The Jewish Community of Hamburg

A major port city and state in Germany. Since 1937 it has included the towns of Altona and Wandsbeck.

In 2004 there were approximately 3,000 Jews living in Hamburg. There was one synagogue, the Hohe Weide Synagogue, one kindergarten, the Ronald Lauder Jewish Kindergarten, and kosher food was sold by one man, Shlomo Almagor, a native of Israel.

HISTORY

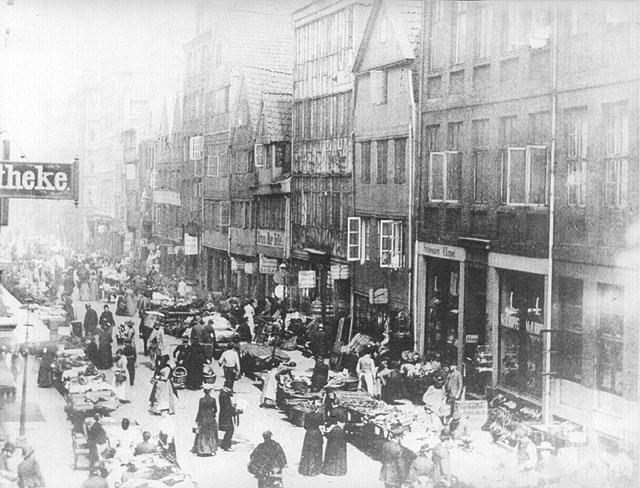

Jews have lived in Hamburg since the end of the 16th century, when wealthy Marranos from Spain and Portugal arrived in the city via the Netherlands. They unsuccessfully attempted to observe Jewish customs and rituals; when they were discovered, some of the Christian residents of the city demanded their expulsion. However, the city council opposed the measure, pointing out the community's economic contributions. German Jews began to be admitted to Wandsbeck by 1600, and in 1611 some of them settled in Altona, both of which were under Danish rule. By 1627 German Jews began to settle in Hamburg itself, although on festivals they continued to travel to Altona in order to worship, since in 1641 the Danish king had permitted the official establishment of a congregation and the building of a synagogue there. The rabbi of the Altona congregation was also responsible for mediating any disputes that arose within the congregation.

The Jews of Hamburg worked as financiers, and some helped found the Bank of Hamburg in 1619. Other Jewish residents of the city worked as shipbuilders, importers (particularly of sugar, coffee, and tobacco from the Spanish and Portuguese colonies), weavers, and goldsmiths. Their taxes were high; in 1612 the Jews of Hamburg paid an annual tax of 1,000 marks, a sum which had doubled by 1617.

The original Jewish community of Hamburg continued to maintain ties to their countries of origin. The kingdoms of Sweden, Poland, and Portugal appointed Jews as their ambassadors to Hamburg. Those who had come to Hamburg from Spain and Portugal continued to speak the languages of their native lands for two centuries. There were about 15 books printed in Hamburg in Portuguese and Spanish from 1618 to 1756, which was a major development in Jewish printing in the city; from 1586 Hebrew books, especially the Bible, had been published in Hamburg by Christian printers, often with the help of Jewish employees.

As early as 1611 Hamburg had enough of a Jewish community for three Sephardic synagogues, whose congregations jointly owned burial grounds in nearby Altona. In 1652 the three congregations combined under the name of Beth Israel.

The philosopher Uriel da Costa, who wrote the controversial book, "An Examination of the Traditions of the Pharisees," fled to Hamburg from Amsterdam in 1616 after his excommunication for blasphemy. The community, however, did not accept him (the fact that he did not understand German was an additional difficulty). The local physician Samuel da Silva wrote a pamphlet attacking him and his excommunication was announced publicly in the Hamburg synagogue. Da Costa returned to Amsterdam after one year.

Many Jews, fleeing from persecution in Ukraine and Poland, in 1648 arrived in Hamburg in 1648, and were helped by the local Jews. However, these refugees soon left for Amsterdam since tensions with the Christian community were rising, culminating in the expulsion of the Ashkenazi community in 1649. Most of those who were expelled left for Altona and Wandsbeck; only a few remained in Hamburg, residing in the homes of the Spanish-Portuguese Jews in order to obtain legal status in the city.

