recognition of their acts of heroism the Emperor presented them with a special flag which is still preserved in the Altneuschul. Its design with a Swedish cap in the center of the Shield of David became the official emblem of the Prague Jewish community.

After the thirty years' war, government policy was influenced by the church counter-reformation, and measures were taken to limit the Jews' means of earning a livelihood. A number of anti-Semitic resolutions and decrees were promulgated. Only the eldest son of every family was allowed to marry and found a family, the others having to remain single or leave Bohemia.

In 1680, more than 3,000 Jews in Prague died of the plague. Shortly afterward, in 1689, the Jewish quarter burned down, and over 300 Jewish houses and 11 synagogues were destroyed. The authorities initiated and partially implemented a project to transfer all the surviving Jews to the village of Lieben (Liben) north of Prague. Great excitement was aroused in 1694 by the murder trial of the father of Simon Abeles, a 12-year-old boy, who, it was alleged, had desired to be baptized and had been killed by his father. Simon was buried in the Tyn (Thein) church, the greatest and most celebrated cathedral of the old town of Prague. Concurrently with the religious incitement against the Jews an economic struggle was waged against them.

The anti-Jewish official policy reached its climax after the accession to the throne of Maria Theresa (1740-1780), who in 1744 issued an order expelling the Jews from Bohemia and Moravia. Jews were banished but were subsequently allowed to return after they promised to pay high taxes. In the baroque period noted rabbis were Simon Spira; Elias Spira; David Oppenheim; and Ezekiel Landau, chief rabbi and rosh yeshivah (1755-93(.

The position of the Jews greatly improved under Joseph II (1780-1790), who issued the Toleranzpatent of 1782. The new policy in regard to the Jews aimed at gradual abolition of the limitations imposed upon them, so that they could become more useful to the state in a modernized economic system. At the same time, the new regulations were part of the systematic policy of germanization pursued by Joseph II. Jews were compelled to adopt family names and to establish schools for secular studies; they became subject to military service, and were required to cease using Hebrew and Yiddish in business transactions. Wealthy and enterprising Jews made good use of the advantages of Joseph's reforms. Jews who founded manufacturing enterprises were allowed to settle outside the Jewish quarter of Prague.

Subsequently the limitations imposed upon Jews were gradually removed. In 1841 the prohibition on Jews owning land was rescinded. In 1846 the Jewish tax was abolished. In 1848 Jews were granted equal rights, and by 1867 the process of legal emancipation had been completed. In 1852 the ghetto of Prague was abolished. Because of the unhygienic conditions in the former Jewish quarter the Prague municipality decided in 1896 to pull down the old quarter, with the exception of important historical sites. Thus the Altneuschul, the Pinkas and Klaus, Meisel and Hoch synagogues, and some other places of historical and artistic interest remained intact.

In 1848 the community of Prague, numbering over 10,000, was still one of the largest Jewish communities in Europe (Vienna then numbered only 4,000 Jews). In the following period of the emancipation and the post- emancipation era the Prague community increased considerably in numbers, but did not keep pace with the rapidly expanding new Jewish metropolitan centers in western, central, and Eastern Europe.

After emancipation had been achieved in 1867, emigration from Prague abroad ceased as a mass phenomenon; movement to Vienna, Germany, and Western Europe continued. Jews were now represented in industry, especially the textile, clothing, leather, shoe, and food industries, in wholesale and retail trade, and in increasing numbers in the professions and as white-collar employees. Some Jewish bankers, industrialists and merchants achieved considerable wealth. The majority of Jews in Prague belonged to the middle class, but there also remained a substantial number of poor Jews.

Emancipation brought in its wake a quiet process of secularization and assimilation. In the first decades of the 19th century Prague Jewry, which then still led its traditionalist orthodox way of life, had been disturbed by the activities of the followers of Jacob Frank. The situation changed in the second half of the century. The chief rabbinate was still occupied by outstanding scholars, like Solomon Judah Rapoport, the leader of the Haskalah movement; Markus Hirsch (1880-1889) helped to weaken the religious influence in the community. Many synagogues introduced modernized services, a shortened liturgy, the organ and mixed choir, but did not necessarily embrace the principles of the reform movement.

