The Jewish Community of Teheran

Teheran

In Farsi: تهران - Alternate spelling: Tehran

Capital of Iran

Situated near the ancient Biblical site of Rages (mentioned in the Book of Tobit, a book that is part of the Catholic and Orthodox Christian canon), Teheran did not rise to prominence until the Kajar dynasty established its capital there around 1788. It soon attracted Jews from a variety provincial villages and towns. According to the Jewish traveler David D'Beth Hillel, the Jewish population in Teheran amounted to about 100 families in 1828.

Travelers, shelichim (emissaries), and other European visitors who came to Teheran throughout the 19th century (including the Christian missionary Joseph Wolff, the explorer Benjamin II (originally Israel Joseph Benjamin), the traveler and writer Ephraim Neumark, and G.K Curzon) pointed to the growth of the Jewish community in Teheran. At first, the Jews lived in a poor quarter ("Mahallah"), where they established synagogues and other religious and social institutions. Nonetheless, they were economically hampered by the fact that they were non-Muslims, with the status of ritually-unclean non-believers (a status shared by Jews and Christians) held by Shi'ite Islam, the religion of the dynasty.

The Jews of Teheran engaged in handicrafts and small businesses, and also worked as itinerant peddlers dealing in carpets, textiles, antiquities, and luxury articles. Very few, however, were able to reach positions of economic importance. Some native Jewish physicians in Teheran in the time of Shah Naser al-Din achieved a measure of prominence, and the Shah eventually appointed an Austrian Jew, Jacob Eduard Polak, as a court physician (Polak was also invited by the government to work as a professor of anatomy and surgery at the military college).

The political and legal status of the Jews improved during the second half of the 19th century, thanks to the intervention of European Jewry on their behalf. During the Shah's visits to Europe in 1873 and 1889, Sir Moses Montefiore and the French lawyer and statesman Isaac Adolphe Cremieux presented him with petitions and demands for better conditions for the Jews of Iran. This intervention led to the establishment of Jewish schools by the Alliance Israelite Universelle; the first Alliance school in Teheran was opened in 1898 with Joseph Cazes as director.

As a result of the constitutional reforms under Shah Muzaffar al-Din in the early decades of the 20th century, the Jews were granted citizenship in 1906, though it would be another few decades until they were permitted to elect their own representative to the Iranian Parliament. Under the Pahlavi Dynasty, especially during the reign of Muhammad Reza Shah (1941-1979), the condition of the Jews throughout Iran improved considerably and the Jews of Teheran enjoyed a level of freedom and equality that they had yet to experience. During this "Golden Age," many Jews rose to influential social and economic positions.

In Teheran the community was served not only by the Alliance, but also by ORT and Otzar HaTorah. Above all, however, the Jewish community in Teheran was supported by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, which in 1947 laid the foundation for all of the social, medical, and educational activities of the Jews of Teheran and Iran as a whole.

A Zionist organization was established in Teheran even before the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and a cultural and spiritual revival also resulted in a considerable degree of Aliyah to Palestine in the early decades of the 20th century. Among Teheran's prominent leaders were Solomon Kohen Tzedek, author of the first Hebrew grammar book for Iranian Jews, Mullah Elijah Haim More, author of three Judeo-Persian books on Jewish tradition and history, Soliman Haim, editor of a Persian Jewish newspaper and an ardent Zionist, Aziz Naim, author of the first history of the Zionist movement in Persian, and Kermanyan, Persian translator of Alex Bein's biography of Theodor Herzl. One of the earliest immigrants to Palestine was Mullah Haim Elijah Elazar whose son, Chanina Mizrachi, wrote several books on Iranian Jews in Palestine and other essays.

There were 35,000 Jews in Teheran in 1948, constituting 37% of the total Jewish population of Iran. Although there was considerable immigration to Israel, Jews from the provinces also migrated to the capital, stabilizing the population numbers. As the country's economic situation improved, so did that of the Jews living there.

Teheran had a network of schools run by the Alliance Israelite Universelle; 15 elementary schools and two high schools, as well as schools run by Otzar HaTorah and ORT. In 1957 it was estimated that about 3,000 Jewish children in Teheran received no education, although this number probably dropped during the 1960s. In 1961 7,100 pupils attended the Alliance Israelite Universelle and Otzar HaTorah. Hundreds of Jews (700-800 in 1949) also studied in Protestant mission schools, and approximately another 2,000 were enrolled in government schools. In 1961 the number of Jewish students at Teheran University was estimated at 300

The community ran the Kanun Kheir Khah Hospital for the Needy (founded in 1958), and a Jewish soup kitchen financed by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. The headquarters of both the youth organization, Kanun Javanan, which extended aid and sponsored lectures to poor children, and of the Jewish women's organization were located in Teheran.

