The Remuh Synagogue of Krakow, Poland

The Remuh Synagogue is named after Rabbi Moshe Isserles (c.1525-1572), known by the Hebrew acronym REMA (pronounced REMU in Yiddish), the famous author of Ha-Mappah (literally “The Tablecloth”), a collection of commentaries and additions that complement Rabbi Josef Caro’s Shulhan Arukh with Ashkenazi traditions and customs. According to one popular tradition, Israel (Isserl) ben Josef, the grandson son of Moshe Auerbach of Regensburg founded the synagogue in honor of his son Moshe Isserles, who already in his youth was famed for his erudition. Following other tradition, the synagogue was founded by Rabbi Moshe Isserles in memory of Golda, his first wife who passed away at the age of twenty. However, the Hebrew inscription of the foundation tablet reads: “Husband, Reb Israel, son of Josef of blessed memory, bound in strength, to the glory of the Eternal One, and of his wife Malka, daughter of Eleazar, let her soul be received among the living, built this synagogue, the house of the Lord, from her bequest. Lord restore the treasure of Israel”, meaning that the synagogue was built in memory of Malka, the wife of Israel ben Josef. It should be pointed out that Israel ben Josef was a wealthy banker who settled in Krakow only in 1519, following the expulsion of Jews from the German city of Regensburg.

The Remuh Synagogue was built in Kazimierz (also known as Kushmir by Jews), now a district of Krakow, an area located on the bank of the Vistula River, immediately to the south of the Royal Castle on the Wawel Hill. Kazimierz had a Jewish community since the 14th century, and after the end of the 15th century when the Jews of Krakow were expelled from the city, it became the main Jewish neighborhood in the region and one of the largest Jewish communities in Poland. Originally called the “New Synagogue” to distinguish it from the Old Synagogue (Stara Boznica, in Polish) the Remuh Synagogue was built in 1553 at the edge of a newly established Jewish cemetery (today known as the Old Cemetery) on land owned by Israel ben Josef. This date is stated clearly on the foundation tablet. Nevertheless, the royal permission by King Sigismund II Augustus was obtained in November 1556, after long opposition from the Church. As it is hard to believe that the construction actually began without the royal permission, therefore the inscription should be understood as possibly referring to the date when the decision to build a second synagogue in Kazimierz was taken by its founder. The year 1552 must have been a terrible time for the family of Israel ben Isserles: his mother, wife, and daughter-in- law, the first wife of Rabbi Moshe Isserles, and probably other family members died in the epidemic that hit Krakow that year, in addition to numerous Jewish inhabitants of Kazimierz. The first building of the synagogue, probably a wooden structure, was destroyed in a fire in April 1557, but following a new permission granted by King Sigismund II Augustus of Poland, a second building of masonry was erected in place in 1557 after the plans of Stanislaw Baranek, a Krakow architect.

The original late Renaissance style edifice underwent a number of changes during the 17th and the 18th centuries. The current building traces its design to the restoration work of 1829, to which some technical improvements were introduced during the restoration of 1933 conducted under the supervision of the architect Herman Gutman. During the Holocaust, the synagogue was sequestered by the German Trust Office (Treuhandstelle) and served as a storehouse of firefighting equipment, having been despoiled of its valuable ceremonial objects and historic furbishing, including the bimah. However, the building itself was not destroyed. In 1957, thanks to the efforts of the local Jewish community and of Akiba Kahane, the Joint representative in Poland, the Remuh Synagogue underwent a major restoration that reestablished much of the prewar appearance of the interior.

The entrance to the synagogue courtyard is located at 40 Szeroka St. (in the past also known as the Main Street) at the heart of the historic Jewish quarter of Kazimierz. Above the gate is an arch with the Hebrew inscription: “The New Synagogue Dedicated to the Blessed Memory of Rabbi Remu”. The courtyard walls carry inscriptions in memory of the Jews of Krakow who perished in the Holocaust. The main room of the synagogue is accessed through a small entrance hall on the north side of the building next to a separate entrance to the women’s section. It has white painted limestone walls with large round headed windows in the north and south sides and lunettes on the east and west sides. A number of chandeliers, some standing, and others hanging from the ceiling contribute to the bright and airy atmosphere of the interior. The prayer hall features a centrally situated rectangular bimah with a reconstructed wrought-iron enclosure that has two entrances, one displaying an 18th century polychrome double door coming from a destroyed synagogue outside Krakow. The bimah door is decorated with a crowned menorah in gilded bas-reliefs whose style appears to have been inspired by the popular art of the region. The late Renaissance style Holy Ark has an Art Nouveau door, above which there are Hebrew inscriptions from the Bible. A candle (ner tamid) with the Hebrew inscription “An eternal flame for the soul of Remu, a man of blessed memory” is situated at the left side of the Holy Ark, while at its right a reconstructed plaque commemorates the place where Rabbi Moshe Isserles used to pray. One of the chairs on the eastern wall is reserved in his honor. The foundation tablet has been preserved near the southern wall. A clock presented by Chaim Herzog, the sixth President of Israel during his visit to the synagogue in 1992 is one of the latest additions to the otherwise simple furbishing. The women’s section was originally located on the first floor of a wooden structure connected to the northern wall of the synagogue. It has since undergone major restorations and the present women’s gallery is adjacent to the northern wall of the praying hall.