Jews availed themselves eagerly of the opportunities to give their children a higher secular education. Jews formed a considerable part of the German minority in Prague, and the majority adhered to liberal movements. David Kuh founded the "German liberal party of Bohemia and represented it in the Bohemian diet (1862-1873). Despite strong Germanizing factors, many Jews adhered to the Czech language, and in the last two decades of the 19th century a Czech assimilationist movement developed which gained support from the continuing influx of Jews from the rural areas. Through the influence of German nationalists from the Sudeten districts anti-Semitism developed within the German population and opposed Jewish assimilation. At the end of the 19th century Zionism struck roots among the Jews of Bohemia, especially in Prague.

Growing secularization and assimilation led to an increase of mixed marriages and abandonment of Judaism. At the time of the Czechoslovak republic, established in 1918, many more people registered their dissociation of affiliation to the Jewish faith without adopting another. The proportion of mixed marriages in Bohemia was one of the highest in Europe. The seven communities of Prague were federated in the union of Jewish religious communities of greater Prague and cooperated on many issues. They established joint institutions; among these the most important was the institute for social welfare, established in 1935. The "Afike Jehuda society for the Advancement of Jewish Studies" was founded in 1869. There were also the Jewish museum and "The Jewish historical society of Czechoslovakia". A five-grade elementary school was established with Czech as the language of instruction. The many philanthropic institutions and associations included the Jewish care for the sick, the center for social welfare, the aid committee for refugees, the aid committee for Jews from Carpatho- Russia, orphanages, hostels for apprentices, old-age homes, a home for abandoned children, free-meal associations, associations for children's vacation centers, and funds to aid students. Zionist organizations were also well represented. There were three B'nai B'rith lodges, women's organizations, youth movements, student clubs, sports organizations, and a community center. Four Jewish weeklies were published in Prague (three Zionist; one Czech- assimilationist), and several monthlies and quarterlies. Most Jewish organizations in Czechoslovakia had their headquarters in Prague.

Jews first became politically active, and some of them prominent, within the German orbit. David Kuh and the president of the Jewish community, Arnold Rosenbacher, were among the leaders of the German Liberal party in the 19th century. Bruno Kafka and Ludwig Spiegel represented its successor in the Czechoslovak republic, the German Democratic Party, in the chamber of deputies and the senate respectively. Emil Strauss represented that party in the 1930s on the Prague Municipal Council and in the Bohemian diet. From the end of the 19th century an increasing number of Jews joined Czech parties, especially T. G. Masaryk's realists and the social democratic party. Among the latter Alfred Meissner, Lev Winter, and Robert Klein rose to prominence, the first two as ministers of justice and social welfare respectively.

Zionists, though a minority, soon became the most active element among the Jews of Prague. "Barissia" - Jewish Academic Corporation, was founded in Prague in 1903, it was one of the leading academic organizations for the advancement of Zionism in Bohemia. Before World War I the students' organization "Bar Kochba", under the leadership of Samuel Hugo Bergman, became one of the centers of cultural Zionism. The Prague Zionist Arthur Mahler was elected to the Austrian parliament in 1907, though as representative of an electoral district in Galicia. Under the leadership of Ludvik Singer the "Jewish National Council" was formed in 1918. Singer was elected in 1929 to the Czechoslovak parliament, and was succeeded after his death in 1931 by Angelo Goldstein. Singer, Goldstein, Frantisek Friedmann, and Jacob Reiss represented the Zionists on the Prague municipal council also. Some important Zionist conferences took place in Prague, among them the founding conference of hitachadut in 1920, and the

18th Zionist congress in 1933.

The group of Prague German-Jewish authors which emerged in the 1880s, known as the "Prague Circle" ('der Prager Kreis'), achieved international recognition and included Franz Kafka, Max Brod, Franz Werfel, Oskar Baum, Ludwig Winder, Leo Perutz, Egon Erwin Kisch, Otto Klepetar, and Willy Haas.

