The Jewish Community of Samara

Samara

Самара

A city in the Samara Oblast, southwestern Russia.

Early History

The city of Samara is situated on the lower Volga Region of European Russia. Between 1935-1991, the city was known as Kuibyshev. The territory of Samara came under the influence of the Khazar Khanate in the 7th century. It was crossed with major trade routes, which connected Khazaria with China. Khazar rule was brought to an end in the late 10th century when the troops of the Kievan prince Svyatoslav defeated the troops of Josef, the Khagan of Khazaria. The city of Samara was founded in 1568 in order to defend the southeastern borders of the Russian state from Nogay and Crimean Tatars. Samara is mentioned in official documents from 1586 during the reign of Fedor Ioannovich (1557-1598) who was responsible for the construction of a fortress on the Volga for protection from the Nogays and Kalmyks.

With the consolidation of the Russian state around Moscow, Samara's strategic significance declined. In 1688, Samara was recognized as the regional city and began to develop as a center of trade and commerce serving communities in the regions of central Russia and the Volga basin. During 17th -18th centuries, Samara served as shelter for the participants in the peasant revolts of Stepan Razin (c.1630-1671) and Yemelyan Pugachev (c.1742-1775). Following the abolition of serfdom in Russia (1861), Samara became a center of the agriculture and flour industries. The first railway that connected Siberia with the Ural region ran through Samara.

Early Jewish Settlement

Samara was located outside the Pale of Settlement1. Because of this Jews began to settle in the city only during the second half of the 19th century when the adoption of several laws made it possible for some categories of Jews to live outside the Pale of Settlement. Former Cantonists, young Jewish boys drafted by force to the Russian army, where among the first to be allowed to settle outside the bounders of the Pale, having completed 25 years of military service. According to the laws of 1859 and 1865, all categories of Jewish traders and craftsmen received permission to settle in cities outside the Pale of Settlement, with the exception of Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Only eight Jews (all males, possibly former Cantonists) lived in Samara by 1853. By 1862, the number had risen to 92 and the settlement continued in the following years. By 1871, there were 339 Jews and then 515 in 1878. Most of them were large traders, retired soldiers, artisans, and members of their families.

Jews were among the initiators and organizers of the Orenburg project that led to the laying of a railway connecting Samara with the central Russian guberniyas. In 1874, the first rabbi arrived in Samara. Two synagogues were opened in 1880 and 1887, but the official registration of the Jewish community of Samara was delayed until 1895. A little over 1300 Jews lived in Samara in 1897 representing 1.5% of the city population, and three years later, their numbers had grown to about 1550. Large Jewish traders began exporting agricultural products from the Samarskaya Guberniya. They also established the first beer factory, producing the Zhigulevskoe beer, a brand that is still famous today. The “Great Synagogue,” with a capacity of about 1,000 people, was built in Samara in 1908, and then in 1910 an institution of higher education for the members of the Jewish community was established with the financial support of a branch of the All- Russian society for the dissemination of education

among Russian Jews. An important role in the Jewish community of Samara was played Yaacov Teitel (1850-1939), a celebrated lawyer and by Benjamin Portugalov (1835-1936), a renowned doctor, journalist, and a distinguished member of the Jewish community.

Yaacov Teitel (1850–1939), graduated the gymnasium in Mozyr (now in Byelorussia) in 1871 and in 1875 completed his studies at Law School of the Moscow State University. As a student, he wanted to establish a national Jewish paper in Russian in order to fight the anti-Semitism in western and southwestern guberniyas of the Russian empire. From 1877, he served as an attorney at the regional court of Samara and was a member of the court administration. Nicknamed the “Happy Pious” in recognition of his generosity and philanthropy, he was awarded the title of “Complete State Counselor” in 1912, and retired from public life. In 1921, he emigrated to Berlin where he established the community of Russian Jews in Germany, and in 1933 he settled in France.

