The Jewish Community of St. Louis, MO

St. Louis

St. Louis is home to the largest Jewish community in the state of Missouri, USA.

A 1995 demographic study conducted by Gary A. Tobin found that the Jewish population of Greater St. Louis was 59,400. Subsequent studies, including one from 2014, have estimated the number of Jewish people living in St. Louis to be between 55,000 and 61,000, nearly 2% of the total population. The Jewish community of St. Louis is mostly made up of descendants of Jews who immigrated to the United States from Germany during the first three decades of the 19th century; Jews from Eastern Europe arrived shortly thereafter.

Over the years, much of the Jewish population has moved away from the city's center. Small Jewish communities have developed in neighborhoods such as Chesterfield, Wildwood, Olivette, and Creve Coeur. University City had once been the heart of St. Louis' Jewish community and while many Jewish families have moved, a sizeable Orthodox community has remained.

The Jews of St. Louis are served by more than fifty organizations and associations, including the Jewish Federation, the community's central agency. Established in 1901, the Federation is one of the oldest nonprofit organizations in the entire region. It supports youth groups, cultural programs, and six Jewish day schools. Its Annual Community Campaign, the largest of its fundraising efforts, distributes donations to over fifty local and national agencies. These agencies promote Jewish identity, support Jewish causes, combat anti-Semitism, and offer a wide range of services and programs such as health care, education and social services. The Ben-Gurion Society, a partner agency of the Federation, focuses its efforts on philanthropy and community development, providing young Jewish professionals with the tools to strengthen Jewish traditions and values. Several national organizations such as Hadassah, the National Council of Jewish Women and the Jewish National Fund all have chapters and local branches in St. Louis. Other notable organizations include JProStL, the Central Agency for Jewish Education (CAJE) and the Milestone Institute.

The most significant Jewish cultural institution in St. Louis is the Holocaust Museum & Learning Center. Opened in 1995, the HMLC is the city's largest resource for Holocaust Education. In 2012, it added an interactive exhibit which focuses on confronting hate and discrimination in a post-Holocaust world. Its video library and oral history project features more than one hundred personal testimonies. The HMLC also includes a Holocaust memorial, the Garden of Remembrance.

Another location of Jewish historical significance is the Military Museum, located in the Jewish Federation building. Commemorating close to three hundred sixty years of Jewish service in America's military, the Museum includes a number of artifacts and photo albums as well as a memorial known as the "Wall of Honor". On this wall is a list which contains the names of close to one thousand St. Louis-area servicemen recognized for their heroic wartime actions.

In addition to the city's museums, Jewish gift shops, and historic synagogues are several Jewish landmarks which speak of the community's rich history and experience in St. Louis. One in particular is the building which houses the Missouri Historical Society's Library and Collections Center. Between 1924 and 1927, this building, constructed in a Byzantine design, was home to the United Hebrew Temple.

The Gateway Arch Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, the St. Louis Union Station, and Forest Park are key tourist attractions and all the result of Jewish contributions. The Gateway Arch was the site of Max's Grocery Store, where Jews worshipped for the first time west of the Mississippi. Other landmarks include the JCC's Art Gallery and the St. Louis Walk of Fame, which includes ninety famous people from St. Louis, ten of whom are Jewish.

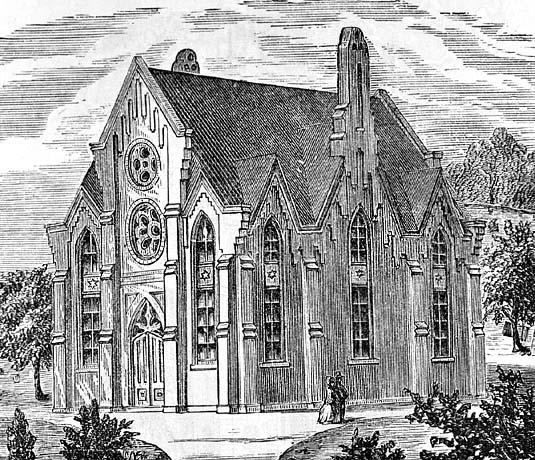

There are about two dozen synagogues in the Greater St. Louis area. While the vast majority (90%) of the Jewish community identifies as Reform or Conservative, the city is home to congregations affiliated with nearly every movement within Judaism, including Reconstructionist and Jewish Renewal. The first Jewish religious service to be held in St. Louis was in 1836 on the Jewish New Year in a rented room above a local grocery store. The ten men who gathered would go on to organize the city's first synagogue, the Hebrew Congregation. After conducting services in a used building, the congregation purchased a site to build their own in 1855. The building, located on Sixth Street, was officially consecrated in 1859.