During the Holocaust period, the measures e.g., deprivation of property rights, prohibition against religious, cultural, or any other form of public activity, expulsion from the professions and from schools, a ban on the use of public transportation and the telephone, affected Prague Jews much more than those still living in the provinces. Jewish organizations provided social welfare and clandestinely continued the education of the youth and the training in languages and new vocations in preparation for emigration. The Palestine office in Prague, directed by Jacob Edelstein, enabled about 19,000 Jews to emigrate legally or otherwise until the end of 1939.

In March 1940, the Prague zentralstelle extended the area of its jurisdiction to include all of Bohemia and Moravia. In an attempt to obviate the deportation of the Jews to "the east", Jewish leaders, headed by Jacob Edelstein, proposed to the zentralstelle the establishment of a self- administered concentrated Jewish communal body; the Nazis eventually exploited this proposal in the establishment of a ghetto at Theresienstadt (Terezin). The Prague Jewish community was forced to provide the Nazis with lists of candidates for deportation and to ensure that they showed up at the assembly point and boarded deportation trains. In the period from October 6, 1941, to March 16, 1945, 46,067 Jews were deported from Prague to "the east" or to Theresienstadt. Two leading officials of the Jewish community, H. Bonn and Emil Kafka were dispatched to Mauthausen concentration camp and put to death after trying to slow down the pace of the deportations. The Nazis set up a treuhandstelle ("trustee Office") over evacuated Jewish apartments, furnishings, and possessions. This office sold these goods and forwarded the proceeds to the German winterhilfe ("winter aid"). The treuhandstelle ran as many as 54 warehouses, including 11 synagogues (as a result, none of the synagogues was destroyed). The zentralstelle brought Jewish religious articles from 153 Jewish communities to Prague on a proposal by Jewish scholars. This collection, including 5,400 religious objects, 24,500 prayer books, and 6,070 items of historical value the Nazis intended to utilize for a "central museum of the defunct Jewish race". Jewish historians engaged in the creation of the museum were deported to extermination camps just before the end of the war. Thus the Jewish museum had acquired at the end of the war one of the richest collections of Judaica in the world.

Prague had a Jewish population of 10,338 in 1946, of whom 1,396 Jews had not been deported (mostly of mixed Jewish and Christian parentage); 227 Jews had gone underground; 4,986 returned from prisons, concentration camps, or Theresienstadt; 883 returned from Czechoslovak army units abroad; 613 were Czechoslovak Jewish emigres who returned; and 2,233 were Jews from Ruthenia (Carpatho-Ukraine), which had been ceded to the U.S.S.R. who decided to move to Czechoslovakia. The communist takeover of 1948 put an end to any attempt to revive the Jewish community and marked the beginning of a period of stagnation. By 1950 about half of the Jewish population had gone to Israel or immigrated to other countries. The Slansky trials and the officially promoted anti-Semitism had a destructive effect upon Jewish life. Nazi racism of the previous era was replaced by political and social discrimination. Most of the Jews of Prague were branded as "class enemies of the working people". During this

Period (1951-1964) there was no possibility of Jewish emigration from the country. The assets belonging to the Jewish community had to be relinquished to the state. The charitable organizations were disbanded, and the budget of the community, provided by the state, was drastically reduced. The general anti-religious policy of the regime resulted in the cessation, for all practical purposes, of such Jewish religious activities as bar-mitzvah religious instruction and wedding ceremonies. In 1964 only two cantors and two ritual slaughterers were left. The liberalization of the regime during 1965-1968 held out new hope for a renewal of Jewish life in Prague.

At the end of March 1967 the president of "The World Jewish Congress", Nahum Goldmann, was able to visit Prague and give a lecture in the Jewish town hall. Among the Jewish youth many tended to identify with Judaism. Following the soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 there was an attempt to put an end to this trend, however the Jewish youth, organized since 1965, carried on with their Jewish cultural activities until 1972. In the late 6os the Jewish population of Prague numbered about 2,000.