The expulsion proved to be temporary; after a few years, many of those who had been driven out returned to Hamburg. In 1656 a number of refugees from Vilna also arrived, adding to the Jewish presence in the city. The three Ashkenazi congregations, Altona, Hamburg, and Wandsbeck, united in 1671 to form the AHW Congregation; the community's rabbinical headquarters were in Altona. One of the most famous rabbis of the merged congregation was Jonathan Eybeschuetz, who was appointed to the post in 1750. His equally famous adversary, Jacob Emden, lived in Altona. The congregation ceased to exist in 1811 when the French authorities imposed a single consistorial organization on the city; at that point, the Ashkenazim and Sephardim united to form one congregation. The Altona community retained its own rabbinate, which was also recognized by the Jews of Wandsbeck until 1864.

Sabbateanism swept the community in 1666; the community's governing body even announced that the community buildings were for sale, in anticipation of the imminent arrival of the Messiah. Rabbi Jacob B. Aaron Sasportas was one of the few who was not swept up into the enthusiasm and he became a fierce opponent of the Sabbateans.

In 1697 the city unexpectedly raised the annual tax levied against the Jews to 6,000 marks. Consequently, the majority of the wealthy Jews of Hamburg moved to Altona and Amsterdam.

The Reform movement, which began in Berlin, eventually reached Hamburg. A Reform temple was dedicated in 1811, and in 1819 a new prayerbook was published that better suited the needs of the new congregation. The Reform community of Hamburg, however, faced extreme opposition from the other rabbis in the community. The rabbinate in Hamburg published the opinions of noted Jewish scholars that sought to discredit the temple, and they prohibited the use of its prayerbook. During Rabbi Isaac Bernays' term leading the community (1821-1849), controversy flared again when the Reform congregation built a new synagogue building and published a more radically abridged and revised version of the prayerbook, "Siddur HaTefillah," in 1844. Rabbi Bernays, for his part, was a proponent of Modern Orthodoxy, and sought to endow the traditional service with greater beauty; he also modernized the curriculum of the local Talmud Torah and regularly gave sermons in German. Rabbi Jacob Ettlinger, a fierce opponent of Reform Judaism, founded an anti-Reform journal around the same time.

Other German Jews of note who lived in Hamburg included Glueckel of Hameln, the merchant and philanthropist Salomon Heine (the uncle of Heinrich Heine), Moses Mendelssohn (as well as Rabbi Raphael Kohen who was fiercely opposed to Mendelssohn's translation of the Pentateuch into German), the poets Naphtali Herz Wessely and Shalom B. Jacob HaCohen, the author of Dorot HaRishonim Isaac Halevy, the art historian Aby Warburg, the philosopher Ernst Cassirer, the psychologist William Stern, the shipping magnate Albert Ballin, and the financiers Max Warburg and Karl Melchior. The municipal library and the library of the University of Hamburg contained a large number of Hebrew manuscripts. Nearly 400 Hebrew books were printed in Hamburg between the 17th and 19th centuries; during the 19th century, Jewish printers mostly issued prayer books, the Pentatuch, books on mysticism, and popular literature.

The Jewish congregation of Hamburg became the fourth largest community in Germany. In 1866 there were 12,550 Jews in Hamburg; by 1933 that number had risen to 19,900 (1.7% of the total population), including more than 2,000 who lived in Altona. The last rabbi of the community before World War II was Joseph Carlebach (the father of Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach and Professor Miriam Gillis-Carlebach) who was deported in 1942 and killed by the Nazis.

Between 1933 and 1937, after the Nazi party came to power in Germany, more than 5,000 Jews from Hamburg emigrated to other countries; another 1,000 Polish citizens were expelled on October 28, 1938. Shortly thereafter, on the night of November 9, 1938, there was a pogrom that came to be known as Kristallnacht. Most synagogues were looted and vandalized. This led to another surge of Jews leaving Germany. A deportation took place in 1941, when 3,148 Jews were deported to Riga, Lodz, and Minsk. 1,848 Jews were deported to Auschwitz and Theresienstadt in 1942. Between 1941 and 1945 there were 17 transports of Jews from Hamburg to Lodz, Minsk, Riga, Auschwitz, and Theresienstadt. By 1943 there were 1,800 Jews left in Hamburg, most of whom were married to non-Jews; the official liquidation came in June of that year.

Approximately 7,800 Jews from Hamburg were killed during the Nazi era, including 153 who were mentally ill and executed, and 308 who committed suicide. During this period the community was led by Max Plaut and Leo Lippmann (who committed suicide in 1943). A concentration camp, Neuengamme, was located near the city; a total of 106,000 inmates passed through its gates, more than half of whom were killed.

On May 3, 1945 Hamburg was liberated by British troops, who offered aid to the few hundred Jewish survivors. On September 18, a Jewish community was organized and managed to reopen the cemetery, old age home, mikvah, and hospital. By March 18, 1947 the community numbered 1,268, its numbers fluctuating due to emigration, immigration, and a high mortality rate.