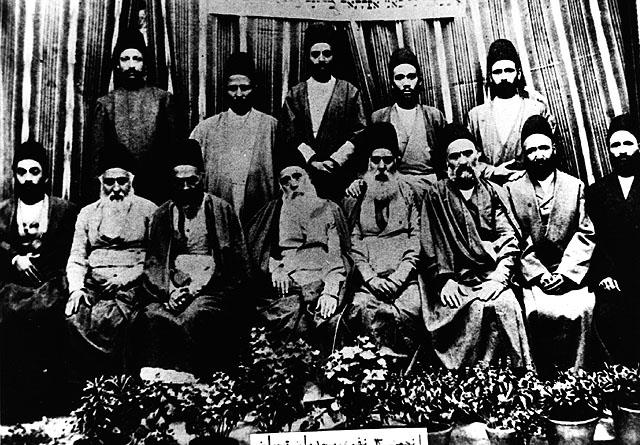

Community affairs were handled by a council led by Ayatollah Montakhab in 1951, and by Arieh Murad in 1959. The head of the rabbinical court in 1959 was Rabbi Yedidiah Shofet. His judge's salary was paid by the government, and his judgments were carried out by government law courts. In 1957 the first Iranian-Jewish Congress was organized in Teheran, and branches of the World Jewish Congress were established.

In 1970 40,000 Jews (55% of the total Jewish population of Iran) lived in Teheran, and the community was composed of Jews from various Iranian provinces, including Meshed, and from Bukhara, Baghdad, and other Middle Eastern communities, as well as of Ashkenazim from Russia, Poland, and Germany.

On the eve of the Islamic Revolution of 1979, there were 80,000 Jews in Iran, concentrated in Teheran (which had the largest Jewish population of approximately 60,000), Shiraz, Kermanshah, and the cities of Kuzistahn. Things shifted rapidly for the Jews of Iran with the Iranian Revolution of 1979. Private wealth was confiscated, and the Muslim population began expressing strong anti-Israel feelings. Zionist activity was made a crime, though the regime officially distinguished between the Jews of Iran, who were considered loyal citizens, and Zionists, Israelis, and world Jewry to whom the regime was hostile.

Nonetheless, the Jews who remained in Iran were living in a sensitive and unpredictable situation that requires constant vigilance. On February 1, 1979 5,000 Jews, led by the chief rabbi, Yedidia Shofet, welcomed the future Supreme Leader of the country, Ayatollah Khomeini with signs proclaiming that "Jews and Muslims are brothers." Three months later, on May 9, 1979, the regime executed Habib Elghanian, a prominent member of the Jewish community in Teheran who served as the president of the Teheran Jewish Society, who was charged with "corruption," "contacts with Israel and Zionism," and "friendship with the enemies of God." Elghanian's execution sent shock waves through the Jewish community, and nearly two-thirds of Iranian Jewry left the country. The gabbai of a Teheran synagogue, 77 year old Faisallah Mechubad, was executed in February, 1994 for supposedly spying for Israel.

In 1996 there were an estimated 25,000 Jews in Teheran (out of 35,000 Jews in Iran as a whole). There were 50 active synagogues, 23 of which were in Teheran, and about 4,000 students enrolled in Jewish schools. Classes in Jewish schools were held in Persian, since teaching Hebrew could lead to problems with the authorities.

Dina Raubnof, Ahvaz, Iran, 2018

(Video)Dina Raubnof was born in Ahvaz, Iran. In this testimony she recounts the history of her family, originally from Isfahan, Iran, her childhood in Tehran, and then her immigration alone, without her parents, as a girl aged 10, and then her life in Israel during the 1950s.