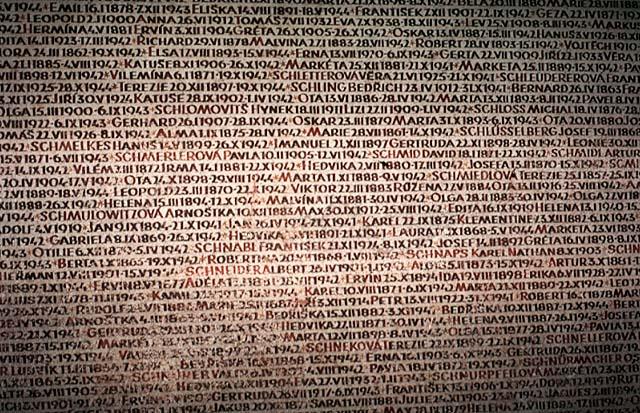

On the walls of the Pinkas synagogue, which is part of the central Jewish museum in Prague, are engraved the names of 77,297 Jews from Bohemia and Moravia who were murdered by the Nazis in 1939-1945.

In 1997 some 6,000 Jews were living in the Czech Republic, most of them in Prague. The majority of the Jews of Prague were indeed elderly, but the Jewish community's strengthened in 1990's by many Jews, mainly American, who had come to work in the republic, settled in Prague, and joined the community.

In April 2000 the central square of Prague was named Franz Kafka square. This was done thanks to the unflinching efforts and after years of straggle with the authorities, of Professor Eduard Goldstucker, a Jew born in Prague, the initiator of the idea.

Arnost Lustig

(Personality)Arnost Lustig (1926-2011), Holocaust survivor, novelist, playwright and short story writer, born in Prague, Czech Republic (then Czechoslovakia). Many of his works involved the Holocaust. According to Charfles Larson, professor of literature at the American University of Washington, DC, Lustig was “the greatest novelist of the Holocaust”.

As a 15 year-old Jewish boy, Lustig was sent to Theresienstadt Nazi concentration camp and was subsequently transported to Auschwitz and Buchenwald Nazi concentration camps. In 1945 the Nazis loaded him on a train which was due to take him to Dachau concentration camp, but he succeeded in escaping after the locomotive was bombed by an American aircraft. He then returned to Prague by foot to join the resistance movement. He participated in the May 1945 anti-Nazi uprising in Prague. Most other members of his family had been murdered by the Nazis although his mother and sister survived.

After WW 2, Lustig studied journalism in Prague University and then worked for Radio Prague as a reporter and magazine editor. While in Israel, when reporting on the Israel War of Independence, he met poetry writer Vera Weislitzova, who was a volunteer for the Haganah and whom he later married. Vera, who had also been held in Theresientstadt, was the daughter of a furniture maker from Ostrava, Czech Republic. Both of her parents were murdered in Auschwitz.

He left the Czech Communist Party in protest against his government’s breaking off relations with Israel after the 1967 Six Day War. In the summer of 1968 he was in Italy advocating the reformist view of Czech leader Alexander Dubcek when he heard that the Russians had invaded Czechoslovakia. Instead of returning home he went first to Israel, then to Yugoslavia and finally to the USA, where he accepted positions at the University of Iowa and then at the American University. After the fall of communism in 1989 he continued to teach at the American University, but lived partly in Washington DC and partly in Prague. Only in 2003 did he again become a permanent resident of Prague.

In 2006 he was honoured by Vaclav Havel, past President of the Czech Republic, for his contribution to Czech culture and in 2008 he was awarded the Franz Kafka Prize.

Some of his stories were published in the USA under the title “Children of the Holocaust”. One short story concerns with two young people running away from a train and hiding in the woods where they stole bread from a farm. They were almost executed for their crime. Probably Lustig’s best known book was "A Prayer for Katerina Horowitzowa" (1974), which tells of a group of Jewish American businessmen trapped in Nazi Germany who tried to bribe their way out of the country. The Nazis kept tricking them and they were finally murdered in the concentration camps. Among his other 20 works were "Dita Saxova" (1962), "Night and Hope" (1957), "Art from the Ashes" (1995) and "Lovely Green Eyes" (2004). "Dita Saxona" and "Night and Hope" were made into films.