In 1960 a hospital with 190 beds was opened, and a large modern synagogue was consecrated. Herbert Weichmann was elected Buergermeister in 1965 and the Institute for Jewish History was founded in 1966, which worked to promote Jewish-Christian understanding. During the sixties a number of Jews arrived from Iran, sent by the shah in order to import Persian carpets.

In January 1970 there were 1,532 Jews in Hamburg, two-thirds of whom were above 40 years old. Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union began arriving in the 1990s.

Lotte Leonard

(Personality)Lotte Leonard (1884-1976), soprano, born in Hamburg, Germany. She studied in Berlin and specialized in singing lieder and oratorios. Leonard sang as soloist with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra Choir and at the German Bach and Handel Festivals. She fled Nazi Germany in 1933 and became professor of singing at the International Conservatory in Paris.

Later she continued her teaching career in the United States.

Jacob Blumenthal

(Personality)Jacob Blumenthal (1829-1908), pianist and composer, born in Hamburg, Germany, he left for England in 1848 and became court pianist to Queen Victoria. Blumenthal composed many piano pieces in the fashionable style of the era. He gained his fame as composer of some sentimental popular songs, including The Days That Are No More and Come Not, When I Am Dead set to words by Alfred Tennyson. He died in London, England

Paul Aron Sandfort

(Personality)Paul Aron Sandfort (1930-2008) Writer and composer. Born as Paul Rabinowitsch in Hamburg, Germany, he immigrated in 1936 to Copenhagen. His parents were of Jewish-Russian origin. His father perished in Auschwitz in 1943, and in honor of him Rabinowitsch has taken the name Aron as a pseudonym for his Danish, English, Italian and German publications. In his childhood he learnt to play the piano and the trumpet entering the Tivoli Boys' Guard orchestra in Copenhagen. In October 1943 he was deported to Terezin where he played the trumpet in the orchestra which took part in performances of the childrens' opera "Brundibar" by Hans Krasa. Sadfort also played at a performance in honor of the visit of the Red Cross commission in June 1944. He also played the trumpet in the propaganda film called "Hitler presents the Jews with a City". A few weeks before the end of the war in 1945 he was liberated by the Danish Red-Cross and returned to Denmark.

After the war he studied musicology and German literature. From 1962-64 he became an assistant stage director at the Rome Opera House, subsequently teaching musicology and literature at high schools and conservatories in Denmark.In 1972 he changed his surname to Sandfort and has been stage director at performances of the children's opera ‘Brundibar’ throughout Europe. He has written an autobiographic novel "Ben" and has translated the libretto of "Brundibar" into Danish. Paul Aron Sandfort compiled and wrote the overture to "Brundibar" early in 2005. It consists of a number of themes from the opera connected together and is designed to be played as a prelude, running straight into the action without a break. Hans Krasa adapted the scoring for the available instrumentalists in Terezin and it is this scoring which Sandfort uses in the overture ( 4 violins, cello, flute, clarinets, trumpet , piano , guitar and accordion).

He died in Denmark.

Paul Dessau

(Personality)Paul Dessau 1894-1979), composer and conductor, born in Hamburg, Germany. He studied in Berlin and then conducted and coached opera groups in several cities - Koln, Mainz and Berlin, between 1919-1933. In 1933 Dessau emigrated to Paris and from 1939 lived in New York and Hollywood, where his collaboration with Bertolt Brecht began. In 1948 he returned to Germany and settled in East Berlin.

Dessau composed vocal music notably to texts by Bertolt Brecht, ranging from songs to cantatas and operas (Die Verurteilung des Lukullus, 1951/68, Puntilla, 1966). He also wrote functional music for radio and theater (Furcht und Elend des Dritten Reiches, 1938, Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder, 1946, Der gute Mensch von Sezuan, 1947, Herr Puntilla und sein Knecht MattI, 1949, Der Kaukas Kreidekreis, 1954), as well as, since 1935, music influenced by the 12-tone technique. Among Dessau’s other works are the operas Lanzelot(1969), Einstein (1974) and Leonce und Lena (1978), operas for children, the oratorio Haggadah Shel Pessah (1934), the cantata Requiem For Lumumba (1963), Bach Variations for orchestra (1963), Sonatina for piano (1955), Seven Movements for string quartet (1974), and Music for 15 string instruments (1979). He died in East Berlin, East Germany.

