The Jewish Community of Tripoli, Libya

Tripoli

In Arabic: طرابلس

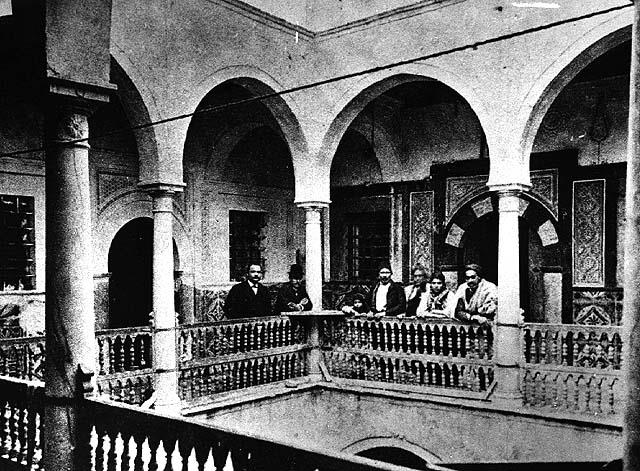

The largest city in Libya. Includes the Port of Tripoli.

Tripoli was founded in the 7th century B.C.E by the Phoenicians in the 7th century BCE who named the area Wiat (Oea in Latin). Towards the second half of the 2nd century BCE Oea was ruled by the Romans who designated it as part of Africa, and referred to the region as Regio Tripolitana, "region of three cities:" Oea (modern Tripoli), and its neighbors Sabratha and Leptis (modern Homs). A Roman road map from the 4th century indicates a Jewish neighborhood named Scina (or Iscina), Locus Judaeorum Augusti ("Scina, Locality of the Jews of the Emperor") in the vicinity of Oea; they were probably captives.

During the second half of the 11th century, there was a beit din in Tripoli that was independent from the Palestinian beit din. The Jewish community went through a difficult period under the rule of the Knights of Malta and Spain (1510-1551), but the Ottoman conquest in 1551 once again allowed the community to flourish, and many Jews from small rural communities began settling in Tripoli; there is evidence that at the end of the 16th century descendants of Spanish Jews who were expelled from Christian Europe also settled in Tripoli. During the 17th century Jews from Leghorn (Livorno) Italy, most of whom were merchants, also began to settle in Tripoli. During the reign of the Turkish Qaramanli Dynasty (1711-1835), Tripoli became a haven for Jewish refugees from Tunis and Algiers. The Jews of Tripoli played an important role in trade with Europe and Africa; others held diplomatic and consular positions.

The Jews of Libya were under the sole jurisdiction of the community of Tripoli. From the middle of the 18th century the presidents of the community represented Libyan Jewry before the government; during the period of Turkish rule, these presidents attended the governor's council meetings. They were also authorized to implement prison sentences, and to inflict corporal punishment on offenders.

In 1549 Rabbi Simeon Labi, a kabbalist from Morocco of Spanish origin, stopped in Tripoli on the way to Eretz Yisrael. Finding the population woefully ignorant of Torah, he decided to stay as a teacher; he is generally credited with the revival of Jewish learning in the city, and is considered to be one of Tripoli's greatest scholars. Abraham Miguel Cardoso, who would later become one of the leaders of the Sabbatean movement, settled in Tripoli in 1663. Beginning in the mid-18th century, the dayyanim and the prominent chakhamim of Tripoli mostly arrived from Turkey and Palestine, returning home after holding office in Tripoli.

In 1749 Rabbi Mas'ud Hai Rakah, an emissary from Jerusalem, arrived in Tripoli. He was joined by his son-in-law, Rabbi Nathan Adadi, who was born in Palestine and later returned there. Rabbi Rakah's grandson, Abraham Chayyim Adadi, settled in Tripoli after the 1837 earthquake in Safed and accomplished a great deal as the community's dayyan and chakham; he also retired to Safed. After his death in 1874, the Ottoman government in Istanbul issued a royal order appointing Elijah Hazzan as chakham bashi (chief rabbi); Rabbi Hazzan also represented Tripolitanian Jewry before the government. Subsequently, the Italian government continued this tradition after they first came to power and appointed Rabbi Elia Samuele Artom as chakham bashi.

In 1705 and 1793 the Jews of Tripoli were saved from the danger of extermination by foreign invaders. Two local Purim days were fixed to commemorate these events: Purim ash-Sharif on 23 Tevet in 1705, and Purim Burgul on 29 Tevet in 1793.

In 1835, Tripoli was again under Ottoman rule and the Jewish community once again flourished. Meanwhile, the Kingdom of Italy, which was established in 1861, attempted to exert its influence Tripoli, especially within the Jewish community. Indeed, the first European school in the city was established in 1876 by Italian Jews, responding to Jews in Tripoli who wanted to increase their economic and social ties with Italy. The community became divided between the conservatives, who generally supported the Turks and Ottoman rule, and those who favored Italy and were drawn to European culture. After the Italo-Turkish War (1911-1912), Tripoli became part of the Kingdom of Italy. During the period of Italian rule (1911-1943), the Jews of Tripoli enjoyed complete emancipation until World War II. They worked as craftsmen, traders, builders, carpenters, blacksmiths, tailors, cobblers, and wholesale and retail merchants; the textile trade and gold and silversmithing were exclusively Jewish professions.

