The Jewish Community of Istanbul

Istanbul

Until 1453 Constantinople (Kushta, Costandina, Costantina).

City in Turkey, on both sides of the Bosporus at its entrance on the sea of Marmara.

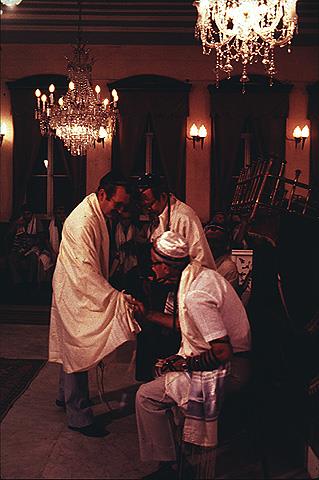

There were 1,743,000 inhabitants in 1965 and 20,000 Jews in 1976, with a general community council comprising 60 men, including some of the Ashkenazi community. It elects the head of the community, administration, and religious committees. The chief rabbi was officially recognized in 1953. The community organized the Or-Chayyim hospital (built 1885), an orphanage, the "tzedakah u-marpe" charitable organization (founded 1918) for underprivileged students, "machzikei torah" for training cantors and mohalim, and an old age home. The community had three elementary schools and a high school, the 1,000 students being mainly poor - wealthy children attended foreign schools. Among the youth groups were "Kardeslik" and "Amical" which provided some Hebrew education. The level of education improved under the Alliance Israelite Universelle. Jews were well represented in commerce but very few were in the civil service.

In the Byzantine period, the Jewish area changed five times, and in the Turkish invasion, 1453. Jews worked in copper, tanning, dyeing, silk weaving, and - despite church opposition - Jewish doctors served at court. In the 11th and 12th centuries Jews were compelled to work as executioners. They were politically active in the circus parties, the blues and greens. Leo III gave the Jews the choice of leaving the town or being baptized (721), but the community continued to exist, as shown by the poet Shephatiah Ben Amittai, Benjamin of Tudela, and Judah Aharizi. Messianic fervor arose due to the first crusade (1095-1099). Many Jews were killed in riots against western merchants at the end of the 12th century. An important Karaite community of Jews from Venice and Genoa existed from the 11th century until the Turkish conquest.

With the Ottoman conquest the armies of Muhammad II totally massacred the inhabitants of Istanbul except the Jews, seemingly because of their support. Muhammad II brought residents of Anatolia and the Balkans to repopulate Istanbul - among them Jews and Karaites engaged as craftsmen and the Romanids (Gregos), formerly of Greece and Byzantium, Ashkenazim, Italians, and Sephardim. The Jews of Istanbul, as in all the Ottoman Empire, constituted an autonomous religious-administrative unit, first led by rabbi Moses Capsali, who represented the community before the government and collected the Jewish taxes; after him was rabbi Elijah Mizrachi. The Ashkenazim from Bavaria and Hungary enjoyed an independent status for many years and among its distinguished personalities were Elijah Ha-Levi Ha-Zaken, and the court physician Solomon Tedesci. Relations continued with their countries of origin but in time they assimilated with the Sephardim. When Jews from Spain and Portugal settled in Istanbul ( approximately 40,000 from Spain) they included rabbis, judges, and heads of yeshivot including Joseph Ibn Lev, Joseph Taitatzak, Abraham Jerusalmi, rabbi Isaac Caro, and rabbi Elijah Ben Chayyim. They founded large yeshivot which raised the spiritual and cultural level of local Jewry. Their financial status and numerical superiority gave them a prestigious place in the community.

