The Ancient Synagogue of Sardis, Turkey

Haim F. Ghiuzeli

The ruins of the ancient city of Sardis (also spelled Sardes) lie near the modern village of Sart (also called Sartmahmut), about 10 kilometers west of the modern town of Sahlihli and some 70 kilometers east from Izmir (formerly Smyrna) in Western Anatolia (Asia Minor), now in Turkey. This former capital city of the antique Kingdom of Lydia (7th century BCE), is remembered today as the place where silver and gold coins were minted for the first time and as the city of the legendary rich king Croesus (560 – c.546 BCE). During its long history, Sardis changed many foreign rulers until its incorporation into the Roman Empire in 133 BCE. The city served then as the administrative center of the Roman province of Lydia. Sardis was reconstructed after the catastrophic earthquake of 17 CE and enjoyed a long period of prosperity under the Roman rule and then within the Byzantine Empire, until it was finally destroyed by the Mongols in 1402.

The beginnings of the Jewish settlement in Sardis are believed to belong to the 3rd century BCE, when Jews from Babylonia and other countries were encouraged to settle in the city by the Seleucid King Antiochus III (223-187 BCE). The Jews of Sardis are mentioned by Josephus Flavius in the 1st century CE, who refers to a decree of the Roman proquestor Lucius Antonius from the previous century (50-49 BCE): “Lucius Antonius, the son of Marcus, vice-quaestor, and vice-praetor, to the magistrates, senate, and people of the Sardians, sends greetings. Those Jews that are our fellow citizens of Rome came to me, and demonstrated that they had an assembly of their own, according to the laws of their forefathers, and this from the beginning, as also a place of their own, wherein they determined their suits and controversies with one another. Upon their petition therefore to me, that these might be lawful for them, I gave order that their privileges be preserved, and they be permitted to do accordingly.”1 (Ant., XIV:10, 17). It is generally understood that “a place of their own” refers to the synagogue serving the local Jewish community of Sardis. Josephus Flavius also mentions the decree of Caius Norbanus Flaccus, a Roman proconsul during the reign of Augustus at the end of the 1st century BCE, who confirms the religious rights of the Jews of Sardis, including the right to send money to the Temple of Jerusalem. (Ant., XVI:6,6).

The ruins of the Synagogue of Sardis were discovered in 1962 during archaeological excavations conducted by the Harvard-Cornell Sardis Expedition. The unearthing of the ruins under the supervision of the American archaeologists continued for another nine years. The dimensions of the building, its many decorations, including mosaics on the floors, marbling of the walls, various pieces of ritual furnishings and especially the over eighty inscriptions including six fragments in Hebrew and the rest in Greek that have been found in the interior, have contributed to the reputation of the site. The Synagogue of Sardis has since its discovery been acclaimed as the most outstanding Jewish monument from Antiquity unearthed in the entire region of Asia Minor and the Aegean Sea.

The building of the synagogue was situated at a central location in the city and apparently was an integral part of a complex that also included a gymnasium, some shops, and the public bath. The proximity of those public edifices to the synagogue led to two possible interpretations about the character of the local Jewish community. On one hand it has been assumed that the building was converted into a synagogue at a later date following its acquisition by the Jewish community, while according to the other view the inclusion of the synagogue within a public space along with the many Greek inscriptions should be understood as an expression of the Hellenistic nature of local Judaism. Moreover, the synagogue was not located within the Jewish quarter of the city, but stood on the main commercial thoroughfare of Sardis.

Since its discovery in the early 1960’s, the common accepted assumption among the researches considered the synagogue as belonging to the fourth century CE. The dating was based mainly on the discovery of a number of coins from the 3rd and 4th century CE beneath the mosaic floors. However, more recent research (Magness 2005), based on a reconsideration and new analysis of the original findings and the discovery beneath the floors of numismatic evidence from the early Byzantine period, suggest a later date for the building of the synagogue, most probably in the 6th century CE. Another hypothesis suggests that the building was used as a worship place by the Jews already from the 3rd or 4th century, but it acquired the current mosaic floors sometime during the 6th century, following several renovations of the edifice.

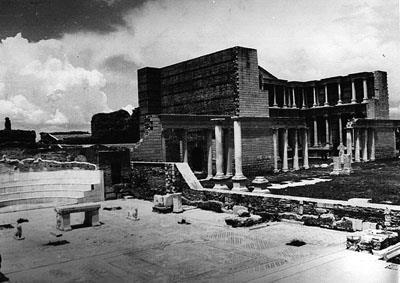

The structure of the Synagogue of Sardis recalls a typical Roman basilica. It is an impressive rectangular structure of 120 meters long and 18 meters wide on an east to west axis, between the palestra of the Gymnasium and the public road. It had a capacity of approximately 1000 persons, a hint to both the number of the Jewish population of the city and its economic and political status.