-------------------------

This testimony was produced as part of Seeing the Voices – the Israeli national project for the documentation of the heritage of Jews of Arab lands and Iran. The project was initiated by the Israeli Ministry for Social Equality, in cooperation with The Heritage Wing of the Israeli Ministry of Education, The Yad Ben Zvi Institute, and The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. The film was produced as part of the Seeing the Voices project, 2019

Angella Nazarian recounts her family's escape from Iran, 2012

(Video)International speaker, best-selling author, educator, and psychologist, Angella Nazarian of Los Angeles, CA, was born in Iran and immigrated to Los Angeles at age 11, during the Iranian Revolution. As documented in her memoir, Life As a Visitor, the Iranian Revolution resulted in the separation of her close-kit family members and the community her ancestors had lived in for over 2,000 years.

Angella Nazarian fondly recalls her childhood studying at an international elementary school where she was shielded from the bitter Antisemitism that her father was confronted with. Angella remember getting along wonderfully with a diversity of peers, including fellow Zoroastrians and the Bahai students and friends. Angella remembers the Iranian Jewish community as having high social mobility with some Jewish youth being sent to Europe and the USA for advanced studies. She recalled the duality of traditional values and the embrace of modernity that co-existed within the Jewish community. This was epitomized by her anecdotes regarding her grandmothers. Angella described her maternal grandmother as “old-schooled Iranian woman” because of her traditional mindset, modesty and lack of a formal education. Her paternal grandmother, on the other hand, was a “self-assured, opinionated, modern” woman who lived with openness and vibrancy throughout her life.

During the Iranian Revolution, the country was swept in violent demonstrations and young Angella found it terrifying to hear gun-shots from school yards in her neighborhood. Her always-optimistic father decided to send her, alongside her older sister and her mother, to the United States of American where her two brothers were studying. Without a hint on what how the future would unfold, Angella was excited for a reunion with her siblings in the USA. As the instability in Iran worsened Angella’s father decided to transfer his assets to America and her mother returned to Iran to assist her father.

After the revolution, leaving Iran became illegal and dangerous and Angella’s parents ended up stuck there for five and a half years, while Angella and her siblings waited patiently for them in the USA. Angella’s parents’ passports were confiscated by Iranian authorities and her uncle was accused and jailed for being “Zionist spy.” Miraculously, her uncle was released from jail with the help of a Muslim friend and Angella’s parents found his release as the signal to immediately escape. Like many Jews fleeing Iran after the revolution, Angella’s parents were smuggled to the border of Pakistan with the promise that they would reach to the Hilton Hotel in Karachi, Pakistan and get reimbursed for the heavy fee the smugglers had imposed on them. The promise was not kept and Angella’s parents were left at a motel and hunted down by the Pakistan authorities with the threat of being repatriated to Iran.

Angella’s family in America contacted lawyers from the Jewish Community Federation of Los Angeles and with their help Angella’s parents left Pakistan for France. In France they were briefly detained and upon their release they went to Israel via Portugal. In Israel, they received legal documents from the USA that included valid passports which enabled them to join their family and move to the USA. The family separation over the course of five and a half years and the incredibly challenging journey to the USA have had a tremendous emotional impact on the family and to this day they find it difficult to discuss their journey from Iran to the USA.. In the conclusion of the interview, Angella states how important it is for people to know and embrace their roots and “to honor who they are as they are.” Despite all the hardships, Angella is determine to pass down the “absolutely beautiful tradition, culture, and poetry” of her Iranian heritage to her children.

This film is part of the Testimonies produced by Sarah Levin for JIMENA's Oral History and Digital Experience. JIMENA - Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa - is a San Francisco, CA., based non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of culture and history of the Jews from Arab Lands and Iran, and aims to tell the public about the fate of Jewish refugees from the Middle East.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot, courtesy of JIMENA.

Abraham Berookhim recounts his escape from Iran

(Video)Abraham Berookhim, a resident of Santa Monica, CA., in this testimony from 2013 reflects on the anti-Semitism of the Iranian society and recounts his escape from Iran after the Islamic revolution in 1979.

Abraham Berookhim was born in Tehran, Iran in 1948 to a traditional Jewish family whose records date back to the Babylonian exile. Abraham’s grandfather was educated through Alliance Israelite Universelle and eventually opened a bookstore. Later noticing the lack of translation dictionaries, he financed the publication of three major dictionaries from Farsi to English, Hebrew and French. The dictionaries were used throughout the entire country; the first step in establishing the prominence of the Berookhim family name. Several years later, Abraham’s grandfather went on to open luxury hotels. The hotels were called Sinai and Royal Gardens Hotel to make known its Jewish affiliation; the grand ballroom was donated for Jewish weddings. The Berookhims remained influential and philanthropic within the Jewish community as their notoriety expanded.