The Sultans appreciated the Jewish contribution to commercial life, crafts, medicine, and the manufacture of firearms, and 16th century Istanbul was one of the world's most important Jewish centers. Among notables in the community were the family of doctors Hamon, and prominent bankers and capitalists, holders of central financial positions in the empire whose position in court was beneficial to the rest of the community; for example, the Mendes family from Portugal, his widow Gracia and her nephew Don Joseph Nasi who rebuilt Tiberias, and the families of Solomon Ibn Ya'ish and Jacob Ankawa. The magnificence and exhibitionism of wealthy Jews angered the inhabitants who forbade lavish clothing and jewelry. As the Ottoman Empire declined culturally and economically, so did the Jewish community. When a number of Jewish quarters were destroyed by fire the structure of the "Kehalim" changed. During the reign of Murad IV Jews were accused of murdering a Turkish child for ritual purposes (1633). Many Jews were captured by the Cossacks, Turks, and Ukrainians in the massacres of 1648-49, and sold as slaves in Istanbul where local Jewry redeemed them at great expense. In 1666 Shabbetai Tzevi arrived in Istanbul and many followed him. His opponents had him arrested and with the movement's failure the Jewish community declined. Great fires destroyed the Jewish quarters in the 17th and 18th centuries - the greatest in 1740 - after which the Jews, forbidden to rebuild, moved to other areas of the town. At this time the "treasurers for Israel" were active, collecting contributions for the inhabitants of Eretz Israel. In 1727 a weekly tax was imposed for the benefit of Jerusalem - obliging all Jews in the empire and Italy. The money went for the upkeep of the holy cities of Israel.

Until the end of the 18th century Istanbul was a major center for Hebrew publishing.

In the 18th and 19th centuries the standard of Hebrew learning reached such a low point that the majority could not read the bible. Books were published in Spanish and Ladino. Among the great writers were rabbi Jacob Culi of Safed, author of Ma'am Loas, who settled in Istanbul in the mid- 18th century, and rabbi Abraham Ben Isaac Assa, "the father of Ladino literature", who translated the bible, religious works, science, and the Shulchan Arukh. Distinguished families included the Kimitti, Rosanes, and Navon families. rabbi Chayyim Kimchi headed a yeshivah, and rabbi Judah Rosens published against the Shabbatean movement. Isaiah Adsiman, Bekhor Isaac Carmona, Ezekiel Gabbai, and Abraham de Camondo, all men of great power, were influential in government circles in the 19th century. De Camondo founded a modern school and guaranteed half its expenses. A "va'ad perkidim" was founded, composed of wealthy men and progressive intellectuals. Splits occurred between the latter and the conservatives led by the Chakham Bashi (chief rabbi). During the reign of Abdu-l-Mejid I (1839- 61), Jews were accepted into the military school of medicine and poll tax was abolished. The secular leadership strengthened, and in the days of the Sultan Abul Zziz, the Jews published chief rabbi, a secular council containing Jewish government officials, and a rabbinical council. The two councils were elected for three years. Each quarter had a local rabbi with a secretary whose duty it was to send reports of births and deaths to the government. Three Battei Din dealt with matrimonial matters, and other affairs went before a municipal tribunal. These ordinances remained in effect until the establishment of the republic in 1923. In the second half of the 19th century Jews received decorations and held high government administrative posts. Newspapers and periodicals began to appear in Ladino (the first, Or Israel, was edited by Chayyim de Castro in 1853). Jewish population grew to 100,000 at the start of the 20th century due to Russian emigration from the 1905 revolution.

With the establishment of the republic the community was forbidden to levy its own taxes and personal status came under civil jurisdiction. Turkish replaced French as the language of instruction (used in Alliance schools throughout the Middle East and North Africa) and affiliation with foreign organizations, such as the World Jewish Congress and the World Zionist Organization, was prohibited. In 1932 all schools were secularized and religious education forbidden. Like other non-Muslim subjects, the Jews of Istanbul were most severely affected by the imposition of the capital levy of 1942. Many of those who could not meet these levy payments were compelled to sell their property. In 1949 Jews received autonomy, proposed by Solomon Adato, a delegate in the house of representatives. Religious instruction was again permitted in public schools, and many young Jews went to universities. The number of Jews in Istanbul, estimated at 55,000 in 1948, dropped to 32,946 and 30,831 in the 1955 and 1965 censuses as a result of the large-scale emigration to the state of Israel. In 1970 an estimated 30,000 Jews lived in Balat, Haskoy, Ortakoy, and other quarters. The wealthy lived in the Pera and Sisli neighborhoods.