Alice Herz-Sommer

(Personality)Alice Herz-Sommer (1903-2014), pianist and music teacher, born in Prague, Czech Republic (then part of Austria-Hungary). A survivor of the Nazi Theresienstadt Concentration Camp, at the age of 110 was the world's oldest known Holocaust survivor and pianist.

Her parents, Friedrich Herz, a merchant, and Sofie, who was highly educated and moved in circles of well-known writers ran a cultural salon, and as a child Herz met writers, philosophers, and composers including Gustav Mahler and Franz Kafka.

Herz had a twin sister, Mariana, and two brothers. Herz's older sister Irma taught her how to play piano, which she studied diligently, and the pianist Artur Schnabel, a friend of the family, encouraged her to pursue a career as a classical musician; a choice she decided to make.She went on to study under Václav Štěpán, at the Prague German Music Conservatory where she was the youngest pupil. Herz married the businessman and amateur musician Leopold Sommer in 1931; the couple had a son, Stephan (later known as Raphael,1937–2001).

She began giving concerts and making a name for herself across Europe until the Nazis took over Prague, as they did not allow Jews to perform in public, join music competitions or teach non-Jewish pupils. After the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovaskia, most of Herz-Sommer's family and friends emigrated to Palestine, but Herz-Sommer stayed in Prague to care for her ill mother, Sophie, aged 72, who was arrested and killed. In July 1943 Herz was sent to Theresienstadt where she played in more than 100 concerts along with other musicians, for prisoners and guards. She commented that

“We had to play because the Red Cross came three times a year. The Germans wanted to show its representatives that the situation of the Jews in Theresienstadt was good. Whenever I knew that I had a concert, I was happy. Music is magic. We performed in the council hall before an audience of 150 old, hopeless, sick and hungry people. They lived for the music. It was like food to them. If they hadn’t come [to hear us], they would have died long before. As we would also have died."

Herz-Sommer was billeted with her son during their time at the camp, he was one of only a few children to survive Theresienstadt. Her husband died of typhus in Dachau in 1944, six weeks before the camp was liberated. After the Soviet liberation of Theresienstadt in 1945, Herz and Raphael returned to Prague and in March 1949 emigrated to Israel to be reunited with some of her family, including her twin sister, Mariana. Herz lived in Israel for nearly 40 years, working as a music teacher at the Jerusalem Academy of Music until moving to London in 1986. Her son Raphael, an accomplished cellist and conductor, died in 2001, aged 64, in Israel at the end of a concert tour. He was survived by his widow and two sons.

In London, Herz-Sommer lived close to her family in a one-room flat in London visited almost daily by her closest friends, her grandson Ariel Sommer, and daughter-in-law Genevieve Sommer. She practised playing the piano three hours a day until the end of her life. She stated that optimism was the key to her life.

A film about Herz-Sommer's life,"The Lady in Number 6" won the 2014 Academy Award for the Best Short Documenrary.

Bedrich Feigl

(Personality)Bedrich Feigl (1884-1965), painter, graphic designer, and illustrator, born in Prague, Czech Republic (then part of Austria-Hungary). He studied at the Academy of Fine Art in Prague. He first exhibited in a group exhibition in 1907, in Prague.

During WW I, Feigl was a member of a team of aircraft designers, later becoming the dean of the Czechoslovak aircraft industry and was delegated to attend many conventions abroad.

Feigl was considered an avant-garde artist. In the early years of the 20th century, when the first center of contemporary avant-garde art formed in Prague, Feigl was its intellectual head. In 1928 he was a founding member of the Prague Secession.

In the history of Jewish art in Czechoslovakia, Feigl occupies a position apart. He was attracted by Jewish and biblical themes, such as Rebecca at the Well or The Finding of Moses. In addition, his landscapes include depictions of Jerusalem, The Valley of Gideon, The Valley of Kidron, places he visited during a voyage to the Land of Israel in 1932.

