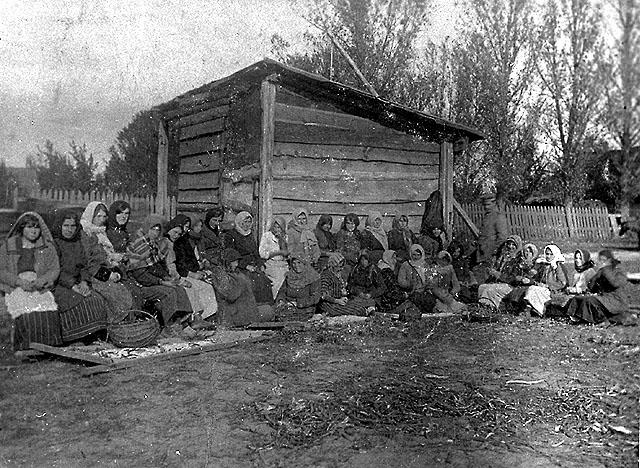

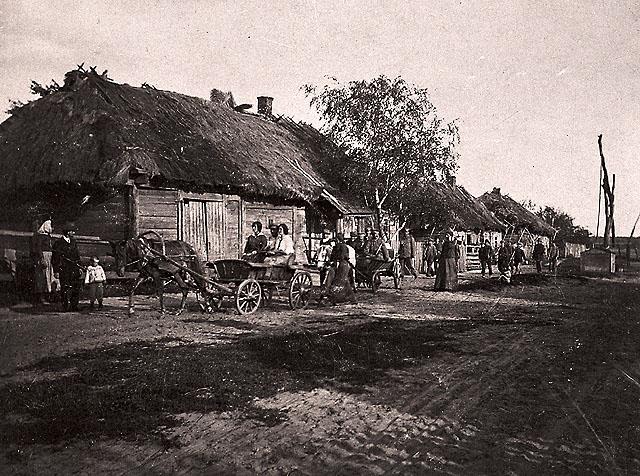

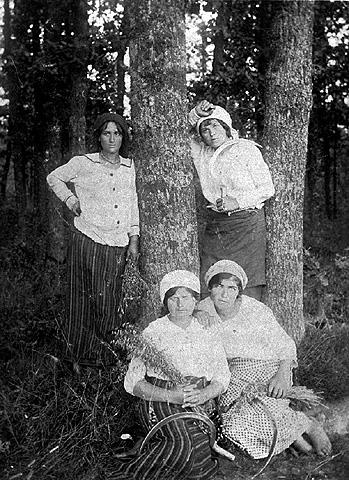

Pinsk Region, Polessia, White Russia, 1916/17.

The farm was founded by Jewish soldiers, who received the land after their military service of 25 years in the army of Czar Nikolai I.

(The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot,

courtesy of Tova Avida, Tel Aviv)

Pinsk

(Place)Pinsk

Пінск

Capital of Pinsk oblast, Belarus.

The Jewish community there was established before 1506 by some 12 to 15 families from Brest-Litovsk who settled in Pinsk. By 1566 the community consisted of about 55 families. It numbered over 1,000 (c. 20% of the total) in 1648. The Jewish population numbered 13,681 in 1871 (77.7%); 21,819 in 1896 (77.3%); 28,063 in 1914 (72.5%); 17,513 in 1921 (74.6%); and 20,200 in 1939. Pinsk thus remained a "Jewish town" until the holocaust.

Until 1648 the Jews were guaranteed the legal status of citizens, complete protection of their persons and property, freedom to engage in commerce, moneylending, and crafts, and the right to organize their internal life according to the precepts of their religion. The favorable geographical position of the region of Pinsk on the junctions of roads and waterways, and colonizing activity there during the 16th century, encouraged its development. Jews engaged in various activities including the ownership of estates, the lease of taxes and customs duties, commerce, moneylending, and crafts. In the middle of the 16th century, Pinsk Jews took up the then-thriving export of grain and forest products. As in the rest of the region, the Pinsk Jews benefited from the support of the catholic nobles against the Russian-orthodox Belarusian townsmen.

In these circumstances the status granted to the Pinsk municipality under the Magdeburg law in 1581 did not greatly hamper the Jews though it contained several restrictions on their trade. Pinsk was one of the three original leading communities of the Lithuanian council. It played a prominent role in the shaping of the council's policy and activity. The period between 1648 and 1667 was one of wars and misfortunes. At the time of the Chmielnicki massacres, Pinsk was taken on Oct. 26, 1648. Scores of Jews there were murdered in the town and on the roads, though most of them managed to escape in good time and were thus saved. A number of those who remained in the town became converted to Christianity, but later returned to Judaism. From 1667 until the beginning of the 18th century, the economic situation took a turn for the worse. Large-scale leasing disappeared, numerous Jews became impoverished and were compelled to seek new occupations, and many Jews of Pinsk turned to dealing in alcoholic beverages. Even the community administration itself had to borrow from them and from church officials, and gradually sank under a load of debt. The same social circles which had led the community before 1648 continued to do so until the close of the century. In these difficult times there were many scholars in Pinsk, and renowned rabbis held office. These include Naphtali Ginzburg, Israel b. Samuel of Tarnopol, Joel b. Isaac Eisik Heilperin, and Isaac b. Jonah Teomim Fraenkel. The rabbi and maggid Judah Leib Pukhovitser, who lived in Pinsk during the last third of the 17th century, exerted considerable influence.