The Paris-based school Alliance Israelite Universelle was opened in 1890 and ran until 1960 when it was closed after the mass immigration to Israel. By 1950 the city also had a Talmud Torah, a Youth Aliyah school, and a school for the children of Jews who had moved from villages to Tripoli. There were also Jewish children who attended Italian schools. There was also a branch of the Zionist sports and culture organization, Maccabi, which ran from 1920 until December 1953.

Until 1929, when internal conflicts prompted the Italian authorities to appoint a non-Jewish Italian official to take charge of the community's affairs, the Jewish community of Tripoli was run by a committee. Subcommittees were responsible for providing services for the poor. The community was funded through taxes on kosher meat, matzah sales, and community dues. In 1916 Zionists made up 11 of the 31 seats on the committee.

By 1931 there were 21,000 Jews living in Libya, most of whom lived in Tripoli. Their socioeconomic status was generally good until 1939 when the Fascist Italian regime began passing anti-Semitic laws. Jews were consequently fired from government jobs, Jewish students were not allowed to attend public or private Italian schools, and citizenship papers belonging to Jews were stamped with the label "Jewish race."

During World War II, the Jewish quarter in Tripoli was often used to store Italian anti-aircraft, and so was bombed by British and French forces; one attack left 30 Jewish people dead, and destroyed 4 synagogues. Jewish graves were stripped of their tombstones to provide fortifications, and the Jewish cemetery was also used for anti-aircraft positions and bombed. Nonetheless, the Jews of Tripoli were relatively fortunate. Those holding British or French citizenship were deported to the concentration camp Jado; the rest were required to supply workers for labor camps building roads and railroads. Though the living conditions in these labor camps were poor, the workers nevertheless received adequate food and medical care.

In spite of the war's hardships, in 1941 there was still a large Jewish community in Tripoli; 25% of the city's population was Jewish, and there were 44 active synagogues. In 1943, when the British liberated the city, the Jews of Tripoli numbered approximately 15,000.

The worst anti-Semitic violence in Tripoli would actually occur after World War II. In 1945, following Libyan independence, there was a pogrom in the city. During these riots 120-140 Jews were killed, hundreds more were injured, and property was looted; the British, who at that point were occupying Tripoli, were blamed for their slow response to the violence. A secret armed Jewish defense movement was formed after the pogrom. The pogrom would also set into motion the emigration of Jews from Libya.

Approximately 20,000 Jews lived in Tripoli in 1948. That year there were more anti-Jewish riots that broke out in Tripoli. This time the Jewish self-defense units, which had been organized after the previous pogrom, enabled the Jews to fight back against the Muslim rioters. In the end, 13-14 Jews and 4 Arabs were killed, 38 Jews and 51 Arabs were injured; there was also major property damage. What had been a trickle of Jewish emigration to Palestine after the riots of 1945 quickly became a flood of Jews leaving Tripoli for the new State of Israel.

According to the 1962 census, taken after the mass emigration to Israel during the late forties and early fifties, only 6,228 Jews remained in Tripoli (3% of the city's population of 19,000). The majority of Jews who remained after 1962 were wealthy merchants who were closely connected to Italy and lived there for part of the year. Further riots after the Six Day War in 1967 prompted most Jews to leave for Italy and Israel.

After Muammar Gaddafi came to power in 1969 he expelled the remaining Jews from Libya. He also confiscated all property belonging to Jews, and cancelled all debts owed to Libyan Jews. In 1970, there were only several dozen Jews living in the town. By 1974 there were no more than 20 Jews in Libya. By the end of the 20th century there were no more Jews in Tripoli; the last Jew left in Libya was granted permission to leave for Italy in 2003.

TRABULSI

(Family Name)TRABULSI

Surnames derive from one of many different origins. Sometimes there may be more than one explanation for the same name. This family name is a toponymic (derived from a geographic name of a town, city, region or country). Surnames that are based on place names do not always testify to direct origin from that place, but may indicate an indirect relation between the name-bearer or his ancestors and the place, such as birthplace, temporary residence, trade, or family-relatives.

This family name is derived from Tarabulus (طرابلس), the Arab name of the cities of Tripoli in Libya and Tripoli in Lebanon. Both cities were home to Jewish communities for almost two thousands of years.

Places, regions and countries of origin or residence are some of the sources of Jewish family names. But, unless the family has reliable records, names based on toponymics cannot prove the exact origin of the family.

Trabulsi is documented as a Jewish family name with Yemima Trabulsi, Director of Eshkol Payis Science, Arts, and Technology Center in Gilo, Israel, during early 2020s.

Stories from Libya - Miriam Haiun

(Video)Stories from Libya - Miriam Haiun

Miriam Haiun is a Jewess born in Tripoli, Libya. Her family moved to Tripoli in the 1950s. Her father had a general store where it was possible to find everything, from imported food to clothing. In 1962 they returned to Milan in Italy, where some family friends lived, when she was only seven years of age, a few years before the pogroms. Miriam's memories are linked to the stories of her sisters and some uncles who escaped from Tripoli in 1967. Her sisters were much older than her and remembered only pleasant things about their life in Libya, where they attended only Jewish circles. In Israel, where she studied at the university, she realized that Sephardi Jews were viewed with superiority.

This was probably due to the fact that the Jews of Tripoli did not enjoy privileges such as the right to vote, the ability to join the army or to study at a university. The restrictions they had been submitted to included getting off the sidewalk so that they may give way to Arab pedestrians. Any business could be opened only in partnership with an Arab. Jews were "second-class" citizens or "dhimmi", the term by which Jews were designated in Libya.