Glueckel of Hameln

(Personality)When she was aged 14, Glueckel was taken by her parents to the small town of Hameln, near Hanover, to be married to Chaim Segal Goldschmidt, a merchant a few years older than her. The couple lived in Hameln for a year and then moved to Hamburg, where they rented the house that Glueckel would live in until 1700. The couple would enjoy thirty years of happy marriage and fruitful partnership, build considerable wealth, raise twelve children, and arrange for them marriages of wealth and prestige. Glueckel and Chaim worked together running his business trading gold, silver, pearls, jewels, and money. Chaim travelled to England and Russia and throughout Europe selling his goods, with Glueckel advising him on his business dealings, drawing up partnership contracts, and helping keep accounts. As her older children grew up, Glueckel also became involved in arranging their marriages. This meant travel in Germany and abroad, and a fuller understanding of business affairs.

One evening in 1688 while travelling to a business appointment, Chaim fell on a sharp rock. He died several days later. Glueckel found herself responsible for her husband's business as well as for the future of her eight unmarried children. Demonstrating excellent business acumen and a sensible desire to stabilise her financial situation, Glueckel auctioned some of her husband's possessions, paid off his creditors and kept a significant amount for herself and the eight children still living at home. Then she slowly resumed Chaim's trade of pearls. When she saw that the business was successful she expanded it by opening a store. She then started to manufacture and sell stockings, the business began to sell imported and local goods and she began to lend money. She arranged the marriages of all but her youngest child. While expressing a desire to spend her last years in the Land of Israel, she opted instead for security. Her daughter Esther had married Moyse Abraham Schwabe, who lived in the French-controlled city of Metz. At her recommendation, Glueckel moved to Metz and at the age of 54 reluctantly agreed to marry widower Cerf Hertz Levy, a merchant who was wealthier than Chaim had ever been. Levy had seemed an attractive enough prospect: a wealthy businessman and community leader in Metz. Unfortunately, within two years the merchant was bankrupt, losing not only his money but Glueckel's as well. For ten years the merchant tried to recoup his losses, but never successfully. In 1712, Glueckel was again widowed, but this time she was 66 and in poor health. For three years she lived alone in Metz. Finally, she moved in with daughter Esther and stayed there until her death.

In 1690 shortly after Chaim's death, Glueckel began to write her memoirs. The opening words of the memoirs were “In my great grief and for my heart's ease I begin this book the year of Creation 5451 [1690-91] — God soon rejoice us and send us His redeemer! I began writing it, dear children, upon the death of your good father, in the hope of distracting my soul from the burdens laid upon it, and the bitter thought that we have lost our faithful shepherd. In this way I have managed to live through many wakeful nights, and springing from my bed shortened the sleepless hours.” Clearly she considered the memoirs a kind of therapy after her husband's death, and she wished to tell her children (and their children) about her husband, herself, and their families, but she could not possibly have foreseen that they would comprise one of the most remarkable documents of the late 17th and early 18th century. Her memoirs, which describe her life as mother of fourteen children and as businesswoman and trader, has given scholars, students and laymen an invaluable document about Jewish life in Europe in the 17th century. The first five books of the work were apparently completed before her second marriage: she was sad at the loss of her beloved Chaim, but proud of her success at business and marriage arrangements and proud of her children (most of the time). The last two books were written after 1712, when she was again alone and much sadder. Glueckel's story, however, ends happily. She wrote that although she had obviously been loathe to give up her independence and to rely on her children, she willingly agreed to move in with her daughter Esther and son-in-law Moyse in Metz. The memoirs clearly show that as she watched a her children and grandchildren continue to marry well, have children, and prosper Glueckel lived out her remaining years in the shelter of her daughter and son-in-law's evident warm love and respect. As Glueckel put it, she was "paid all of the honors in the world." Most of the narrative ends in 1715, although a few anecdotes continue to 1719.

The original Yiddish manuscript of Glueckel's book is lost, but copies were made by one of her sons and by a great-nephew, and from these her work was published in 1896 as "Zikhroynes Glikl Hamel".

Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy

(Personality)Felix Mendelson Bartholdy (1809-1947), composer, conductor, pianist, born in Hamburg, Germany, the son of Abraham Mendelssohn, a banker and a patron of the arts, and the grandson of Moses Mendelsohn, a philosopher of the Enlightenment. Recognized as a musical prodigy, he received a thorough education in both music and the humanities under the guidance of his parents, who engaged some of the finest music teachers and composers of the time to further his musical education. He began composing music at the age of nine and continued to produce remarkable works throughout his life. In 1816, his family moved to Berlin, where Mendelssohn continued his musical studies. He was introduced to some of the leading musicians of the time, among them Carl Friedrich Zelter and Ludwig Berger, who played a central role in shaping his musical development. Zelter, in particular, was a mentor and close friend, providing Mendelssohn with invaluable guidance and introducing him to the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, which would become a lifelong passion.