Still, despite the Berookhim’s wealth and celebrated family name, Abraham’s memories of childhood in Iran are saturated anti-Semitic discrimination, as some Muslims met his family’s success with resentment. Unfounded rumors against the Jews were normative, and Abraham remembers the common narrative amongst Iran’s mullahs being that the Jews must be either converted or killed.

Abraham personally experienced anti-Semitism regularly. Even at his own family’s hotels, the Muslim kitchen staff sometimes tormented Abraham, insisting that if he intended to inherit the hotel he must first become a Muslim—only then would they agree to eat off his plates. Abraham resigned to lying that he had converted to Islam. It worked; from then Abraham was treated only with kindness. The time leading up to the Iranian revolution and the rise of Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamic Republic ushered an unprecedented degree of anti-Semitism. Abraham was deeply shaken by the capture of his uncle, Ebrahim Berookhim, who was falsely accused of spying on behalf of the United States. In 1979, Abraham’s uncle was executed in prison without a trial. The Berookhims demanded an explanation for his murder, but the Iranian authorities maintained they had meant to capture and kill a different man. However, the Berookhims knew that his execution was meant to send a message to the rest of the Jewish community. The prison guards even requested compensation for the expense of the bullet.

At the hotel one day, Abraham received a call on the hotel telephone. On the other line was a Muslim employee who believed that Abraham had converted to Islam. Abraham recalls the employee pleaded that he flee the hotel for safety. The employees then said that the hotel would hereby belong to the country of Iran, so as to sever all Jewish and Zionist affiliations. Abraham obeyed. Looking back, he realizes that had the employees not thought that he was Muslim, they surely would have let the police capture him. In a way, they saved his life. Abraham was already in hiding by the time of the Iran hostage crisis of late 1979, during which the American Embassy was taken over and six hostages escaped to the Canadian Embassy. Abraham received a call from the U.S. government, who knew of his location through previous hotel dealings. They requested that Abraham provide food and support to the hostages in hiding; Abraham drove to his hotels’ kitchens and filled his car with food, which he personally delivered to the American prisoners.

Abraham’s departure from Iran was complicated as he was forced to leave his wife and newborn son behind, along with every last possession with his bodyguard. Abraham carried only an empty suitcase, a fake Muslim passport and his best Turkish disguise to avoid all ties to his true identity. As soon as the plane crossed Iran’s borders, Abraham shed his disguise and basked in his new freedom.

Abraham spent the first portion of his new life with his Japanese business partner before he moved to Israel without a penny to his name. Four months later, his wife and son joined him. Once in Los Angeles, Abraham slowly rebuilt his life by selling radios and eventually returning to the restaurant industry.

Today, Abraham says he would like to return to Iran in order to visit his bodyguards and friends who had saved his life—and also to visit the hotels he so carefully helped build. It is painful that his family left behind their hard-earned fortune and no compensation nor formal apology for the execution of Abraham’s uncle. But Abraham recognizes he is not alone.

This film is part of the Testimonies produced by Sarah Levin for JIMENA's Oral History and Digital Experience. JIMENA - Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa - is a San Francisco, CA., based non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of culture and history of the Jews from Arab Lands and Iran, and aims to tell the public about the fate of Jewish refugees from the Middle East.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, Beit Hatfutsot, courtesy of JIMENA

Jacqueline Hakak Mostafi Describes Her Life in Teheran, Iran, Before the Islamic Revolution, 2018

(Video)Jacqueline Hakak Mostafi was born in Iran. She immigrated to Israel about two weeks after the start of the Islamic revolution. Her parents remained in Iran. She recalls the feelings of the local residents before the revolution. They lived near the university in Tehran, and she saw with their own eyes how the police and the army treated the young people who decided to rebel against the government. She tells of a feeling of fear and terror, of shots fired indiscriminately, of people running into their building, and how they helped them to hide. Like many other immigrants from Iran, she describes the place as heaven on earth. Jews had a good life and she maintains contact with her Muslim friends to this day. On the other hand, she also has unpleasant stories about this relationship with Muslim women with whom she studied. Once on her birthday she received balloons as a gift from her parents, and she wanted to show them to her best friend. She arrived at her house and the friend's mother threw her out of the house and took the balloons from her. Since then she stopped going to visit her Muslim friends.