Miriam's family still observes the customs of Tripoli, especially related to culinary traditions. The kosher cuisine includes many dishes that are still prepared today, particularly on holidays. Dishes from the Italian culture, dear to her husband, are prepared as well. Miriam tells of the particular musicality of her father's way of praying, typical of the Jews of Libya. Even today Miriam and her family use some typically Arabic expressions to define certain situations. Miriam really feels at home in Rome and believes that, although the confiscation of assets and properties was an injustice, trying to recover them is a lost cause because there is, at the moment, no one to talk to.

She mentions: “The conditions do not exist: a path of peace between Libya and Israel would be necessary for a dialogue to be established and unfortunately at the moment this possibility is far away. It would be nice to preserve sacred places in Libya but who could then guarantee their maintenance? No Jew is allowed to reside there. Who could protect the eventual construction of a memorial for the victims of the Shoah and who would guarantee the respect over time of this monument. It would be important, especially for Libya, to preserve the trace of our history for the benefit of future generations."

Miriam is the director of the Jewish Culture Center in Rome and has conducted many interviews to preserve the memory of the Holocaust, which are published on an oral history site. In many recordings the interviewees mentioned how happy they were to have left Tripoli and to be able to enjoy the freedom that was not granted to them in Libya, where they belonged to an invisible and mute minority.

This film is part of Storie di Libia, a series of video testimonies of Libyan Jews produced by Dr. David Gerbi, a Rome based Jungian psychologist, psychotherapist, analyst and a writer. The original Italian abstract was published, on June 28, 2021 at https://moked.it/blog

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish people, courtesy of Dr. David Gerbi, Italy.

Penina Meghnagi Solomon recounts her childhood in Libya, 2013

(Video)Penina Meghnagi Solomon, a resident of Valley Village, CA., was born in Tripoli, Libya. In this testimony of 2013 she recounts her childhood in Libya.

Pnina Meghnagi Soloman was born in 1949 in Tripoli, Libya. Her name, Pnina, means “precious stone” in Hebrew. Pnina has happy memories of being a young girl in Tripoli, Libya where she spent her childhood soaking the city’s warmth nearby the ocean, always surrounded by friends and family. Some of her earliest memories include guests coming in and out of her house talking around two long tables with a white tablecloth, eventually cementing her values of family and being welcoming.

The Jewish neighborhood was known as “Hara,” which was located behind a castle that oversaw the walled city of Tripoli. Pnina’s house was near a white church, and her synagogue was just down the block from her house. The importance of the Jewish religion was instilled deeply within Pnina, as her mother comes from a long line of rabbis and religious court judges known as diyanim from the Island of Djerba (in Tunisia).

The family’s Shabbat custom was to eat couscous with either chicken soup, along with spicy fish called hairame and special meatballs called mafrum, containing slices of potatoes with meat inside, fried and cooked in sauce. Dessert was always cakes and fruits.

The residents in Pnina’s neighborhood generally lived among each other in harmony, no matter which religion they practiced. Her neighborhood included Jewish, Muslim, and Christian Italians, Egyptians, Libyans, and Maltese. Libya’s diversity at the time nurtured Pnina’s friendship with her Italian, Egyptian and American neighbors, as well as the children of the Sheikh from her neighborhood. In her city of Tripoli, Pnina was exposed to the whole world.

Despite the blend of differing religions and ethnicities, Pnina says that there was always a worry in the back of her mind that she or her family may be harassed or attacked for being Jewish. In November 1945, during the infamous anti-Jewish Tripoli pogrom, Pnina''s Uncle Gabriel Menaghi had had been slaughtered at his doorstep. He was one of an estimated 140 Jews who were killed during the violent pogrom.

There was also a fearful mindset within the Jewish community as a whole. Jews thus refrained from wearing Maghen David jewelry, they also refrained from displaying the Star of David or the Israeli flag in any form. Jews were considered second-class citizens.

“The true Muslims who really knew the religion of Islam always had respect for the other,” she recalls. “But, as Jews we had a fear that there was a certain boundary we could never cross. We were called dhimmis, we were degraded and we were always a step down from the Muslims.” While Zionist organizations were officially prohibited, some Jews, including Pnina, participated in the underground B’nei Akiva Zionist youth movement. She remembers learning the famous Hebrew Tu’bishvat Higiyah song in Tripoli despite the fact that the movement was prohibited from displaying any flags.

The most devastating problems, which led to the end of the Jewish community in Libya, started in 1967 with the break out of Israel’s Six-Day War with its Arab neighbors. At the time Pnina was working part-time and going to school. One day she was suddenly instructed to go home; the radio had announced that there was a war in Israel. Mobs of Libyans turned their rage towards Israel against their fellow Jewish Libyan citizens. They pillaged, burned and destroyed the neighborhoods and killed innocent Jewish people.

Pnina had to go into hiding and she counted on her neighbors to bring her family kosher food. One day, a crowd armed with machetes descended on her neighborhood looking for the Jews. Her local Sheikh came out on the street and told the crowd “mafich Yehud, no Jews here.” The Sheikh’s lie caused the mob to leave, saving the lives of the Jews still hiding throughout the neighborhood.