Mendelssohn's early compositions displayed a maturity and sophistication that belied his age. At the age of 17, he composed his famous overture to Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, a work that remains one of his most enduring and popular compositions and that firmly established him as a prominent composer in Europe.

Mendelssohn continued to develop his career as a musician and composer. He travelled extensively across Europe, including to Paris, London, and other major European cities, showcasing his prodigious talent as a pianist and conductor. His encounters with contemporary composers, among them Franz Liszt, Hector Berlioz, and Niccolò Paganini further enriched his musical experiences and broadened his horizons.

Mendelssohn's music drew inspiration from the works of Bach and Handel, reviving their music at a time when it had fallen into relative obscurity. His oratorio, "Elijah," is a testament to his deep admiration for Handel's music and his ability to infuse new life into the oratorio tradition. Other notable works include his Italian Symphony, Scottish Symphony, and his Violin Concerto in E minor, which remains a staple of the violin repertoire. Mendelssohn's contributions to music were not limited to composition. He also played a significant role in reviving interest in the music of Bach, conducting performances of Bach's St. Matthew Passion that led to a revival of curiosity in Baroque music. His position as the conductor of the Gewandhaus Orchestra in Leipzig solidified his reputation as a respected conductor.

Felix Mendelssohn died a few months after the passing of his sister, the pianist and composer Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel (1805-1847). The siblings maintained a close relationship throughout their lives with Fanny serving as Felix's confidant and counselor.

Otto Jaffe

(Personality)Otto Jaffe (1846-1929) Sir and industrialist. Born in Hamburg, Germany, he was taken as a child to Belfast, Ireland, where his father had founded the Jewish community and established a linen business. Otto Jaffe was in New York from 1865 to 1877 and then assumed direction of the family firm, which he made into one of the main industrial concerns in Northern Ireland and the largest linen exporter to Europe. Jaffe was Lord Mayor of Belfast in 1899 and 1904 and High Sheriff in 1901. He headed the Jewish community and made many benefactions to the city. However when World War 1 broke out he became the object of widespread hostility because of his German origin and moved with his family to England.

Abraham Hezekiah Bassan

(Personality)Abraham Hezekiah Bassan (18th-19th centurie), poet, born in Hamburg, Germany, where his father served as rabbi of the Spanish and Portuguese community. Between 1735-1756 he lived in Amsterdam and was employed as proofreader for the Hebrew press in the city. In 1755 he published an order of service for a fast day announced following the earthquake in Lisbon. In 1773 he moved to Hamburg and succeeded his father.

Abraham Bassan contributed an introduction and a 13-stanza poem to Benjamin Raphael Dias Brandon’s Orot ha-Mizvot (1753). Some of his other poems were also published in works of other authors, among them David Franco-Mendes, Raphael Ben Gabriel Norzi and Mordecai Ben Isaac Tamah. Bassan also wrote a book of eulogies Sermones Funebres (Amsterdam, 1753). He died in Hamburg, Germany.

Samson Raphael Hirsch

(Personality)Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808-1888), rabbi and religious thinker, born in Hamburg, Germany. In 1830 he became Chief Rabbi of Oldenburg where he wrote his classic works Nineteen letters on Judaism and Horeb in which he first expounded his theological system. In 1841 he became Rabbi of Aurich and Osnabrueck and from 1846 to 1851 lived in Nikolsburg (now Mikulov, Czech Republic) as Chief Rabbi of Moravia. Despite his Orthodoxy, his modern innovations caused a rift with the extreme Orthodox community and he moved to Frankfurt on Main. There he organized an autonomous Orthodox community (separate from the Reform who dominated Frankfurt Jewry) and this became the model for other separatist Orthodox communities throughout Germany. In 1876 he obtained official legislation that gave legal recognition to these Orthodox communities. Hirsch was the founder of Neo-Orthodoxy whose motto was 'Torah with secular knowledge', which became the forerunner of modern Orthodoxy.

While remaining Orthodox, he advocated modernization within its framework. He created a network of schools in this spirit and translated key works of Jewish tradition into German, providing them with commentaries that proved highly influential.

Manfred Lewandowski

(Personality)Manfred Lewandowski (1895-1970), cantor., born in Hamburg, Germany. He studied with Yossele Rosenblatt and became famous as a cantor in Berlin. He made many recordings, some of which were later destroyed by the Nazis. In 1938 he left Germany, going first to Paris and then, in 1939, to the United States. He was the great-nephew of composer Louis Lewandowski. He died in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.