The Jewish Community of Sarajevo

Sarajevo

In Jewish sources: Sarai de Bosnia

The capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Sarajevo has been called the "Jerusalem of the Balkans," a testament to the city's multiculturalism and the cooperation that historically took place between Muslim, Orthodox Christian, Catholic, and Jewish residents. Until the end of World War I (1918) Sarajevo was part of the Austrian Empire. From the interwar period until 1992 it was part of Yugoslavia. Sarajevo became part of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992.

As of 2016 there are approximately 1,000 Jews living in Bosnia, 700 of whom live in Sarajevo; five older members of the community still speak Ladino, the language of the community before World War II. The community center is one of the few Jewish community buildings in Europe that is not protected by security, evidence of the sense of safety felt by Sarajevo's Jewish community within the city. The community center includes an active synagogue, a Sunday school for children ages 3-12, a volunteer-run Jewish newspaper that prints 4-5 issues a year, as well as youth and student groups. Jakob Finci, the former Bosnian ambassador to Switzerland, serves as the president of the Jewish community in Bosnia. Igor Kozemjakin, who returned to Sarajevo after the Bosnian War, helps lead synagogue services. He and his wife, Anna Petruchek, translated a siddur (prayerbook) into Bosnian.

In October, 2015 the Jewish community of Sarajevo marked the 450th anniversary of Jewish life in Bosnia. Events included exhibitions, a two-day international conference, and tours to see the Sarajevo Haggadah.

SARAJEVO HAGGADAH

The Sarajevo Haggadah is perhaps one of the most famous Jewish manuscripts in the world, not only because it is one of the oldest Sephardic Haggadahs in the world, but also for its unlikely survival through some of the worst and most tragic events in Jewish and general history.

The Haggadah is handwritten, and its first 34 pages contain illustrations of major Biblical scenes, from creation through the death of Moses. Historians generally believe that the Sarajevo Haggadah was originally written in Spain, and left the country with Spanish Jews fleeing the Inquisition of 1492. Marginalia indicate that it was in Italy at some point during the 16th century. The Haggadah only reached Sarajevo at the end of the 19th century, when it was sold by Josef Kohen in 1894 to the National Museum of Sarajevo (it is unclear how Kohen came to be in possession of the Haggadah).

During World War II the museum's director, Dr. Jozo Petrovic, and the chief librarian, Dervis Korkut, hid the Sarajevo Haggadah from the Nazis; Korkut, who also saved a Jewish woman during the Holocaust, smuggled the Haggadah out of Sarajevo and gave it to a Muslim cleric in Zenica, who hid it in a mosque.

During the Bosnian War (1992-1995) thieves broke into the museum; the Haggadah was found on the floor, the thieves having discarded it because they believed it was not valuable. During the Siege of Sarajevo (1992-1996) it was stored in an underground vault, though in 1995 the president of Bosnia displayed the Haggadah during the community seder, in order to quell rumors that the Haggadah had been sold in exchange for weapons.

In 2001 the United Nations and the Bosnian Jewish community financed the restoration of the Haggadah and beginning in 2002 it went on permanent display at the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina went bankrupt in 2012, and closed its doors after not being able to pay its employees for over a year. The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art attempted to arrange for the Haggadah to be loaned to them, but due to the complicated politics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the request was denied. The museum was reopened in September 2015 and the Sarajevo Haggadah was put back on display.

HISTORY

The first Jews came to Sarajevo in the middle of the 16th century (the first documented evidence of a Jewish presence dates to 1565). A significant number of Jews who arrived were Spanish refugees from Salonika. In spite of the fact that these new Spanish arrivals spoke a different language (Ladino) and had distinct customs, they were quickly accepted and worked mostly as artisans and merchants. Jews were known as the region's early pharmacists and hatchims (from the Arabic-Turkish word for physician, Hakim). With few exceptions, the Jewish community enjoyed good relations with their Muslim neighbors.

A Jewish Quarter was established in 1577 near the main market of Sarajevo and included a synagogue. Though the general population referred to the Jewish Quarter as the "tchifut-khan," the Jews themselves called it the "mahalla judia" (Jewish quarters) or the "cortijo" (communal yard). As the community grew the Jews began to branch out of the Jewish Quarter, since there were no legal restrictions placed on where Jews could live. Many worked as blacksmiths, tailors, shoemakers, butchers, joiners, and later as metalworkers; they also operated Sarajevo's first sawmill and traded in iron, wood, chemicals, textiles, firs, glass, and dyes.