None of the Jews knew what they were going do and Pnina’s mother, a widow with four children, began to panic. Pnina remembers an official from a local government office had already once indicated to her mother that the day was coming where her throat would be cut. Unlike many other Libyan Jews, Pnina’s mother had a Tunisian passport, as she predicted that if the Jews needed to one day flee Libya, it would be easier to do so with a foreign passport. On June 30th, 1967 at 4:30am a government Jeep came and took the family to the airport. Pnina remembers that it felt strange to her as she underwent a full body search. The Jews were only allowed to take one suitcase and 20 Libyan Sterling.

Since Libya had been an Italian colony, her family spoke Italian. The organized Jewish community in Rome welcomed her family in Italy.

At the time, there was an international refugee camp. Communism was prevalent and refugees from Poland, Hungary, Romania and other communist nations would flee to refugee camps in Italy. The two most famous ones were known as Latina and Cerata. Her family moved to Latina where they received extra clothing and assistance in finding mediocre jobs to get back on their feet. Pnina had been taking an English class in Tripoli and she was able to continue it in the same school in Latina. Her family was able to slowly rebuild their life in Rome.

Back in Tripoli, Pnina’s mother washed the dishes and made the bed before their departure to Italy, though she knew that they would never return to Libya. They had left behind a home with furniture, toys, and everything that was their old life. Pnina’s Arabic teacher was also a close friend of her mother’s. As the family was preparing to leave, Pnina’s teacher visited and offered to do anything she could do to help them. Pnina’s mother gave Pnina’s Arabic teacher her silverware for safekeeping, hoping that they would meet again. Just one year later the Arabic teacher’s son visited Italy, which is when he returned the silver to Pnina’s family. Even now, Pnina remembers it as a most caring gesture during a time of great darkness.

Despite the Arabic teacher’s kindness, Pnina still laments on the loss of her family’s belongings and the memories they represented. As the Libyan government froze the bank accounts of all departing Jews, they had little with which to start their new lives elsewhere. Their departure to Italy meant that they would have to rebuild their lives from scratch.

While the memory of starting her life over is difficult, most painful to Pnina is the destruction of Tripoli’s Jewish cemetery. Pnina muses that if the Jewish cemetery still existed, she would go back to Tripoli to visit the graves of her father, grandparents and hundreds of other Jewish Libyan ancestors. With the Jewish cemetery destroyed, Pnina says, it symbolizes that even the dead Jews are prevented from resting in peace in Libya.

Leaving Libya also shattered the dynamic in Pnina’s family. Pnina was the oldest in a family of five children, and served as a second caretaker to her siblings after her grandmother had moved to Israel in 1951. Pnina’s mother decided it would be better for the older children to get out of the refugee camp and settle into a normal life. The younger children, however, were moved to Israel to live with their grandmother after the first year in Italy when the family was altogether. The older children then learned to speak Italian but not Hebrew, while the younger children learned to speak Hebrew but not Italian. With a new language gap to overcome, the family began to communicate with one another in Judeo-Arabic.

This film is part of the Testimonies produced by Sarah Levin for JIMENA's Oral History and Digital Experience. JIMENA - Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa - is a San Francisco, CA., based non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of culture and history of the Jews from Arab Lands and Iran, and aims to tell the public about the fate of Jewish refugees from the Middle East.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot, courtesy of JIMENA.

Stories from Libya – Lucky Nahum

(Video)Stories from Libya – Lucky Nahum

Lucky Nahum is a Jew born in Libya. His second given name was given to him in the United States when he obtained American citizenship, twice lucky. Thanks to the skills of the family patriarch who had settled in Libya, his family was active in a number of economic fields that included real estate, agricultural land and vineyards. They lived in a magnificent villa. The father of the family was famous for his generosity towards the local population, particularly towards the poorest. A fame that unfortunately cost him his life: ten Arabs tortured and killed him during a robbery. Lucky recalls the difficult relationship with the Arab population, the need to avoid places where Jews were not allowed to enter. Along with Jewish, Christian and some Arab boys he attended the best school in Tripoli. He mentions that the Americans don't understand that kind of nostalgia for the land where you were born. Despite the discomforts he was used to, the scents and sounds of that land have always remained in his heart. But he never wanted to go back. He emphasizes: "It is better to die on your feet than to live on your knees". His family was aware that they were walking on egg shells. If someone mistakenly dropped a coin, he could be accused by Muslims of not loving the king because king’s portrait was imprinted on it.

He remembers a friend who suddenly showed up and encouraged them to run away immediately. His mother was reticent, they cared a lot about their home. He remembers that, in order not to arouse suspicion, they paid the Muslim domestic worker in advance and informed her that they would go on vacation for a few days. They also decided to move to the city center, so that they would not be isolated in those times of turmoil. They were personally assisted by a relative of the king who was linked to his family. Nonetheless, he allowed them to leave with only $25 and one suitcase each. Her mother took care of the suitcases. One of them contained only photographs, the other his elder brother's study books.

Arriving in America, after a short stay in the refugee camp of Capua in Italy, he rolled up his sleeves along with his parents. His father started working in a factory and after a short time he opened his own business. His brother currently helps the government educate medical and paramedical staff about safety procedures in sensitive environments. Lucky Nahum devoted himself to studies, believing that in the future he could educate people to be less ignorant and to prevent many mistakes. He then decided to pursue a career in business. The well-being achieved has prompted him towards works of charity: now he is chairman of Israel Resource Center, an organization whose mission is educating for peace. Jewish history, he says, always teaches us that with a few dollars in your pocket and without complaining about your adverse fate you can do many things. “Why mourn for something we can't change instead of honoring the life we have been granted? - reflects Lucky Nahum. With age, the need to tell and pass on the story becomes more urgent, without victimization, but including the testimony of the saddest and most brutal traits. For Lucky Nahum it is not easy to talk about the past and he savors the joy of feeling free every day. He thinks it makes little sense hoping to get his possessions back (his family had tried, but then preferred to abandon this attempt). The most important thing he would like to be preserved is the memory of the Shoah. Many people did not even know that there had been Jews in Libya for two thousand years and what had happened to them. Not even contemporary Libyans. Lucky Nahum doesn't really feel at home in the United States and he is intimately connected to Israel where he would like to live in a city by the sea. A city with the colors, sounds and smells of his native land. But with the significant difference of being free.