In addition to the educational programming provided by the city's congregations, there are eight early childhood education centers, seven day schools and various programs which offer courses on Jewish studies. Aish HaTorah, the Chabad centers, and the Jewish Community Center all provide educational opportunities among their many services. The Rohr Jewish Learning Institute (JLI) offers adult courses on Jewish history, law, ethics, philosophy, and rabbinical literature. By 2014, there were close to 118,000 students enrolled at JLI.

Outside of the classroom, Jewish students and young adults can participate in a variety of social programs such as the Moishe House, BBYO, Next Dor and the Jewish Student Union. The YPD is an organization for post-college Jewish men and women which offers direct-service projects, educational programs and leadership development activities.

Serving both the Jewish and non-Jewish community of St. Louis is the Barnes-Jewish Hospital, the largest hospital in the state of Missouri. Barnes Hospital opened in 1914; the Jewish Hospital was founded in 1902 by several leaders in the Jewish community in order to provide health care for the city's poor. The hospital was built on Delmar Boulevard but moved within two blocks of Barnes Hospital in 1927. In 1996, the two merged, forming Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

First published in 1947, the St. Louis Jewish Light is St. Louis' weekly Jewish newspaper. Since 2007, the publication has had a circulation of more than fourteen thousand households and a readership of about fifty thousand.

HISTORY

St. Louis was founded in 1764 by Pierre Laclede, a French fur trader from New Orleans. Since St. Louis was, at that time, under French rule and was therefore subject to the regulations governing French colonial territories, non-Catholic settlement was forbidden in the city. No Jews are known to have settled in St. Louis until 1804, after the Louisiana Purchase which transferred control of the city from France to the US.

Joseph Philipson, the first Jew who is known to have settled in the city, opened a store in St. Louis in 1807. It took another 30 years, however, for the city's Jewish community to begin to develop significantly. The first High Holidays services were held in 1837, and the first Jewish cemetery was opened in 1841. That same year saw the establishment of The United Hebrew Congregation by a group of men from Posen (Prussia), Bohemia, and England. Shortly thereafter, in 1842, the Hebrew Benevolent Society was formed to care for the city's needy Jews.

Not all of the Jews of St. Louis were traditional, and so were not satisfied by United Hebrew Congregation. Consequently, a group of German immigrants founded two less traditional congregations: Emanu-El, which opened in 1847, and B'nai Brith, which opened in 1849. The "Daily Missouri Republican" commented in 1849 that one group was stricter in matters of eating non-kosher meat at local cafes and in keeping their businesses open on Saturdays. In 1851 Rabbi Isaac Lesser attempted to merge all three congregations and create a larger, more stable, Jewish community. Though the merger fell through, Emanu-El and B'nai Brith did merge in 1852 to form B'nai El which, thanks to a bequest by Judah Touro, constructed the first synagogue in St. Louis. Its constitution stated that it would not condemn or exclude anyone for their religious or "irreligious" views. In the meantime, United Hebrew Congregation founded a Hebrew Day School in 1851, and a mikvah in 1862.

In 1854, Rabbi Bernard Illowy became the first rabbi of United Hebrew Congregation. His tenure there, however, would not last long. Further divisions over observance levels led to the formation of another congregation, Adas Yeshurun. A year later, Rabbi Illowy resigned, citing "philosophical differences" with the congregation. When Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise visited the city in 1855, he found that only a fraction of the local Jews, mainly the less-educated, was affiliated with a congregation.

In spite of the progress that was taking place, the Jewish community nonetheless remained small; between 1848 and 1853 the Jewish population in St. Louis was between 600-700 mostly German Jews. A number of factors may have been responsible for the slow pace of growth within the Jewish community: the St. Louis Fire of May 1849, the cholera epidemic that followed during the summer of that year, and the Gold Rush, which lured many people further west, to California.

The period following the Civil War saw an increased local interest in Reform Judaism. The mid-1960s saw the formation of the St. Louis Temple Association, to be called the Sha'arei Emeth Congregation, which was the first Reform synagogue in the area. Its rabbi, Rabbi Solomon H. Sonnenschein, became well-known locally; during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, Rabbi Sonnenschein attended local German rallies to help raise funds for the fatherland. Additionally, at least three Orthodox congregations were founded between 1870-1879. The United Hebrew Relief Association was founded to help newcomers arriving from areas affected by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

Though the majority-German Jews who had been living in St. Louis sent letters to New York specifically requesting that Eastern European immigrants not be sent to St. Louis, the new immigrants arrived anyway and most settled on the poorer North Side of the city. During the 1890s, a branch of the Jewish Alliance of America was established in St. Louis in order to assist in the acculturation and education of the Eastern European arrivals. The Alliance, as well as the Hebrew Free and Industrial School opened night classes for the immigrants, provided daycare for the children of working mothers, and helped immigrants with job placement.