During the Ottoman period the Jewish community of Sarajevo enjoyed a relatively high standard of living. It had religious and judicial independence and broad autonomy when it came to community affairs. The Ottoman authorities even enforced the sentences imposed by the rabbinical court when they were requested to do so. In exchange, the Jews paid a special tax (kharaj).

The Jewish Quarter, along with the synagogue, was destroyed in 1679 during the Great Turkish War. One of the notable rabbis to serve the community during this period was Rabbi Tzvi Ashkenazi from Ofen (Buda) and known as the Khakham Tzvi. Rabbi Ashkenazi lived in Sarajevo from 1686 until 1697. It was also during this period that new Jewish settlers began arriving from Rumelia, Bulgaria, Serbia, Padua, and Venice. This new wave of immigrants contributed to the community's evolution and growth during the 18th century.

In 1800 there were 1,000 Jews living in Sarajevo.

The community was officially recognized by the Ottoman sultan in the 19th century. Moses Perera was appointed as the rabbi of Sarajevo and as the hakham bashi for Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1840. The Jewish community lived largely in peace and was able to maintain its cultural and religious life. Members expanded their artisan and trade activities, and added copper, zinc, glass, and dyes to their export work. Additionally, by the middle of the 19th century all of Sarajevo and Bosnia's physicians were Jews.

The 1878 annexation of Sarajevo to Austria brought a new wave of Ashkenazi immigrants to the city, who worked as government officials, specialists, and entrepreneurs. They contributed to the country's development and modernization and were pioneers in the fields of optics, watchmaking, fine mechanics, and printing.

A number of Jews were politically active. The first European-educated physician in Bosnia, Isaac Shalom, better known as Isaac effendi, was the first Jewish member to be appointed to the provincial majlis idaret (assembly); he was succeeded by his son Salomon "effendi" Shalom. Javer (Xaver) "effendi" Baruch was elected as a deputy to the Ottoman Parliament in 1876.

By the end of the 19th century there were 10,000 Jews living in Sarajevo.

After World War I, when Sarajevo became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the Jews of Bosnia enjoyed an unprecedented level of freedom and equality. At that point the Jewish population was 14,000, less than 1% of the general population of Bosnia.

Between 1927 and 1931 the Sephardic synagogue, the largest in the Balkans, was built; it would be desecrated and torn down by Croatian fascists and Germans less than ten years later. A theological seminary was opened in 1928 by the Federation of Jewish Communities, and offered a high school education for Jewish students. The seminary's first principal was Rabbi Moritz Levi, who wrote the first history of the Sephardim in Bosnia; he would eventually be killed during the Holocaust.

The Jews of Sarajevo enjoyed a wide range of social and cultural organizations, as well as a thriving Jewish press. La Benevolencia which was founded in 1894, was a major organization that served as a mutual aid society; two of its branches, Melacha and Geula, helped artisans and economic activities. A choir, Lyra-Sociedad de Cantar de los Judios-Espanoles, was established in 1901. La Matatja was the Jewish workers' union. The first Jewish newspaper published in Sarajevo was La Alborada, a literary weekly that appeared from 1898 until 1902. The weekly periodicals Zidovska Svijest, Jevrejska Tribuna, Narodna Tzodovska Svijest, and Jevrejski Glas, the last of which had a Ladino section, were published between 1928 and 1941.

Zionism was also active between the two World Wars. The youth movement Ha-Shomer Ha-Tza'ir was particularly popular; during the Holocaust a relatively high number of its participants, along with participants from the Matatja movement, became partisans, fighters, and leaders of the resistance movement. A Sephardic movement with separatist leanings, associated with the World Sephardi Union, was also active during the interwar period. A number of Jews became involved with the (illegal) Communist Party during the 1930s.

During the interwar period Sarajevo was the third largest Jewish center of Yugoslavia (after Zagreb and Belgrade). In 1935 there were 8,318 Jews living in the city.

Prominent figures from Sarajevo include the writer Isak Samokovlija (d. 1955). Samokovlija vividly described Bosnian Jewish life, particularly the struggles of the porters, peddlers, beggars, and artisans. The artists Daniel Ozmo, who did mostly woodcuts, Daniel Kabiljo-Danilus, and Yosif Levi-Monsino lived in Sarajevo.

THE HOLOCAUST

Sarajevo was captured and occupied by the German Army on April 15, 1941. It was subsequently included in the Independent State of Croatia, an Axis-created Nazi puppet state. That year Sarajevo's Jewish population was 10,500.