This film is part of Storie di Libia, a series of video testimonies of Libyan Jews produced by Dr. David Gerbi, a Rome based Jungian psychologist, psychotherapist, analyst and a writer. The original Italian abstract was published, on July 5, 2021 at https://moked.it/blog

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish people, courtesy of Dr. David Gerbi, Italy.

Stories from Libya - Clemente Bublil

(Video)Stories from Libya - Clemente Bublil

Clemente Bublil is a Jew born in Tripoli, Libya. He lived with his well-off family close to the King's Residence, in a house built by his father. Like many Jews of Tripoli, he was educated in England. He recalls the rule: if a member of a Jewish family left Libya, he could not be followed by others, who had to stay behind as hostages. Of Libya he strongly remembers the fear, the lack of freedom, the humiliations and the threats from boys armed with knives and hatchets.

Women rarely went out of their homes. Like many other young people, they could be kidnapped and forced to marry against their will to Muslim citizens. His father saved fifty-two from such a sad fate. His father very rarely spoke of Libya to his children. It was difficult to find positive memories. Being free and not persecuted was the strongest feeling upon arrival in Italy, like that of having escaped a horrible end. In 1967 businesses, shops, houses were burned or confiscated from Libyan Jews, people who lived in that country for two thousand years. His mother's wedding ring was also ripped from her fingers. After arriving in Italy, with only 25 pounds in his pocket, each member of his family showed resilience, the ability to build a future for themselves and their children. Especially in Rome and Milan, the Jews of Tripoli opened clothing companies, now prestigious. Since they settled in Rome the kasherut was much improved. In 1967 there was only one butcher's shop, while today there are fourteen. In addition, eight synagogues following the Tripoli rite have been opened in various parts of Rome. The Jews of Libya integrated and actively participate in Italian economic life. Many got married to Roman Jews and a beautiful dynamic, active, and enterprising youth ensued. From Libya Clemente keeps the culinary traditions and the prayer rite. He remembers the greatness of important Libyan rabbis. He feels he has been robbed of his possessions and would like to be recompensed for the wealth extorted for no reason, but recognizes the futility of fighting to preserve what remains of synagogues and cemeteries, because many Islamic fundamentalists teach and profess hatred towards Jews and aim to wipe out everything related to Judaism. Synagogues and Jewish cemeteries were desecrated and demolished to build roads and buildings. Unfortunately, hatred comes from ignorance: they have learned to hate everything that is not Islamic. Clemente hopes that sooner or later they will learn to love. But he doesn't want to generalize. There are Arab countries such as Morocco in which Islamism does not take on such dark colors. This is demonstrated by the Abrahamic Pact recently signed by some Arab countries and Israel. When he was young Clemente felt the desire to fight. He left the comfort of his Italian home and moved to Israel where he served in the IDF as a "lonely" soldier, that is, a soldier that does not have relatives in the country. He risked his life and when this period ended he really began to appreciate every little thing and savor every moment. In Rome he got married and had children. He is keen to point out that in Israel the Arabs are respected, like their mosques, and enjoy maximum freedom, health care and financial support in case of need. He tells us: "Israel is the only strong bulwark against Islamic extremism, a point of reference for every Jew. If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning” (Psalm 137:5). He exhorts young people to be united and always help Israel, defining it as the true refuge of every Jew, to study and attend the synagogue, live coherently and correctly and respect the values.

This film is part of Storie di Libia, a series of video testimonies of Libyan Jews produced by Dr. David Gerbi, a Rome based Jungian psychologist, psychotherapist, analyst and a writer. The original Italian abstract was published on June 14, 2021 at https://moked.it/blog

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish people, courtesy of Dr. David Gerbi, Italy

Stories from Libya - Jojo Naim

(Video)Stories from Libya - Jojo Naim

With a smile on his face Jojo Naim recounts his grandfather who declared that he wanted to go to hell so that he can be together with his daughters who used to smoke secretly on Saturdays.

Jojo Naim lives in Miami, Florida, and traveled a lot having been an airplane pilot for 40 years. He considers himself "very Jewish", although he is not particularly observant. In Libya he never had friends outside the Jewish community. On the contrary, he strove to escape a small groups of mobsters who used to beat him and other Jewish boys for no reason. Each time they played basketball against Arab boys and won, the match ended with a shower of stones. Jojo Naim did not suffer the trauma of leaving Libya: for him the trauma was living there without freedom, as a dhimmi citizen.

One day, he was then only 14, Jojo overcame two boys who wanted to beat him. After a few days a funeral procession passed under his house and those boys started to scream claiming that he had spit on the dead from the balcony of his house. It was obviously a horrible lie. Many Arabs besieged the house and the police were forced to guard the entrance to prevent them from lynching him. So he was forced to leave Tripoli, alone, as a teenager, for Naples in Italy. There he lived in the house of some Catholic friends of the family who hosted him and made him respect his religion by sending him to pray every Friday in the synagogue. He was joined in Italy by the rest of the family after two years and soon they all moved to Venezuela.