By 1899, the Jewish Alliance and the United Hebrew Relief Association had been combined into one agency, the United Jewish Educational and Charitable Association. Other benevolent organizations founded at the turn of the 20th century were the Jewish hospital, which had purchased a building in 1902, the YMHA-YWHA, the Jewish Orphans Home, and an Orthodox center for the aged.

The Jewish community of St. Louis embraced Zionism; due to the efforts of Zionist groups, the Zionist flag (an early version of what would later become the flag of the State of Israel) flew alongside the flags of other nations during the St. Louis World's Fair of 1904. In 1911, several locals sponsored the settled of Poriah, near Lake Kineret, in Palestine; 13 mostly-Orthodox members of the St. Louis community settled there until World War I and the harsh political and physical conditions forced the group to leave. Nonetheless, very few of the old settlers of city were Zionists, with the notable exception of Rabbi Mendel Silber of United Hebrew Congregation, nor were the Reform Jews supportive of the movement. With the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, however, most opponents became ardent supporters of the Jewish State.

In 1924, a number of rabbis and laymen from the Orthodox and Conservative movements organized a Va'ad Ha'ir (City Organization) to deal with kashrut and other Jewish concerns. Two years later, five Jewish schools were organized under the umbrella of the Associated Hebrew Schools. Hebrew was also taught in one of the public high schools. The Va'ad Ha'ir was led by the Orthodox rabbi, Rabbi Chaim Fischel Epstein. Later, in 1943, the first Jewish day school in St. Louis opened: the Chaim Fischel Epstein Hebrew Academy, named after Rabbi Epstein. A Hillel was opened in 1946.

During the Nazi era, the Jewish community Relations Council was formed to defend local Jewry against anti-Semitic accusations. Though there had been no major anti-Semitic incidents in the city, there was a great deal of bias against Jews. Throughout the 150 years that passed since the first Jews arrived in the city, Jews were seldom elected to high local or state political positions; notable exceptions were Nathan Frank, a Republican member of the House of Representative, Louis P. Aloe, the acting mayor of St. Louis, and Lawrence Roos, the Republican supervisor of St. Louis County. Most of the Jews who reached the highest positions did so in companies or organizations that were founded or owned by other Jews. The largest industries in St. Louis were aircraft, chemicals, and beer; none of these industries had Jews in top executive positions.

After World War II the St. Louis Jewish community, which had been made up of immigrants, first from Germany and then from Eastern Europe, became more Americanized and slowly found greater acceptance in the city. In addition to finding greater acceptance within St. Louis, the Jewish community has worked to maintain their ties with each other and their Jewish heritage. In 1954, the St. Louis Rabbinical Association was founded, allowing rabbis and congregations from across the denominational spectrum to provide each other with information and support.

In 1970, there were an estimated 57,700 Jews living in St. Louis, representing 2.3% of the total population of the city. A demographic study conducted in 1982 showed that 74% of St. Louis Jews were affiliated with a Jewish organization, 85% were born in the US, and a very high percentage were college graduates.

Isidor Bush (Busch) (1822-1898), publisher and viticulturist, and American frontier pioneer, born in Prague, Czech Republic (then part of the Austrian Empire, later Czechoslovakia). Bush never attended school or college, but was educated by private teachers and Jewish scholars. He was introduced into the printing business as an employee in his father's plant in Vienna, Austra. Already when he was 15 years of age, he was intrumental in helping to set up an edition of the Talmud. He became the youngest publisher in Vienna. Eventually, the firm of Von Schmid & Bush became the largest Hebrew publishing house in the world.

In 1842 he initiated the "Jahrbuch fuer Israeliten", the first almanac by Jewish authors for a Jewish public. Together with I. S. Reggio he published the Hebrew-German "Bikkurei ha-Ittim ha-Hadashim" (one issue, Vienna, 1845), in which he emphasized the need to learn and use the Hebrew language.

Following the repression of the 1848 revolutions, Bush left the Austrian Empire and immigrated to the USA settling in New York in 1949. He founded a book store and publishred for three months "Israels Herald" (in German), the first American Jewish weekly.

Bush moved to St. Louis, where he opened a general store in partnership with his brother-in-law, Charles Taussig, and began to prosper. In 1857 founded the People's Savings Bank, and served as its president until 1863.