The building boasts a long central hall flanked by two rows of columns. Archaeological evidence suggests that the hall was created at a later date by the merging of three smaller rooms that used to be an integral part of the Bath and Gymnasium complex erected as early as the 1st century CE, during the construction period that followed the powerful earthquake of 17 CE. The remodeling of the complex and the creation of the long hall occurred sometime during the late 1st century and early 2nd century CE, most probably in order to adapt the structure to the functions of a civic center. It was only towards the end of the 3rd century or early 4th century that the building was occupied by the Jewish community. Converting the building into a synagogue led to some alterations to the original plan of the edifice, most notably the blocking of the only remaining doorway between the hall and the Gymnasium, thus ensuring a total separation of the Jewish religious activities from the pagan worship conducted in the other buildings of the complex.

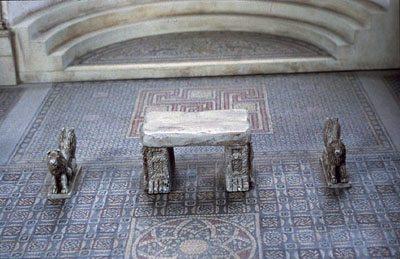

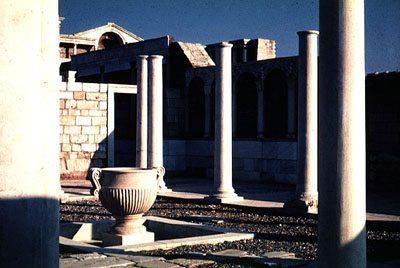

The entrance was located at the east end and the hall ended with and apse and three rows of curved stepped benches situated at the west end. It is believed that those seats were reserved for the elders of the community. A marble table with two eagles bas-reliefs on the outer sides of its legs along with two sculptures of lions standing on both lateral sides of the table has been preserved in front of the apse and probably served as the bimah of the synagogue. The decoration had a double symbolism: the eagle was a known Roman symbol while the lions were frequently used in the local art of Lydia, a region that in Antiquity was renowned for the wild lions that still roared its countryside. On the other hand both animals expressed also a strong Jewish symbolism, especially the lion, a common motif of Jewish art of the epoch that had long been emblematically associated with the Tribe of Judah and the city of Jerusalem. The overall length of the interior hall was shortened at a later stage with the east end redesigned by the addition of two shrines on both sides of the central door. These niches, one built in the Doric style and the other one in late Corinthian style, apparently served for sheltering the Torah scrolls, a practice found also in the synagogue of Ostia (a port town near Rome) and other antique synagogues. A forecourt with a central fountain was built at the east end of the hall and was linked to the main hall by three doorways.

View from the East End of the Interior Hall towards the Courtyard of the Synagogue of Sardis. Model. The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU – Museum of the Jewish People

The Table and the Statues of the Two Lions at the West End of the Interior Hall of the Synagogue of Sardis. Model. The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU – Museum of the Jewish People

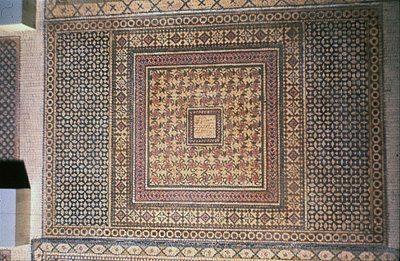

The floor mosaics cover both the main hall and the forecourt and have geometric, floral and animal decorations. The remaining portions of the walls are covered by colored marbles. The Greek inscriptions commemorate the names of various community members, its benefactors and their wives, both Jews and God-fearers, i.e. non-Jewish adherents of the synagogue. Some donors are listed as goldsmiths while others held various positions in the Roman civic administration of the city – the inscriptions mention a “count” and a former “procurator” among those who made financial contributions to the synagogue. One inscription mentions the vow of Samoe, an individual described as “priest and teacher of wisdom”.

Adjacent to the long southern wall of the synagogue and facing the main road, there was during Byzantine times a long row of shops, some owned by Jewish merchants others belonging to Christian traders, as indicated by a number of crosses found among the ruins.

The building of the Synagogue of Sardis was destroyed in 616, when the city was captured by the Sassanian Persians. It was never rebuilt and the Jewish community of Sardis ceased to exist.

The restoration of the synagogue started in 1965. The current appearance of the ruins attempts to reflect the way the synagogue looked like during the last years before its destruction.

Notes

1. Josephus Flavius. Antiquities of the Jews. English Translation by William Whiston.

Bibliography

CROSS, Frank Moore. The Hebrew inscriptions from Sardis Harvard Theological Review, 95,1 (2002) 3-19

KROLL, John H.. The Greek inscriptions of the Sardis synagogue. Harvard Theological Review, 94,1 (2001) 5-127

MAGNESS, Jodi. The Date of the Sardis Synagogue in Light of the Numismatic Evidence. American Journal of Archeology, 109:3 (July 2005): 443-475

SEAGER, Andrew R. The Building History of the Sardis Synagogue. American Journal of Archeology, 76 (1972):425-35