On April 16, 1941 the Sephardic synagogue, which was the largest synagogue in the Balkans, was desecrated. This was followed by repeated outbreaks of violence against Sarajevo's Jews, culminating in mass deportations. Between September and November 1941 the majority of the Jewish community of Sarajevo was deported to Croatian concentration camps, including Jasenovac, Loborgrad, and Djakovo, where most were killed. A small number of Jews survived by joining partisan groups or fleeing to Italy.

POSTWAR

A small community was revived after World War II, though most of the survivors immigrated to Israel or other countries between 1948 and 1949. The Ashkenazi synagogue, which had remained relatively intact, became the community center where services were held, and where cultural and social activities were hosted. Rabbi Menahem Romani served as the community's religious leader. A monument dedicated to the fighters and martyrs of the Second World War was erected in the Jewish cemetery in Kosovo.

In 1970 a celebration of the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the Jews in Bosnia and Herzegovina was held in 1970. The community published a memorial book to mark the occasion.

In 1971 there were 1,000 Jews living in Sarajevo.

BOSNIAN WAR

During the Bosnian War (1992-1995), Sarajevo was under siege from April 5, 1992 until February 29, 1996. During the siege 900 Jews were evacuated and taken by bus to Pirovac, near Split, and 150 were flown to Belgrade. Others, including many children, were sent to Israel. Those who remained in Sarajevo were considered neutral in the conflict, allowing them the freedom to organize humanitarian relief through La Benevolencija, which had been reestablished in 1991. La Benevolencija provided food and medicine to the people of Sarajevo, regardless of religion or ethnicity, and operated out of the community center. It also arranged for more than 2,000 people to be evacuated from the besieged city. Because the Jewish cemetery was located on a hill overlooking Sarajevo, it was used by Serbian snipers during the siege and badly damaged.

In 1997 there were 600 Jews in Bosnia and Herzegovina, about half of whom lived in Sarajevo.

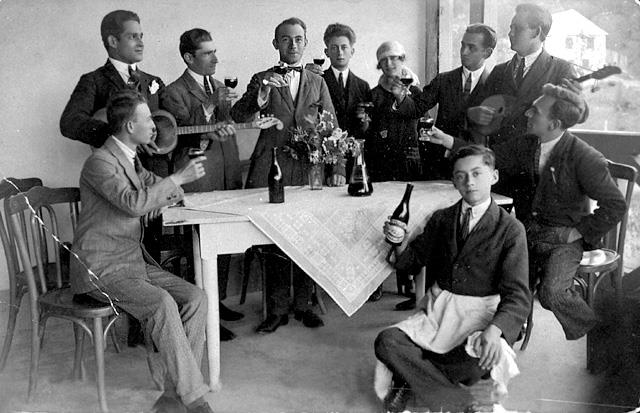

Farewell photo before leaving to go to Israel, Sarajevo, Yugoslavia, 1948-1949

(Photos)Farewell photo before leaving for Israel, Sarajevo, Yugoslavia, 1948-1949.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People, courtesy of the Federation of the Jewish Communities in Yugoslavia.

Interior of the Old Sephardi Synagogue, Sarajevo, Yugoslavia, 1970s

(Photos)the largest in the Balkans, Yugoslavia, 1970s

Thesynagogue was constructed in 1927-1931

After world war II it became a Jewish museum

(The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot,

courtesy of Shlomo Wechsler, Israel)

Children of the Finci and Mandel Families, Sarajevo, 1925

(Photos)Sarajevo, Yugoslavia, 1925.

From Left, Standing: Frieda and Shalom Finci,

Poldi Mandel. Sitting: Ada and Esther Fince,

Erwin and Lili Mandel, Mimi Finci.

(The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot,

Courtesy of Esther Harari, Israel)

Rabbi Judah Alkalai (1798-1878), Sephardi Rabbi born in Sarajevo, and one of the influential precursors of modern Zionism

(Photos)of modern Zionismץ

Born in Sarajevo, he served as the Rabbi of the Sephardi community in Semlin, south Hungary

(The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsots,

courtesy of the Zehavi famliy, Israel)

The young girl Esther Finci in Purim Costume, Sarajevo, Yugoslavia, 1925

(Photos)costume, selling flowers to collect money for the JNF,

Sarajevo, Yugoslavia, 1925

(The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot,

courtesy of Esther Harrari (Finci), Israel)

The Hatanim Ceremony, Sarajevo, Yugoslavia 1948

(Photos)The Hatanim ceremony at the Jewish Community, honoring the elected Hatanim to leave for Israel with the first Aliya in 1948. Sarajevo, Yugoslavia, 1948.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People, courtesy of the Federation of the Jewish Communities of Yugoslavia.