During the American Civil War, Bush was appointed aide to Unionist General John C. Frémont in 1861, serving with the rank of captain until 1862. Bush was named general agent of the St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad and held that position until 1868. In 1864 he was one of the St. Louis delegates to the Missouri Constitutional Convention, and served as a member of the State Board of Immigration from 1865 to 1877.

During the later years of his life he won wide recognition as a viticulturist, planting vineyards in Bushberg, in Jefferson County MO, a large tract of land on the immediate outskirts of St, Louis that he purchased in 1851. He published the Bushberg Catalogue, a manual on grape-growing that later on was translated into many languages. In 1870, Isador Bush created the firm of Isidor Bush & Co. – a wine and liquor business.

Bush was one of the founders of B'nei El Temple, in St. Louis, and of the Cleveland Orphan Asylum (1868). In 1873 he was elected grand president of the St. Louis lodge of the B'nai B'rith. Bush was an active member and vice-president (1882) of the Missouri Historical Society.

Bush died in St. Louis in 1898.

Gabor (Gabriel) Szego (1895-1985), mathematician, born in Kunhegyes, Hungary (then part of Austria-Hungary). He studied at the Universities of Budapest, Berlin, Goettingen and Vienna, the latter bestowing upon him a PhD degree in 1918.

He was lecturer on Mathematics at the University of Berlin from 1921 onwards; in 1925 he was named associate professor. From 1926 to 1934 he was full professor of mathematics at the University of Koenigsberg, Germany (now Kaliningrad, Russia). In 1934 Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, invited him to occupy its chair of mathematics. From 1938 on he was professor of mathematics at Stanford University, where he helped build up the department until his retirement in 1966.

In addition to numerous memoranda to the mathematical press, Szego published a German version of A. G. Webster's "Partial Differential Equations" ("Partielle Differncialgleichungen der mathematischen Physik"; 1930) and "Aufgaben und Lehrsaatze aus der Analysis" (with G. Polya, 2 vol., 1925).

Szego died in Palo Alto, California.

Rita Levi-Montalcini (1909-2012), neurologist , 1986 Nobel prize laureate for medecine, born in Torino, Italy. She studied at the University of Torino and after graduation continued to work there. In 1939, following the Fascist racial legislation, she was forced to leave. She continued her research in an improvised laboratory at home the results of which were published in Belgium. In 1947 she moved to Washington University in St. Louis, USA, where she worked with Prof. Victor Hamburger. In 1977 she returned to Italy and was nominated head of the Laboratory for Cell Biology at the National Council for Scientific Research in Rome. In 1986 she was awarded the Nobel Prize for her dicovery of the NGF.

Ferdinand Isserman (1898-1972), Reform rabbi, born in Belgium, who immigrated to the United States with his family in 1906 and settled in Newark, New Jersey. He graduated from Central High School in Newark and then enrolled at Cincinnati's Hebrew Union College in 1914. While a rabbinic student at HUC, Isserman also attended the University of Cincinnati. He played on the university basketball team.

In 1922, Isserman was ordained as a rabbi and became an assistant rabbi in Philadelphia. He then moved to Toronto, Canada, in 1925 to become the rabbi at Toronto Hebrew Congregation. While in Toronto, Isserman arranged Canada’s first pulpit exchange between a rabbi and a Christian minister. In 1929, he became the rabbi of Temple Israel in St. Louis, USA, and retained the position until 1963. During his tenure at Temple Israel, Isserman was one of the most prominent rabbis in the United States.

In 1932, Isserman gave the opening prayer at the Republican National Convention, which nominated incumbent President Herbert Hoover. Prior to World War II, Isserman took three fact-finding missions to Nazi Germany (in 1933, 1935, and 1937), and learned of the existence of concentration camps. Upon his return to the United States, Isserman warned Americans of the evils of Nazism, but few people believed that the camps indeed existed. During World War II he served with the American Red Cross.

During his career, Isserman encouraged interfaith understanding and Jewish involvement in the Civil Rights Movement. For some years he was vice-chairman of the National Conference of Christians and Jews.

Joseph Pulitzer (1847-1911), editor and publisher, born in Mako, Hungary (then part of the Austrian Empire), the son of a Jewish father and a Roman Catholic mother. He immigrated to the United States at the age of 17 to serve in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Discharged from the cavalry in 1865, he went to St. Louis, MO, studied law and was admitted to the bar of Missouri.