After a few years Jojo Naim, with his new passport, returned to Libya to visit his relatives. Not even the beaches of which he kept nice memories had seemed beautiful to him, at least when compared to those of Italy or Venezuela. There were no riots at that time, but he remembers the great darkness that seemed to pervade Tripoli.

Jojo Naim speaks of Jewish predisposition for suffering that leads to react and redeem oneself. And this applies to all Jews who had to leave the Arab states.

He cultivates family culinary traditions and says he found a Libyan basketball champion, Duccio Nemni, in Santo Domingo. Regarding the possibility of requesting compensation or not and stopping the destruction of synagogues and cemeteries, he observes: “No Jew forced to leave an Arab state has never been compensated. Why tempt us? I love to fight, but not for lost causes. We cannot change their mentality. Everywhere churches and synagogues have been transformed into mosques”. Then he adds: "Whoever does not learn from his story is condemned to repeat it".

Miami is his home, the place where the people he loves and who love him live. But United States, he recalls, also marginalized Jews in the past. He concludes the interview by explaining that he celebrates more than one birthday because he also celebrates the day when, as a very young child, he survived a bombing that had destroyed both his cradle and his room, as well as the day when he was saved from a serious plane crash.

This film is part of Storie di Libia, a series of video testimonies of Libyan Jews produced by Dr. David Gerbi, a Rome based Jungian psychologist, psychotherapist, analyst and a writer. The original Italian abstract was published on July 5, 2021 at https://moked.it/blog

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish people, courtesy of Dr. David Gerbi, Italy

Stories from Libya - Penina Meghnagi Solomon

(Video)Stories from Libya - Penina Meghnagi Solomon

Penina Meghnagi Solomon was born in Tripoli, into a Jewish family who lived in Libya for many generations. Her father was engaged in import and export; he also was known as Libya's swimming champion. Her mother was a housewife who took care of the family with the help of a domestic worker. She loved sewing, embroidering and receiving guests. The entire family respected the rules of a peaceful coexistence and was aware of the inevitable intolerance of some residents. The Jews of Libya avoided gathering with other Jews so as not to provoke the susceptibility of narrow-minded Libyans, but they lived in peace with respect for faith and traditions. In 1963 the father had passed away, the younger children were only two or three years old, and the mother, albeit with difficulty, managed to support the family. Despite the many difficulties of living in an Arab country, the life went rather peacefully for the youngest, protected by the illusion of being able to enjoy serenity.

In 1967, all of a sudden, the world around them was no longer the same. Forced into hiding, they watched unarmed the fires being set to Jewish-owned shops and the confiscation of their assets. They had to hide from the aggression of their Muslim fellow citizens who were prepared to kill them on the streets. They were forced to flee, with only their documents, so that they will not be killed. Until a few days before, Penina was happy, she was thinking about the sea, the holidays, the future studies at Oxford. Suddenly she left behind everything: her doll, school, friends, the turtle on the veranda, her home. Her family dispersed into the world: Italy, Canada, United States, Israel. Penina no longer remembers the tragic moments experienced, probably due to her personal reaction to her trauma. However, she kept a diary of those days and still browses it today to remember and tell her story to her grandchildren. With her sister Denis and her mother, they rolled up their sleeves and without being discouraged by the violence they suffered, they did their best to ensure that the following generations grow in peace and with confidence in the future, while keeping alive the memory of a difficult past but without feeling sorry for themselves.

Like so many Jews of Libya, her family continued to prepare traditional Libyan dishes and still celebrates in the same way they used to do in Tripoli. Penina does not consider the entire Libyan people guilty of the events. Sheih, a Muslim family friend, hid them saving their lives and a Muslim friend of their mother's kept and brought them the money, a year later, in Italy.

She does not wish to return to Libya because she believes there is nothing left for her there, and she believes that hoping to get her family's assets back is pointless. Furthermore, the graves of her loved ones on which they used to pray do not exist any longer. Highways and buildings have been built on the places where Jewish cemeteries were located. She hopes that merciful Arabs have thrown their bones into the sea and on commemoration days she goes to the sea with her family and throws flower petals on the water. According to her, Libya lives inside the hearts of the Jews of Libya, in a plate of couscous or hraimi, in a jewel handed down from her grandmother or in a coffee with orange flowers. She tells us: “We tell our story to teach and pass on to young generations the awareness of belonging to a great people united by faith and not by borders, citizens of the world, but always tied to our traditions. My experience and trauma led me to have two mottos: 'Let's celebrate the present' and 'You can be sure where you wake up, but never where you will sleep'. We are Jews and we never give up! I think that only in Israel it’s possible for us to feel safe and free. I would be happy if Libya became a free and open country and respected the memory of our people as part of two thousand years of Libyan history. It would also be fair to the valuable Muslims, who deserve to live in peace. A memorial to the pogroms against innocent Jews would be a just warning for the future and a great gesture of tolerance and respect towards our people”.