Benjamin Portugalov (1835-1936), was born in 1835 into a wealthy merchant family in Poltava (now in the Ukraine) and studied medicine at the universities of Kharkov and Kiev. Already during his early youth, he was involved into revolutionary activities. He was arrested several times and deported to Kazan where he lived under police supervision. He graduated the School of Medicine of Kazan University in 1860 and moved to Samara in 1871, where he lived until his death in 1936. His participation in philanthropic and educational activities in Samara included organizing a series of lectures on literature, history, and culture, held at the city theater, as part of “open educational program”. Dr. Portugalov initiated the establishment and development of the regional medical service for all residents. This was expanded to a regional school for training of medical assistants. A new method for treatment of alcoholism, which became a serious problem for the local Jewish community, was another

of his accomplishments. His views on the future of Jews of the Russian empire were completely opposite to those of Yaakov Teitel. Portugalov stood for the complete assimilation of Jews and fought the “old destructive beliefs” (sic) of the observant Jews on circumcision, ritual slaughter, and marriage.

Jewish Life during the Soviet Era

During World War I and the Russian Civil War, many Jewish refugees from the western regions of Russia settled in Samara fleeing the anti-Jewish violence. In 1926, the Jewish population of Samara was estimated at about 7,000 individuals representing 4% of the whole city population. During the 1920's the Bolshevik party and the Komsomol - the youth organization of the Communist party - held a campaign against religion, including Judaism. In 1929, the Great Synagogue was transformed into a House of Culture and later into a bread factory. The Yiddish language Jewish school that included a Drama school functioned until 1938.

During WWII thirty-nine important Soviet ministries and foreign embassies were relocated to Samara. Jewish life in Samara, during the war years, was closely connected to the activity of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC). The JAC was established in Samara in April 1942. The idea to organize the JAC was proposed by the head of NKVD- KGB, Lavrenti Beria (1899-1953). The organization was intended to serve the interests of Soviet foreign policy and the Soviet military through media propaganda, as well as through personal contacts with Jews abroad, especially in Britain and United States. The key personalities in the JAC were Henryk Erlich (Wolf Herch) (1882-1941), a journalist and a veteran member and one of the leaders of the Bund – the Jewish Socialist Party - in Poland, and Viktor Alter (1890-1941), a member of the executive committee of the Bund in Poland. Erlich, who in his earlier career was a member of the Executive Committee of the Petersburg Soviet from 1917, later

emigrated to Poland. In 1939, he was arrested and sent into prison by the Soviets, but was released in order to build and to organize the activity of JAC. Erlich was assisted in his work by Alter, who was a close friend of him, after Alter too was released from the prison. In Samara, they were in contact with foreign representatives, mostly Americans. They proposed to organize a special Jewish legion in the United States and deploy it on the Soviet-German front. Both men believed that they could change the Soviet political system and turn it into a more liberal regime. They were arrested again at the end of 1942 for “anti-Communist activity”. Erlich committed suicide at the city prison and Alter was executed later.

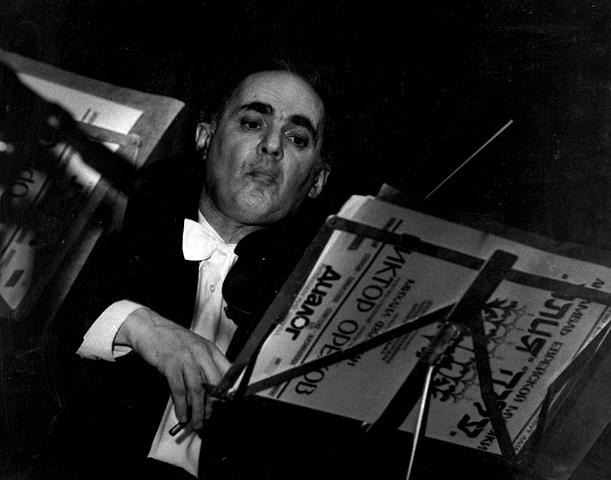

Solomon Mikhoels (1890-1948), a famous actor and director of the Moscow Yiddish State Theater was appointed as chairman of JAC. Shahne Epshtein, a Yiddish journalist, was the secretary and editor of the JAC newspaper Einikayt (Unity). Other prominent JAC members were the poet Itsik Feffer (1900-1952), a former member of the Bund, the writer Iliya Ehrenburg (1891-1967), General Aaron Katz (?-1952) of the Stalin Chief Military Academy and Boris Shimelovich (?-1952), the chief surgeon of the Soviet Red Army. A year after its establishment, the JAC moved to Moscow and became one of the most important centers of Jewish culture and Yiddish literature. In 1952, all the members of JAC were accused in anti-Soviet activity and executed.

