The Central Synagogue in Aleppo, Syria

Haim F. Ghiuzeli

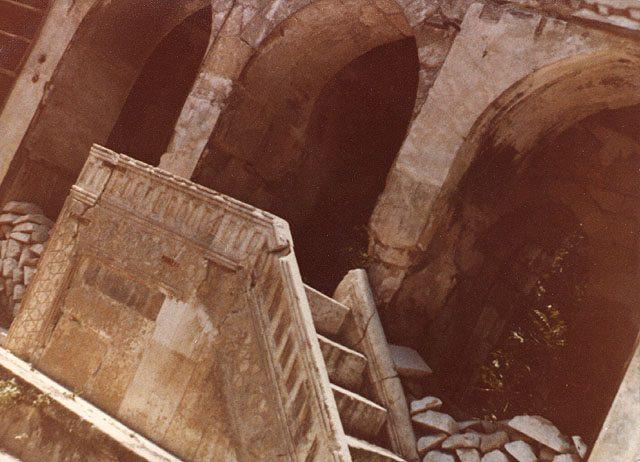

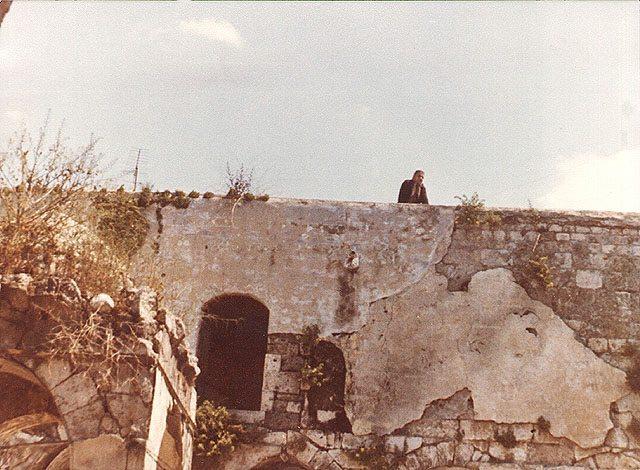

There was a Jewish place of worship on the site of the Aleppo Synagogue since late Antiquity, perhaps from as early as the 5th century C.E. The oldest surviving inscription is from the year 834 C.E. These early buildings were damaged after the Mongol occupation of Aleppo during the 13th century and then turned into a mosque. The central synagogue was rebuilt at some point in the early 15th century. It had later on undergone a series of modifications until its destruction during the violent attacks against Jews by the local population in December 1947.

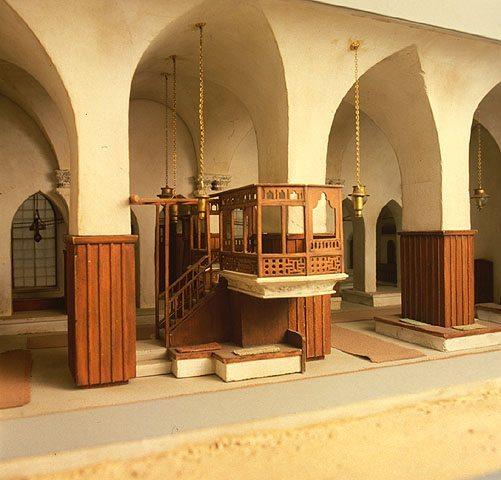

Apparently the Aleppo Synagogue included from the very beginning an adjacent courtyard that was used as an open-air synagogue in the summertime. Some hints in the Talmud suggest that it was customary for a synagogue to have its roof removed during the summer (Baba Batra, 3, p.2) and indeed in several places Jews preferred to pray in outdoors places, like Rabbi Asi and Rabbi Ami who prayed “among the columns” in Tiberias (Berachot, 8, pp1-2). Synagogues in Baghdad, Iraq, did not have a roof either, except over the Holy Ark and the tevah (elevated platform).

The Aleppo Synagogue edifice was divided into three main sections: a central courtyard that separated the western wing, where in modern times the “mustarabi” community used to worship, from the eastern section built at a later time during the 16th century and which served as Beth Midrash and prayer hall of the “Francos”, i.e. Sephardi Jews that settled in the town after the Spanish exile and other European Jews that happened to sojourn in Aleppo. An additional enclosed small courtyard was bordering the eastern wing farther to the east.

The western hall had three heichaloth (Holy Arks); there were another three heichaloth on the southern wall (“the Zion Wall”) of the courtyard, and a seventh Holy Ark, located in the eastern wing close to the courtyard, also on the southern wall pointing to the direction of Jerusalem that was named Heichal Eliyahu or Me’arat Eliyahu (“The Cave of Eliyahu”) and in which the old Torah and Bible manuscripts – the Ketarim (“Crowns”) also called the Taj by the Aleppo Jews were kept.

The “Jewel” of the Crowns” is the Hebrew manuscript of the Bible written by the scribe Shlomo Ben Buya’a during the first half of the 10th century (or 896?) and then verified, vocalized and pointed by Aaron Ben-Asher in Tiberias. It was taken to Egypt where it was seen by Maimonides, who considered it to be the most perfect of all versions and used it as an example and standard of the Bible text. Sometime towards the end of the 14th century the manuscript was taken into the custody of the Jewish community of Aleppo. Keter Aram Tzova (The Aleppo Codex), the most authoritative manuscript of the Masoretic text of the Bible, was kept in the Central Synagogue of Aleppo for some 500 years until 1947. Apparently it was damaged in the fire of the synagogue in 1947, and thought to be lost until 1958, when it was brought to Israel. Now most of its pages, 295 of the original 487, are safeguarded in Jerusalem, Israel.