This film is part of Storie di Libia, a series of video testimonies of Libyan Jews produced by Dr. David Gerbi, a Rome based Jungian psychologist, psychotherapist, analyst and a writer. The original Italian abstract was published, on June 21, 2021 at https://moked.it/blog

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish people, courtesy of Dr. David Gerbi, Italy

Stories from Libya - Yoram Ortona

(Video)Stories from Libya - Yoram Ortona

Yoram Ortona, the son of Marcello Ortona and Doris Rachel Journo, is an Italian Jew born in Tripoli, Libya, in September 1953. His mother, of Tunisian origin, was an observant Jewish woman. She was a very beautiful woman, blonde with blue eyes that had been elected Miss Maccabi in her youth. His father, of Italian origin, more traditionalist and Zionist, at the age of 23 became director of the Corriere di Tripoli, a newspaper of the Public Information Office (P.I.O.). A brilliant career. On November 1, 1945, however, the first anti-Jewish pogrom broke out. He was the first to receive those yellow envelopes stamped "Very Urgent - Top Secret" which contained news of the riots and the names of the victims.

A beautiful family who lived in Tripoli in more than decent economic conditions and led a happy life, until June 5, 1967. While Yoram was preparing an essay for the middle school exam, the principal interrupted the test and put him in telephone contact with his father who ordered him to run immediately to his uncle's house, that was closer to the school than their own home. A great mass of angry people had started a hunt for Jews on the streets of Tripoli. Numerous Jewish shops and houses were set on fire as well as many synagogues. With his bicycle, avoiding the angry crowd, he headed for his first refuge.

Yoram remembers with emotion the acrid smell of smoke, impossible to forget, even after such a long time. When they heard the strong knocks on the door of the mob who attempted to break into the house, they took refuge on the terrace and he heard his aunt saying to her husband "If they come in, let's jump downstairs, let's not allow them to lynch us!".

But they managed to overcome that terrible moment and his father joined him at sunset, in a car driven by one of his Berber collaborators, so as not to arouse suspicion. Yoram went with him to pick up his little brothers from a school run by nuns and take them to the district of Al Dhara in central Tripoli. The nuns initially did not allow the Berber driver to take the children, evidently to protect them, but immediately handed them over to their father when he got out of the car. For 12 days they lived barricaded in the house with the shutters down and in total silence for fear and anxiety, with the electric light on all day.

His father, due to his position, had a lot of acquaintances at the Italian embassy, and also because a few years earlier he had been awarded the Cavaliere al Merito of the Italian Republic for journalistic merits. So he managed to find four seats on an Alitalia flight bound for Rome: five left, with a 5-year-old girl on their father's lap. Yoram still remembers the skyline of Tripoli, the waterfront, the palm trees and the cathedral that receded out of his sight for the last time. At the airport their mother had removed the last jewels and so, like all the other Jews, they left with two suitcases and twenty Libyan pounds that no one in Rome wanted to change. Landing at Fiumicino, he was dazzled by an advertising sign inviting visitors to visit Israel and Golden Jerusalem. He was very impressed because at school, on the geographical atlas instead of Israel there was a paper cutout glued by the censorship of the Libyan government.

For him and his family having been forced to escape and avoid being killed was a trauma. But Yoram also has good memories of Tripoli and he gladly recounts them. Given the current situation in Libya, he would not want to go back, even if his maternal grandparents are still buried there. He is frightened by the hatred that today still incites some Arabs against Jews, as we saw a few months ago even in Israel. He preserves many traditions common to the Jews of Libya, in addition to the typical cuisine, such as synagogue chants. He is happy that along with his wife Dalia they passed them along to their children.

Yoram is an architect and has lived in Milan for 40 years. He has traveled a lot abroad for work and often went to Israel. He mentions: “Israel is like my mother, my cradle. Milan with its culture and Italy are like they were my father! "

Like many Jews he says he lives for the day. Finally, he shows a publication entitled "The forgotten pogrom". Once upon a time there were synagogues in Libya, the rediscovered testimony of the editor of Corriere di Tripoli.

Here are the comments written by his father in a poetic style. He quotes: “The tear for what our fathers grandfathers and great-grandparents had considered and loved as our homeland all their lives is inhumane to death. But it was far from being a disaster. On that plane we were fleeing towards luck! Time is an unparalleled ointment that has no rivals: it licks wounds and relieves pain, even the strongest. And when after the first legitimate outbursts of despair, with a cold mind you pass from tension to meditation, reason has the upper hand, and wins. As for us it was the same as for all Jews who had cried for losing Tripoli”.

This film is part of Storie di Libia, a series of video testimonies of Libyan Jews produced by Dr. David Gerbi, a Rome based Jungian psychologist, psychotherapist, analyst and a writer. The original Italian abstract was published on July 19, 2021 at https://moked.it/blog

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish people, courtesy of Dr. David Gerbi, Italy

Stories from Libya - Raphael Barki

(Video)Stories from Libya - Raphael Bark

Raphael Barki is Jew born in Tripoli, Libya. His mother, the daughter of a religious Jew, was quite observant while Raphael’s father, whose father arrived in Libya by mistake, having boarded the wrong ship while he was sure he was travelling to Tripoli in Lebanon, was rather a traditionalist than a religious Jew. The Barki family owned a renowned fabric shop in the city center and enjoyed a good standard of living. In June 1967 Raphael was only four and a half years of age, so he only has a faint memory of his life in Libya. Of those fateful days, just before the escape, he remembers having sheltered in their home a family of Jewish friends to protect them. And then the din of the screaming violent crowd which, in the eyes of a child unaware of the threat, became just an excuse to play hide and seek by taking refuge behind the armchairs of the living room, which overlooked the main street.