In 1997 there were 20,000 Jews living in Turkey; about 17,000 of them - in Istanbul.

Until 1453 Constantinople (Kushta, Costandina, Costantina).

City in Turkey, on both sides of the Bosporus at its entrance on the sea of Marmara.

There were 1,743,000 inhabitants in 1965 and 20,000 Jews in 1976, with a general community council comprising 60 men, including some of the Ashkenazi community. It elects the head of the community, administration, and religious committees. The chief rabbi was officially recognized in 1953. The community organized the Or-Chayyim hospital (built 1885), an orphanage, the "tzedakah u-marpe" charitable organization (founded 1918) for underprivileged students, "machzikei torah" for training cantors and mohalim, and an old age home. The community had three elementary schools and a high school, the 1,000 students being mainly poor - wealthy children attended foreign schools. Among the youth groups were "Kardeslik" and "Amical" which provided some Hebrew education. The level of education improved under the Alliance Israelite Universelle. Jews were well represented in commerce but very few were in the civil service.

In the Byzantine period, the Jewish area changed five times, and in the Turkish invasion, 1453. Jews worked in copper, tanning, dyeing, silk weaving, and - despite church opposition - Jewish doctors served at court. In the 11th and 12th centuries Jews were compelled to work as executioners. They were politically active in the circus parties, the blues and greens. Leo III gave the Jews the choice of leaving the town or being baptized (721), but the community continued to exist, as shown by the poet Shephatiah Ben Amittai, Benjamin of Tudela, and Judah Aharizi. Messianic fervor arose due to the first crusade (1095-1099). Many Jews were killed in riots against western merchants at the end of the 12th century. An important Karaite community of Jews from Venice and Genoa existed from the 11th century until the Turkish conquest.

With the Ottoman conquest the armies of Muhammad II totally massacred the inhabitants of Istanbul except the Jews, seemingly because of their support. Muhammad II brought residents of Anatolia and the Balkans to repopulate Istanbul - among them Jews and Karaites engaged as craftsmen and the Romanids (Gregos), formerly of Greece and Byzantium, Ashkenazim, Italians, and Sephardim. The Jews of Istanbul, as in all the Ottoman Empire, constituted an autonomous religious-administrative unit, first led by rabbi Moses Capsali, who represented the community before the government and collected the Jewish taxes; after him was rabbi Elijah Mizrachi. The Ashkenazim from Bavaria and Hungary enjoyed an independent status for many years and among its distinguished personalities were Elijah Ha-Levi Ha-Zaken, and the court physician Solomon Tedesci. Relations continued with their countries of origin but in time they assimilated with the Sephardim. When Jews from Spain and Portugal settled in Istanbul ( approximately 40,000 from Spain) they included rabbis, judges, and heads of yeshivot including Joseph Ibn Lev, Joseph Taitatzak, Abraham Jerusalmi, rabbi Isaac Caro, and rabbi Elijah Ben Chayyim. They founded large yeshivot which raised the spiritual and cultural level of local Jewry. Their financial status and numerical superiority gave them a prestigious place in the community.