The tense situation in Poland-Lithuania during the first quarter of the 18th century, the continuing economic crisis, and the burden of taxation and debts, gave rise to internal tensions within the community and to a conflict of interests between the community of Pinsk and its subordinate communities, whose numbers continued to increase during the 18th century. With the official abolition of the council of the lands in 1764, almost all the subordinate communities rejected Pinsk's authority, and after a prolonged struggle the weakened central community lost control.

Chasidism spread to Pinsk and Karlin during the 1760s. The community leadership adopted a neutral position toward Chasidism. However, under severe pressure by the community leadership of Vilna and Elijah b. Solomon Zalman, the Gaon of Vilna, the leadership of Pinsk associated itself with the ban against the Chasidim at the fair of Zelva in 1781.

Levi Isaac b. Meir of Berdichev was dismissed from his position as rabbi of Pinsk in 1785. In the same year, Avigdor b. Joseph Chayyim, an avowed opponent of Chasidism, was elected rabbi of Pinsk and district. However, he did not succeed in imposing his authority on the community, and the Chasidim regained their strength.

In 1793 Pinsk was incorporated into Russia and became a district capital in the Province of Minsk. At the beginning of Russian rule the economic activity of the Jews was reduced and their situation apparently became precarious. A change for the better began in the 1820s. The economic improvement in Pinsk continued during the 1830s, helped on by the government's economic policy which, among other measures, paved the way for the development of industry and the agricultural output of the Ukraine, and created opportunities for export of its agricultural surpluses.

Pinsk became a transit center for trade between southwestern Russia and the Baltic ports. Members of the Levin and Luria families held a prominent place in this commerce. The Jewish merchant class was broadened, its capital increased, and a stratum of white-collar workers and agents from Pinsk in the service of its wealthy merchants became active throughout the Ukraine. This prosperity in Pinsk lasted until the 1870s. During the 1850s a number of Pinsk merchants put into service steamships for the transportation of goods and passengers.

During the 1860s there were between 750 and 950 Jewish craftsmen in Pinsk. The philanthropist Gad Asher provided training for orphans and children of the poor in crafts, and the large number of Jewish artisans at this time was a feature of the city. In 1855 a Jewish agricultural settlement was established in the village of Ivanichi near Pinsk. At the close of the 19th century members of the Luria family established nail and plywood factories. A match factory was established in 1892. A Russian government school for the children of the Jews in the first category of merchants was founded in Pinsk in 1853, and during the 1850s to 1860s, 26 to 38 pupils studied there. During the same year a Jewish school for girls was established. In 1878 a private school, in which emphasis was placed on Hebrew studies, was founded by the Kazyonny Ravvin Abraham Chayyim Rosenberg. During the early 1860s Talmud Torah schools were founded in Pinsk and Karlin whose curricula included the study of the Hebrew and Russian languages and arithmetic in addition to religious studies. Many were still educated in the chadarim. In 1888 a vocational school was founded in Pinsk. During the 1890s modern chadarim were founded under the tutelage of the Chovevei Zion, whose members included the young Chaim Weizmann.

During the initial period of Polish rule after World War 1, on April 5, 1919, the Poles executed 35 prominent Jews following a framed-up charge against them. Between the two world wars the majority of the Jewish population in Pinsk was Zionist in orientation while a minority adhered to the bund and other parties. Many Jews emigrated to Eretz Israel, among them the members of Bilu, including Aharon Eliyahu Eisenberg, the founder of Rechovot, and Ya'akov Shertok. Kibbutz Gvat was founded in 1926 by pioneers from Pinsk. The Jewish educational network was widely extended. New Zion (with Hebrew and Yiddish as the languages of instruction); two Tarbut schools, one in Pinsk and one in Karlin; and the Chechick gymnasium (Polish). The Hebrew high school Tarbut, founded in 1923, existed until the beginning of the Soviet rule.

Under Soviet rule (1939-1941), Jewish institutions, including political parties and schools, were closed down. Some of the Zionist and bund leaders were arrested and many Jewish businessmen and members of the free professions were expelled from the city. A large number of Jewish refugees from western Poland found shelter in Pinsk. Pinsk fell to the Germans on July 4, 1941. A month later 8,000 Jewish men were rounded up and murdered. A similar aktion was carried out a few days later against 3,000 Jewish men, including the elderly and children. After these executions a series of repressive economic measures were enforced. On one occasion the Jews of Pinsk were asked to hand over 20 kilograms of gold.

The first head of the Judenrat was David Alper; he resigned after a short time and was executed in August 1941. He was succeeded by Benjamin Bokczanski. A ghetto was established toward the end of April 1942. In July 1942 all the patients in the Jewish hospital were murdered. Soon afterward, groups of Jews secretly organized resistance. On Oct. 28, 1942, the final aktion took place and all the Pinsk Jews, with the exception of 150 artisans, were killed. During this aktion a desperate attempt was made by the resistance group to break through the cordon of German soldiers. Some managed to reach the forests but were caught by the local population, and a very few succeeded in joining the partisans. On Dec. 23, 1942, the remaining 150 artisans were executed and the ghetto was liquidated.

In 1970 the Jewish population was estimated at 1,500. The last prayer house had been closed down by the police in 1966. The old Karlin cemetery, desecrated by the Nazis, was converted by the Soviet authorities into a park in 1959. The Jews did not comply with the request of the authorities to remove the bones for re-interment in the Pinsk cemetery.