-------------------------

This testimony was produced as part of Seeing the Voices – the Israeli national project for the documentation of the heritage of Jews of Arab lands and Iran. The project was initiated by the Israeli Ministry for Social Equality, in cooperation with The Heritage Wing of the Israeli Ministry of Education, The Yad Ben Zvi Institute, and The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. The film was produced as part of the Seeing the Voices project, 2019

Morris Nemika Recalls His Childhood in Teheran, Iran, and His Immigration to Israel, 2018

(Video)Morris Nemika was born in Teheran, Iran, in 1968 and immigrated to Israel in 1986. In this testimony he recounts his childhood in Iran, tells about his family, their relations with the Muslim population, and their immigration to Israel.

-------------------------

This testimony was produced as part of Seeing the Voices – the Israeli national project for the documentation of the heritage of Jews of Arab lands and Iran. The project was initiated by the Israeli Ministry for Social Equality, in cooperation with The Heritage Wing of the Israeli Ministry of Education, The Yad Ben Zvi Institute, and The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. The film was produced as part of the Seeing the Voices project, 2019

Esther Adika Recalls Her Life in Teheran, Iran, and in Israel, 2018

(Video)Esther Adika was born in Ahvaz, Iran, and grew up in Teheran, Iran, and immigrated to Israel in 1951. In this testimony she recalls her family's life in Iran and her experience in Israel.

-------------------------

This testimony was produced as part of Seeing the Voices – the Israeli national project for the documentation of the heritage of Jews of Arab lands and Iran. The project was initiated by the Israeli Ministry for Social Equality, in cooperation with The Heritage Wing of the Israeli Ministry of Education, The Yad Ben Zvi Institute, and The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. The film was produced as part of the Seeing the Voices project, 2019

Shoshana Rotem Recounts Her Immigration From Teheran, Iran, and Her Life in Israel, 2018

(Video)Shoshana Rotem was born in Teheran, Iran in 1941. Her father was a traveling merchant, and her mother was at home, and together they raised six children. The life of the Jewish girls in Teheran was a life full of fear. The girls were not allowed to leave the house without an escort, and even more so at night. The fear was that someone would kidnap or rape them. Shoshana went to the "Alliance" school, but she remembers that even there the attitude was discriminatory and difficult. When she was about 8 years old and her older sister was 10 years old, their father and mother woke them up one night and sent them to Israel as part of Aliyat Hanoar (Youth Aliyah). They arrived at the airport in Teheran, where the Youth Aliyah members asked one of the passengers to watch over them during the flight. Shoshana was afraid of the plane, and looked for father and mother. Her sister explained to her that they were on their way to Israel, and that their parents remained in Iran, and they were alone from now on. In Israel, Shoshana moved from one boarding school to another, according to age and situation, and these boarding schools and their dedicated staff members were a home and a family for her. When she finished high school, she began studying to be a nurse, and later joined the IDF. Shoshana was on the medical team that established Soroka Hospital in Beer Sheva, and there she also met her future husband. When her eldest son was six months old, her parents and her brother immigrated to Israel, and so she could help them in their old age.

-------------------------

This testimony was produced as part of Seeing the Voices – the Israeli national project for the documentation of the heritage of Jews of Arab lands and Iran. The project was initiated by the Israeli Ministry for Social Equality, in cooperation with The Heritage Wing of the Israeli Ministry of Education, The Yad Ben Zvi Institute, and The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. The film was produced as part of the Seeing the Voices project, 2019

Shlomo Cohen of Amara, Iraq, 2018

(Video)Shlomo Cohen was born in Amara, Iraq, in 1929. In this testimony he recalls his life in Iraq. His father, Nissim, was a tailor and his mother, Miriam (Miry), helped him. Shlomo has three daughters and a son who help him. He had many brothers and sisters. He remembers the Farhud, when he hid with his parents in a kind of basement. They arrived by plane at Sha'ar Aliyah Transit Camp for New Immigrants near Haifa. From there they went to the village of Yavne. Shlomo studied at the Teachers' Seminary. Life was difficult, but overall they felt good in Israel.

-------------------------

This testimony was produced as part of Seeing the Voices – the Israeli national project for the documentation of the heritage of Jews of Arab lands and Iran. The project was initiated by the Israeli Ministry for Social Equality, in cooperation with The Heritage Wing of the Israeli Ministry of Education, The Yad Ben Zvi Institute, and The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The Oster Visual Documentation Center, ANU - Museum of the Jewish People. The film was produced as part of the Seeing the Voices project, 2019