In 1959, there were 17,167 Jews in Samara. By 1970, the number had decreased to 15,929, and then to 14,185 and 11,464, in 1979 and 1989, respectively. The decline in the Jewish population also reflected the start of the Jewish emigration to USA, Canada, and Israel during the 1970's-1980's. Despite the anti-Semitic campaign, the Jewish community in Samara survived during 1960s-1970's and tried to preserve a Jewish way of life. Members of the community decided to finance the activity of a rabbi and a shochet (ritual slaughterer). Shabbat and holiday prayers were held in the old Hassidic synagogue. The revival of Jewish life in Samara began in mid-1980s following the process of perestroika and openness in the former Soviet Union. The Jews of Samara were among the first in the Soviet Union to establish a Jewish cultural center in 1986 and a Jewish library in 1988.

Contemporary Jewish Life

During the 1990's, the Jewish community in Samara began to restore itself when a number of new organizations have been created, including the Union of Progressive Judaism's Haim, the womens' association Esther, and the youth organization Shomron – Bnei Akiva. In addition, three Jewish Sunday schools, a Jewish club, and the Open Jewish University started to function in Samara. The cultural society Tarbut la Am publishes a newspaper with a circulation of 3,000 copies. It is distributed not only to the Jewish community of Samara, but also in the towns along the Volga and beyond. Only one of the synagogues of Samara, a small Hasidic prayer house, was active during the years of the Communist rule. Underneath this synagogue is a mikve: very small but satisfying all the requirements of Halacha. Since 1991, the synagogue has served as the center of the Jewish religious activity, such as Shabbath and holidays prayers, kiddushim, the Sunday school, and a soup kitchen for the needy partially

run on local donations.

In 2002, the governor of Samara decided to return the now derelict building of the former Great Synagogue to the Jews of Samara. Beit Chabad, one of the thirty-one Jewish organizations in Samara, invested three million dollars into the reconstruction of the building with the aim of transforming the four-floor building into the future Jewish Community center of Samara.

In 1992, the Jewish National Center of Samara was organized. Rabbi Shlomo Deutch of the Chabad movement was appointed Chief Rabbi of Samara in 2000. In 2001 Roman Beigel was elected the president of the Jewish Community of Samara. In January 2002, for the first time after 100 years the synagogue of Samara received a new Torah scroll. The city is the center of Jewish activity for all 35,000 Jews living in the region of Samara. In 2003, about 10,000 Jews lived in Samara representing 0.67% of the total population of the city.

1 Following three decrees (ukases) of Catherine II in 1783, 1791, and 1794, a "Pale of Settlement" was created that restricted the Jewish rights of residence to either the territories annexed from Poland along the western border or to the territories taken from the Ottoman Empire along the shores of the Black Sea. Later, other annexed territories were added to the Pale and Jews were permitted to settle there as "colonists." Jews continued, however, to be banned from settling in the old territories of Russia.

Useful Addresses:

Jewish Community of Samara

Chapaevskaya str. 84 b

Samara, Russia 443099

Tel: (7 8462) 33-40-64, 32-05-29

Fax: (7 8462) 32-02-42

Synagogue

Chapaevskaya str. 84 b

Samara, Russia 443099

Tel: (7 8462) 33-40-64, 32-05-29

Fax: (7 8462) 32-02

Jewish Day School "Or Avner"

Maslennikova ave. 40-a

Samara, Russia 443056

Tel: (78462)70-42-74,34-32-79

Fax: (7 8462) 34-32-79