The Sultans appreciated the Jewish contribution to commercial life, crafts, medicine, and the manufacture of firearms, and 16th century Istanbul was one of the world's most important Jewish centers. Among notables in the community were the family of doctors Hamon, and prominent bankers and capitalists, holders of central financial positions in the empire whose position in court was beneficial to the rest of the community; for example, the Mendes family from Portugal, his widow Gracia and her nephew Don Joseph Nasi who rebuilt Tiberias, and the families of Solomon Ibn Ya'ish and Jacob Ankawa. The magnificence and exhibitionism of wealthy Jews angered the inhabitants who forbade lavish clothing and jewelry. As the Ottoman Empire declined culturally and economically, so did the Jewish community. When a number of Jewish quarters were destroyed by fire the structure of the "Kehalim" changed. During the reign of Murad IV Jews were accused of murdering a Turkish child for ritual purposes (1633). Many Jews were captured by the Cossacks, Turks, and Ukrainians in the massacres of 1648-49, and sold as slaves in Istanbul where local Jewry redeemed them at great expense. In 1666 Shabbetai Tzevi arrived in Istanbul and many followed him. His opponents had him arrested and with the movement's failure the Jewish community declined. Great fires destroyed the Jewish quarters in the 17th and 18th centuries - the greatest in 1740 - after which the Jews, forbidden to rebuild, moved to other areas of the town. At this time the "treasurers for Israel" were active, collecting contributions for the inhabitants of Eretz Israel. In 1727 a weekly tax was imposed for the benefit of Jerusalem - obliging all Jews in the empire and Italy. The money went for the upkeep of the holy cities of Israel.

Until the end of the 18th century Istanbul was a major center for Hebrew publishing.

In the 18th and 19th centuries the standard of Hebrew learning reached such a low point that the majority could not read the bible. Books were published in Spanish and Ladino. Among the great writers were rabbi Jacob Culi of Safed, author of Ma'am Loas, who settled in Istanbul in the mid- 18th century, and rabbi Abraham Ben Isaac Assa, "the father of Ladino literature", who translated the bible, religious works, science, and the Shulchan Arukh. Distinguished families included the Kimitti, Rosanes, and Navon families. rabbi Chayyim Kimchi headed a yeshivah, and rabbi Judah Rosens published against the Shabbatean movement. Isaiah Adsiman, Bekhor Isaac Carmona, Ezekiel Gabbai, and Abraham de Camondo, all men of great power, were influential in government circles in the 19th century. De Camondo founded a modern school and guaranteed half its expenses. A "va'ad perkidim" was founded, composed of wealthy men and progressive intellectuals. Splits occurred between the latter and the conservatives led by the Chakham Bashi (chief rabbi). During the reign of Abdu-l-Mejid I (1839- 61), Jews were accepted into the military school of medicine and poll tax was abolished. The secular leadership strengthened, and in the days of the Sultan Abul Zziz, the Jews published chief rabbi, a secular council containing Jewish government officials, and a rabbinical council. The two councils were elected for three years. Each quarter had a local rabbi with a secretary whose duty it was to send reports of births and deaths to the government. Three Battei Din dealt with matrimonial matters, and other affairs went before a municipal tribunal. These ordinances remained in effect until the establishment of the republic in 1923. In the second half of the 19th century Jews received decorations and held high government administrative posts. Newspapers and periodicals began to appear in Ladino (the first, Or Israel, was edited by Chayyim de Castro in 1853). Jewish population grew to 100,000 at the start of the 20th century due to Russian emigration from the 1905 revolution.

With the establishment of the republic the community was forbidden to levy its own taxes and personal status came under civil jurisdiction. Turkish replaced French as the language of instruction (used in Alliance schools throughout the Middle East and North Africa) and affiliation with foreign organizations, such as the World Jewish Congress and the World Zionist Organization, was prohibited. In 1932 all schools were secularized and religious education forbidden. Like other non-Muslim subjects, the Jews of Istanbul were most severely affected by the imposition of the capital levy of 1942. Many of those who could not meet these levy payments were compelled to sell their property. In 1949 Jews received autonomy, proposed by Solomon Adato, a delegate in the house of representatives. Religious instruction was again permitted in public schools, and many young Jews went to universities. The number of Jews in Istanbul, estimated at 55,000 in 1948, dropped to 32,946 and 30,831 in the 1955 and 1965 censuses as a result of the large-scale emigration to the state of Israel. In 1970 an estimated 30,000 Jews lived in Balat, Haskoy, Ortakoy, and other quarters. The wealthy lived in the Pera and Sisli neighborhoods.

In 1997 there were 20,000 Jews living in Turkey; about 17,000 of them - in Istanbul.