In 1868 became a reporter for the German-language daily Westliche Post. Three years later he bought an interest in the paper, became managing editor, and sold back his shares at a vast profit. He bought declining newspapers and restored them to national influence. In 1878 Pulitzer took his first big step toward creating a newspaper empire when he bought The St. Louis Dispatch at an auction for $ 2,500 and merged it with The St. Louis Post into The Post-Dispatch. By 1881 it was yielding profits of $ 85,000 a year. He left for New York 1883 and bought The World from Jay Gould, the financier, for $ 346,000. Three years later, revived by Pulitzer's innovations in mass appeal journalism, The World was earning more than $ 500,000 a year. He established a sister paper in New York, The Evevning World, in 1887. All three newspapers succeeded on a formula of vigorous promotion, sensationalism, sympathy with labor and underdog, and innovations in illustration and typography.

Pulitzer was active in politics. From 1869 to 1871 he served in the Missouri legislature, and was elected as a Democrat to Congress from New York in 1885, but resigned in April 1886. He was also active in philanthropy. A man of intellect and energy, he worked himself into a condition which compelled to live his last years as a totally blind invalid. However, he still directed his newspapers. He endowed the Pulitzer School of Journalism at Columbia University and the famous Pulitzer Prizes for journalism.

His son, Joseph Jr. (1885-1957), continued the policies of his father with success as the publisher of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, but under his other two sons, Ralph and Herbert, the two New York papers declined and were sold in 1931 to Scripps-Howard. Pulitzer died at Charlston Harbor, SC, in 1911.

Saul Zaentz (1921-2013), an independent film producer who adapted literary works for the screen and won best-picture Academy Awards for “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “Amadeus” and “The English Patient”, born in Passaic, New Jersey USA, one of five children of Morris and Goldie Zaentz, Jewish refugees from a shtetl in eastern Poland.

Zaentz ran away from home at 15, sold peanuts at ballgames in St. Louis, made a little money gambling and traveled around the USA, hitchhiking and riding freight trains. He enlisted in the army in World War II and served in Africa, Europe and the Pacific. After the war he studied at Rutgers University, worked on a chicken farm and took a business course in St. Louis. He settled in San Francisco in 1950 and began working for a record distributor. In 1955 he was hired as a salesman by Fantasy Records, a label whose roster included the jazz pianist Dave Brubeck, the poet Allen Ginsberg and the comedian Lenny Bruce. He also managed tours for Duke Ellington, Stan Getz and others.

Zaentz was over 50 when he began making films, after having already made a fortune in the music business from the success of the rock group Creedence Clearwater Revival and the acquisition of a formidable jazz catalog. In a business driven by celebrity stars and box-office profits, he staked his reputation and his money on serious, intelligent films, often based on offbeat prizewinning books or plays, featuring rising stars and relatively untested directors passionate about the collaboration.

His major hits (each a decade apart), “Cuckoo’s Nest” (1975), “Amadeus” (1984) and “The English Patient” (1996), won 22 Oscars for his actors, actresses, directors and other contributors. And on Oscar night in 1997, Zaentz won the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award for lifetime achievement and his third best-picture award. It crowned a career and an evening of triumph, with nine Academy Awards conferred on “The English Patient”. Zaentz financed his own pictures when possible to retain creative control, selected his own stars and directors, and shot on location to capture the beauties of an African desert, a ruined Tuscan monastery or the jungles of Central America. Colleagues said he did not interfere with his artists’ work.

Bernard Illowy (1812-1871), rabbi, born in Kolin, he was ordained by Moshe Sofer in Pressburg (now Bratislava, Slovakia), studied Hebrew at the rabbinical school in Padua and got his doctorate at the University of Budapest. Fluent in various languages, he taught languages at the College of Znaim (Znojmo). In 1848 Illowy delivered revolutionary addresses to the forces passing through Kolin as a result of which he was deprived of rabbinic office and moved to the United States, where he was the only Orthodox rabbi with a doctorate. He served in New York, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Syracuse, Baltimore, New Orleans and Cincinnati. He strongly opposed the dominant Reform movement.

Vladimir Golschmann (1893-1972), conductor, born in Paris, France. In 1919 he founded the Golschmann Concerts, which he conducted for several years. He concentrated on contemporary French composers: Honegger, Milhaud, Poulenc and others. During the 1920s he was guest conductor of major orchestras both in Europe and America. In the early 1930s he was appointed conductor of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, a post he held for twenty-five years. Between 1958-1961 he was music director of the Tulsa Orchestra, and between 1964-1970 of the Denver Orchestra. He conducted two famous world premieres: George Antheil's Ballet mechanique in 1926, and Erich Wolfgang Korngold's Concerto for violin and orchestra in 1947. He died in New York.