After arriving in Italy, they lived during the first months in Rome and then moved to Milan, where Raphael's paternal uncle owned a well-established commercial activity that they carried on in partnership. He tells us with a smile that his mother feared that Raphael's excessive vivacity was linked to the trauma, but in reality he had no memories that could be traumatized ... he was just a very lively child.

Like many other Jews of Tripoli, Raphael's father also rolled up his sleeves and started building a future for his children. He too, like almost all Jews from Libya, did not ask for financial help from the Jewish community, but took upon himself the work reconstruction.

Some elders of the Jewish community of Libya still remember the good times they spent in Tripoli, where they lived in a kind of bubble, as Raphael defines it: the comfort, the beautiful houses, the walks along the Corso, the dancing evenings. Pleasant memories that, however, cannot ignore the fact that the Jews were still and always regarded as dhimmi, second class citizens, and subject to discrimination. Only some of them still dream of returning to Libya crying for what they have lost, while most put the past behind them and built a dignified future for their loved ones.

Raphael lives with his family in Israel, where he moved in 1996. Older Tripolitans had to deal with the label of "primitive Tripolitan" affixed to them by Israelis of European origin. But Raphael's generation was already free from these prejudices and he, who has always been motivated to get back on track due to his legacy, has managed to successfully integrate himself in society and in work.

Raphael cultivates the memory of his roots especially by cooking traditional dishes and feels at home in Israel, but also in Italy where he has lived for many years and where his mother, sister and brother live with their respective families.

Asked whether it is worth seeking compensation or restitution of confiscated assets despite Muamar Gaddafi’s lie, according to which "the confiscated assets of the Jews of Libya actually compensate for what was stolen from the Palestinians”, even though the Libyans have never given the Palestinians any of their seized wealth, Raphael replies that this request should be carried out not so much by individual Jewish refugees of Libya, but rather be part of wide-ranging negotiations between Israel and the Arab and Muslim countries, which are responsible for creating about nine hundred thousand Jewish refugees during the postwar period.

Regarding the preservation of synagogues and cemeteries still existing in Libya and the construction of a memorial dedicated to the victims of the pogrom, he believes that Israel could promote the initiative when there are favorable conditions and reliable interlocutors in Libya. Libya should first become a free and democratic country and that the Arabs, among which anti-Semitic hatred is still strong, should learn to recognize the richness of diversity. He fears that a monument could actually become a new target for spitting and vandalism by some of them, something that must be avoided.

Raphael has created and manages “Mafrum for all”, an online group of about 1,800 members, aiming to collect experiences and testimonies from the Jews of Libya in Israel and in Italy. As the name promises, sometimes the tones of the discussions can become spicy like aharaimi (hraimi) and tasty like mafrum, fully reflecting the character of the Libyans.

This film is part of Storie di Libia, a series of video testimonies of Libyan Jews produced by Dr. David Gerbi, a Rome based Jungian psychologist, psychotherapist, analyst and a writer. The original Italian abstract was published on July 26, 2021 at https://moked.it/blog

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish people, courtesy of Dr. David Gerbi, Italy

Stories from Libya - Betti Guetta

(Video)Stories from Libya - Betti Guetta

Betti Guetta is a Jewess born in Tripoli, Libya. She dedicates this interview to the memory of her parents. Her family was observant and traditionalist. She has no memories from Libya because the family moved to Italy in 1957, when she was only 11 months old. Her father decided to take this step because he feared the future. He went to Milan, where he had no family, and opened a business. At home they spoke in Italian and Arabic. They remained stateless for about 14 years, but a strong Jewish identity prevailed at home. Betti currently considers herself integrated. She remembers some moments from the summer holidays spent at her grandmother's house in Tripoli. She has some vivid memories of the Hara (Jewish district) and of Tripoli beach. Her grandparents in Libya wore typically Arab clothes. She remembers that they went to the sea in the carriage and that once, returning from the sea, while she was getting off the carriage, a group of Arab children threw stones at her and fought with her cousins who rushed to her aid. In 1967 many of her family members lived in Tripoli and all managed to save themselves. She remembers from Tripoli that everyone in the house was called uncle and aunt and that there was a sense of unity and familiarity among Jews. In her opinion the Jews of Libya have a great deal of resilience. Her family has preserved Libyan Jewish religious and gastronomic traditions.

Betti tries to maintain the traditions, and despite a non-observant way of life, she expresses the depth of her religiosity. She keeps using phrases like "If God wills”, “if God does not want", and "we do not know what is in store for us, but our faith in God gives us great strength".

Betti lives in Milan where there is not a community of Jews from Libya as large as that in Rome. She considers herself integrated into Italian society, but with "a background of Arab music". From her school days she remembers the families of her colleagues: those who came from Egypt spoke with nostalgia of the good old days, while those who came from Tripoli were happy to have escaped from Libya.

She would like to be able to see Tripoli and visit the graves of her grandparents, but tis is a remote thought. She knows that it will not be possible and she would still be afraid to go there. She believes it is rightful that people could get back the property that was confiscated from them.

She has a composite identity; she feels at home in Italy as well as in Israel.

This film is part of Storie di Libia, a series of video testimonies of Libyan Jews produced by Dr. David Gerbi, a Rome based Jungian psychologist, psychotherapist, analyst and a writer. The original Italian abstract was published, on August 2, 2021 at https://moked.it/blog

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish people, courtesy of Dr. David Gerbi, Italy.