He lived for a long time in Berlin, New York, and London. In 1939, foillowing the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia, he was arrested and interned in a German camp. He, along with his wife, were liberated only at the intervention of the Artist's Refugee Committee and the British Consulate in Koln, Germany, and allowed to leave for England in April 1939 where they settled in London. Feigl regularly took part in group exhibitions at the London Ben Uri Art Gallery, which displayed his work on the occasion of his 75th and 80th birthday in the years 1959 and 1964, respectively.

Feigl died in London.

Franz Kafka

(Personality)Franz Kafka (1883-1924), author, born to a middle class family in Prague, Bohemia (then part of Austria-Hungary, now in the Czech Republic). Kafka was a lonely child. He studied at a German high school and then at university, becoming a doctor of law. He found positions in insurance companies, where he worked long hours and eventually had to resign owing to poor health.

From 1917 he suffered from tuberculosis and much of his life from then on was spent in Sanatoriums. He was buried in the family tomb in Prague.

Only a few of his works - and not his best known - were published during his lifetime and he left instructions to his friend and literary executor, Max Brod, to burn the remainder.

Brod disobeyed and the publication of his novels brought Kafka posthumous world fame. Best-known are his novels, "The Trial", "The Castle", and "America", all written in German. Their world of frustration and nightmarish hopelessness brought the word 'Kafkaesque' into the language.

Julius Schulhoff

(Personality)Julius Schulhoff (1825-1898), pianist and composer, born in Prague, Czech Republic (then part of the Austrian Empire). He studied in Prague, made his debut in Dresden, Germany in 1842, and then moved to Paris where he enjoyed the patronage of Chopin. His first composition, Allegro Brilliant, was dedicated to Chopin. He made a long concert tour through Austria, England, Spain and southern Russia. On his return to Paris he started teaching. With the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 he settled in Dresden. Shortly before his death he moved to Berlin. His salon music for piano (Galop di Bravura; Impromptu Polka) was very popular.

Yeshayahu Horowitz Halevy

(Personality)Yeshayahu Horowitz Halevy (1570-1630), rabbinical authority, born in Prague (now in the Czech Republic). He studied in Poland and was an outstanding Talmudist already in his youth. In 1600 he was head of the beth din in Dubno, from 1602 in Ostrog, (now in the Czech Republic) and from 1606 in Frankfurt on Main, Germany. After the Jews of Frankfurt were expelled in 1614, he became rabbi in Prague but after his wife died in 1621, he moved to the Land of Israel where he was rabbi of the Ashkenazi community. In 1625, Horowitz was imprisoned by the pasha (Ottoman governor) and held to ransom. On his release, he became rabbi of Safed. He died in Tiberias and was buried near to Maimonides. He is best known for his compendium, Shnei Lukhot ha-Berit, both he and the book being generally known by its initials, "Shelah". It contained laws of the festivals and the 613 commandments. It soon became one of the classics of rabbinic study and influenced early Hasidic thought. Horowitz was also a kabbalist and was responsible for the introduction of a number of kabbalistic prayers into the prayer book, on which he wrote a commentary.

Heinrich von Bamberger

(Personality)Heinrich von Bamberger (1822-1888), physician and teacher, born in Prague, Czech Republic (then part of the Austrian Empire, later Czechoslovakia). Bamberger studied medicine in Prague where he earned a doctorate in 1847. He worked for the General Hospital in Prague. In 1854 he was appointed professor of pathology at Wuerzburg University, Germany. He stayed on that position until 1872, when he became professor at the University of Vienna and was appointed director of a medical clinic in Vienna.

Bamberger became famous for his brilliant lectures and for his diagnostic techniques. He is especially known for his Lehrbuch der Krankheiten des Herzens ("Handbook of Diseases of the Heart," 1857), a textbook on cardiac diseases and, for his diagnoses of symptoms of cardiac diseases. His name was given to Bamberger's disease, Bamberger's bulbar pulse, and Bamberger's sign for pericardial effusion. He advocated the use of albuminous mercuric solution in the therapy of syphilis and reported albuminuria during the latter period of severe anemia. He also described muscular atrophy and hypertrophy.

In 1887, Bamberger and Ernst Fuchs founded the Wiener klinische Wochenschrift . During the last two years of his life, Bamberger served as President of the Vienna Medical Association.