The Remuh synagogue, the smallest of all historic synagogues of Kazimierz, currently functions as a place of worship serving the tiny Jewish community of Krakow and the many Jewish visitors to the city.

The old Jewish cemetery of Krakow is located just behind the Remuh synagogue and is an integral part of a unique historical complex. The inscription above the current gate, moved from its previous location at the original gate on the Jakuba St., testifies that the cemetery was founded in 1552, being one of the earliest extant in Poland. The Old Cemetery served as the main burial place for the Jews of Krakow until 1800, although some prominent Jews were buried there after that date. In 1845, at the intervention of Rabbi Dov Beer Meisels (1798-1870), who emphasized the historic and spiritual importance of the cemetery, the authorities of the City of Krakow cancelled a town-planning scheme that could have led to the destruction of the graveyard. However, the cemetery fell in decay and in the 1940s, the Nazis brought about almost total ruin. Only about a dozen tombstones survived the Holocaust destruction, among them the graves of Rabbi Moshe Isserles and his family.

During the late 1940s and the 1950s, hundreds of old tombstones were uncovered by archeological excavations conducted on the grounds of the cemetery. Some of the tombstones are thought to have been deliberately buried in order to escape devastation by the invading Swedish troops in 1704. Hundreds of fragments were fixed on the inner side of the cemetery wall along Szeroka St. It soon became known as the Wailing Wall serving as a memorial to the destroyed Jewish community of Krakow. Some of the recovered tombstones belong to illustrious rabbis and members of the Jewish community of Krakow, among them the most venerated is that of Rabbi Moshe Isserles. His tombstone is covered with lots of notes with requests from pilgrims coming from all over the world.

Members of the Isserles family and other illustrious Jews buried in the Old Cemetery of Krakow:

-

Rabbi Moshe Isserles, known as REMU (c.1525-1572)

-

Israel ben Josef (d.1568), father of Rabbi Moshe Isserles, a merchant, and banker

-

Malka (d.1552), mother of Rabbi Moshe Isserles

-

Golda (d.1552), daughter of Rabbi Shalom Shachna of Lublin and the first wife of Rabbi Moshe Isserles

-

Gitel (d.1552), daughter of Moshe Auerbach of Regensburg

-

Miriam Bella (d.1617), sister of Rabbi Moshe Isserles

-

Yitzhak (d. after 1885), known as Yitzhak the Rich, brother of Rabbi Moshe Isserles, a merchant and banker

-

Drezel (d. before 1560), daughter of Rabbi Moshe Isserles and wife of Simcha Bunem Meisels

-

Yitzhak Jakubowicz (d.1653)

Merchant, banker, and leader of the Jewish community of Krakow during the first half of the 17th century, founder of the Izaak Synagogue in Kazimierz.

-

Mordechai Margulies (d.1617)

Head of the Krakow yeshiva from 1591 to 1617

-

Shmuel bar Meshulam (d.1552)

Physician to the Polish kings Sigismund I “The Old” (1506-1548) and Sigismund II Augustus (1548-1572)

-

Joel Sirkis (1561-1640)

Known as BACH, chief rabbi of Krakow from 1618 until 1640 and head of the local yeshiva

-

Eliezer Ashkenazi (1512-1585)

Son of Eliahu, he was rabbi in Cairo, Egypt, in Famagusta, Cyprus, and in Poznan, Poland, before settling in Krakow

-

Yitzhak Landau (d.1768)

Chief rabbi of Krakow from 1754 until 1768

-

Gershon Saul Yomtov Lipman Heller (1579-1654)

Son of Nathan, a rabbi in Vienna, then in Prague and a number of small towns in Poland, he was chief rabbi of Krakow and head of the local Yeshiva.

Address:

The Remuh Synagogue and Cemetery

40 Szeroka St.

Kazimierz

Krakow

Poland

Burial place of Rabbi Moshe Isserles and his family, Krakow, 1970s. The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People

Tombstone of Rabbi Gershon Saul Yomtov Lipman Heller. The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People

Holy Ark of the Remuh Synagogue, 1973. The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. Courtesy Tadeusz Kowalski, Poland

Doors of the bimah in the Remuh Synagogue, 1979. The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. Courtesy Isaiah Weinberg, Israel

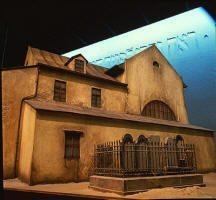

Southern façade of the Remuh Synagogue with the tombstones of the family of Moshe Isserles. Model, The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People

Entrance to the Remuh Synagogue. Model, The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People

Interior view of the Remuh Synagogue. Postcard, 1920’s. Photo album by Bnai Brith, Krakow. The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People