He was the father of the internist Eugen von Bamberger.

Jiri Langer

(Personality)Jiri Langer (1894-1943) Czech and Hebrew poet.

A younger brother of the playwright, Frantisek Langer, he was born in Prague. He rejected his milieu of assimilation and after visiting Erets Israel in 1913 went to Belz where stayed for a few years at the court of the rabbi of Belz. Returning to Prague, he continued his observant lifestyle, including the hasidic garb. When World War I broke out Langer returned to Belz but was conscripted into the Austrian army; he was released because of his religious stringency. He then taught at a Jewish school and published Hebrew poetry. He also wrote books in German applying psychoanalysis to aspects of Jewish literature. Langer is best known for his Czech writings including poetry and hasidic stories. He was very friendly with Franz Kafka whom he taught Hebrew. After the Germans took over Prague in 1938, he escaped to Palestine where he wrote a further volume of Hebrew poetry.

Isidor Bush (Busch)

(Personality)Isidor Bush (Busch) (1822-1898), publisher and viticulturist, and American frontier pioneer, born in Prague, Czech Republic (then part of the Austrian Empire, later Czechoslovakia). Bush never attended school or college, but was educated by private teachers and Jewish scholars. He was introduced into the printing business as an employee in his father's plant in Vienna, Austra. Already when he was 15 years of age, he was intrumental in helping to set up an edition of the Talmud. He became the youngest publisher in Vienna. Eventually, the firm of Von Schmid & Bush became the largest Hebrew publishing house in the world.

In 1842 he initiated the "Jahrbuch fuer Israeliten", the first almanac by Jewish authors for a Jewish public. Together with I. S. Reggio he published the Hebrew-German "Bikkurei ha-Ittim ha-Hadashim" (one issue, Vienna, 1845), in which he emphasized the need to learn and use the Hebrew language.

Following the repression of the 1848 revolutions, Bush left the Austrian Empire and immigrated to the USA settling in New York in 1949. He founded a book store and publishred for three months "Israels Herald" (in German), the first American Jewish weekly.

Bush moved to St. Louis, where he opened a general store in partnership with his brother-in-law, Charles Taussig, and began to prosper. In 1857 founded the People's Savings Bank, and served as its president until 1863.

During the American Civil War, Bush was appointed aide to Unionist General John C. Frémont in 1861, serving with the rank of captain until 1862. Bush was named general agent of the St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad and held that position until 1868. In 1864 he was one of the St. Louis delegates to the Missouri Constitutional Convention, and served as a member of the State Board of Immigration from 1865 to 1877.

During the later years of his life he won wide recognition as a viticulturist, planting vineyards in Bushberg, in Jefferson County MO, a large tract of land on the immediate outskirts of St, Louis that he purchased in 1851. He published the Bushberg Catalogue, a manual on grape-growing that later on was translated into many languages. In 1870, Isador Bush created the firm of Isidor Bush & Co. – a wine and liquor business.

Bush was one of the founders of B'nei El Temple, in St. Louis, and of the Cleveland Orphan Asylum (1868). In 1873 he was elected grand president of the St. Louis lodge of the B'nai B'rith. Bush was an active member and vice-president (1882) of the Missouri Historical Society.

Bush died in St. Louis in 1898.

Otto Petschek

(Personality)Otto Petschek (1882-1934), industrialist and banker, a member of the Petschek family - the son of Isidor Petschek, one of the owners and managers of a coal mining and other industrial interests, known as "Grosser Petschek", born in Prague, Czech Republic (then part of Austria-Hungary, later in Czechoslovakia).

After his father's death in 1919, Otto became head of the Petschek concern for a short period. In 1934, Otto Petschek died in a sanatorium in Vienna, Austria. He was survived by his wife Martha (nee Popper), a son Victor, and three daughters, Eva, and the twin sisters Rita and Ina-Louise, who immigrated to Toronto, Canada, in 1938.

Otto Petschek's mansion in Prague, built in the late 1920's, inspired by French Baroque, was occupied by the Nazis during World War II and served as their headquarters.